New Laser Experiment Spins Light Like a Merry-go-round

- Details

- Category: Research News

- Published: Wednesday, February 28 2024 05:33

In day-to-day life, light seems intangible. We walk through it and create and extinguish it with the flip of a switch. But, like matter, light actually carries a little punch—it has momentum. Light constantly nudges things and can even be used to push spacecraft. Light can also spin objects if it carries orbital angular momentum (OAM)—the property associated with a rotating object’s tendency to keep spinning.

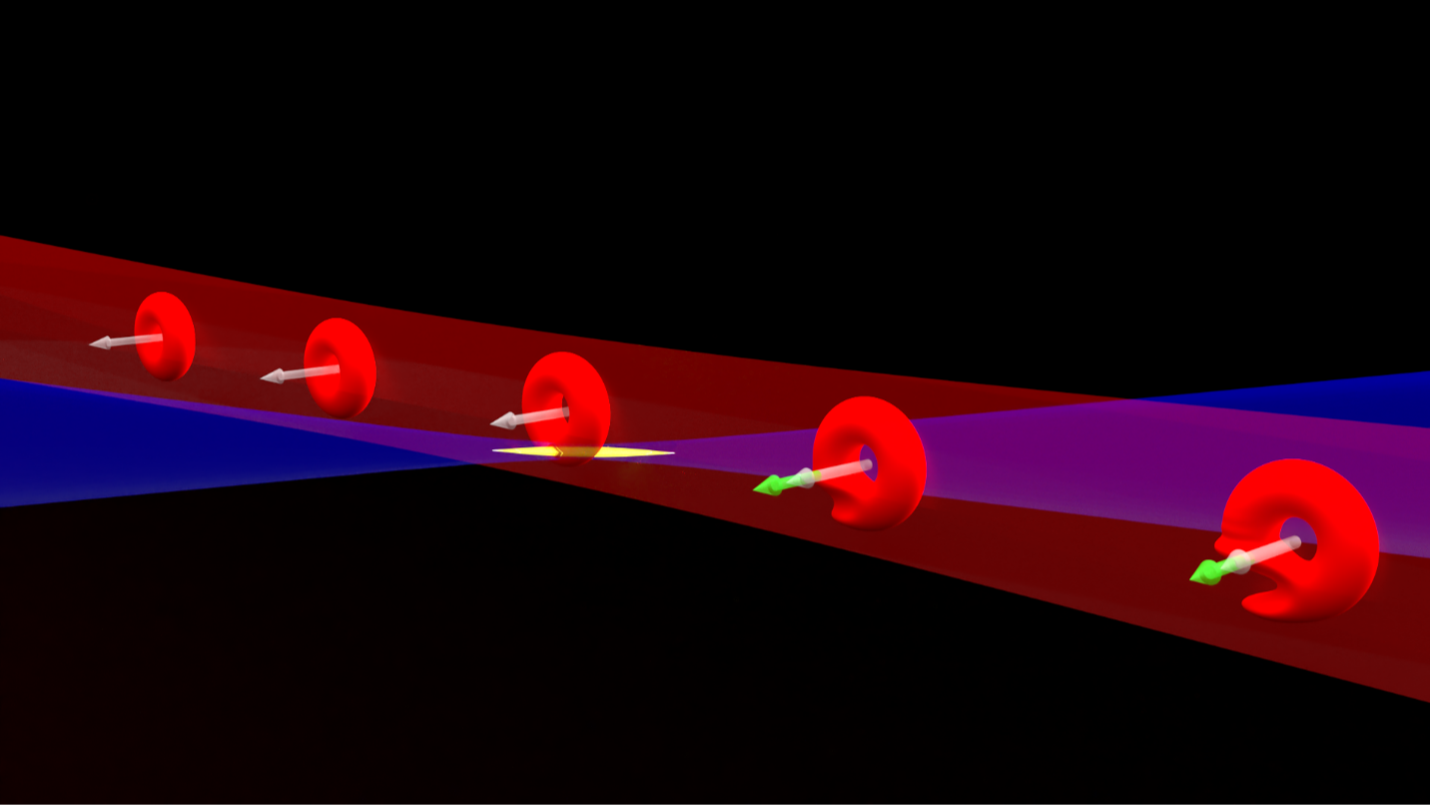

Scientists have known that light can have OAM since the early 90s, and they’ve discovered that the OAM of light is associated with swirls or vortices in the light’s phase—the position of the peaks or troughs of the electromagnetic waves that make up the light. Initially, research on OAM focused on vortices that exist in the cross section of a light beam—the phase turning like the propeller of a plane flying along the light’s path. But in recent years, physicists at UMD, led by UMD Physics Professor Howard Milchberg, have discovered that light can carry its OAM in a vortex turned to the side—the phase spins like a wheel on a car, rolling along with the light. The researchers called these light structures spatio-temporal optical vortices (STOVs) and described the momentum they carry as transverse OAM.

“Before our experiments, it wasn’t appreciated that particles of light—photons—could have sideways-pointing OAM,” Milchberg says. “Colleagues initially thought it was weird or wrong. Now research on STOVs is rapidly growing worldwide, with possible applications in areas such as optical communications, nonlinear optics, and exotic forms of microscopy.”

In an article published on Feb. 28, 2024, in the journal Physical Review X, the team describes a novel technique they used to change the transverse OAM of a light pulse as it travels. Their method requires some laboratory tools, like specialized lasers, but in many ways, it resembles spinning a playground merry-go-round or twisting a wrench. Similarities exist between spinning everyday items, like a playground merry-go-round, and spinning vortices of light. Image credit: Martin Vorel

Similarities exist between spinning everyday items, like a playground merry-go-round, and spinning vortices of light. Image credit: Martin Vorel

“Because STOVs are a new field, our main goal is gaining a fundamental understanding of how they work. And one of the best ways to do that is to mess with them,” says Scott Hancock, a UMD physics postdoctoral researcher and first author of the paper. “Basically, what are the physics rules for changing the transverse OAM of a light pulse?”

In previous work, Milchberg, Hancock and colleagues described how they created and observed pulses of light that carry transverse OAM, and in a paper published in Physical Review Letters in 2021, they presented a theory that describes how to calculate this OAM and provides a roadmap for changing a STOV’s transverse OAM.

The consequences described in the team’s theory aren’t so different from the physics at play when kids are on a playground. When you spin a merry-go-round you change the angular momentum by pushing it, and the effectiveness of a push depends on where you apply the force—you get nothing from pushing inwards on the axle and the greatest change from pushing sideways on the outer edge. The mass of the merry-go-round and everything on it also impact the angular momentum. For instance, kids jumping off a moving merry-go-round carry away some of the angular momentum, making the merry-go-round easier to stop.

The team’s theory of the transverse OAM of light looks very similar to the physics governing the spin of a merry-go-round. However, their merry-go-round is a disk made of light energy laid out in one dimension of space and another of time instead of two spatial dimensions, and its axis is moving at the speed of light. Their theory predicts that pushing on different parts of a merry-go-round light pulse can change its transverse OAM by different amounts and that if a bit of light is scattered off a speck of dust and leaves the pulse then the pulse loses some transverse OAM with it.

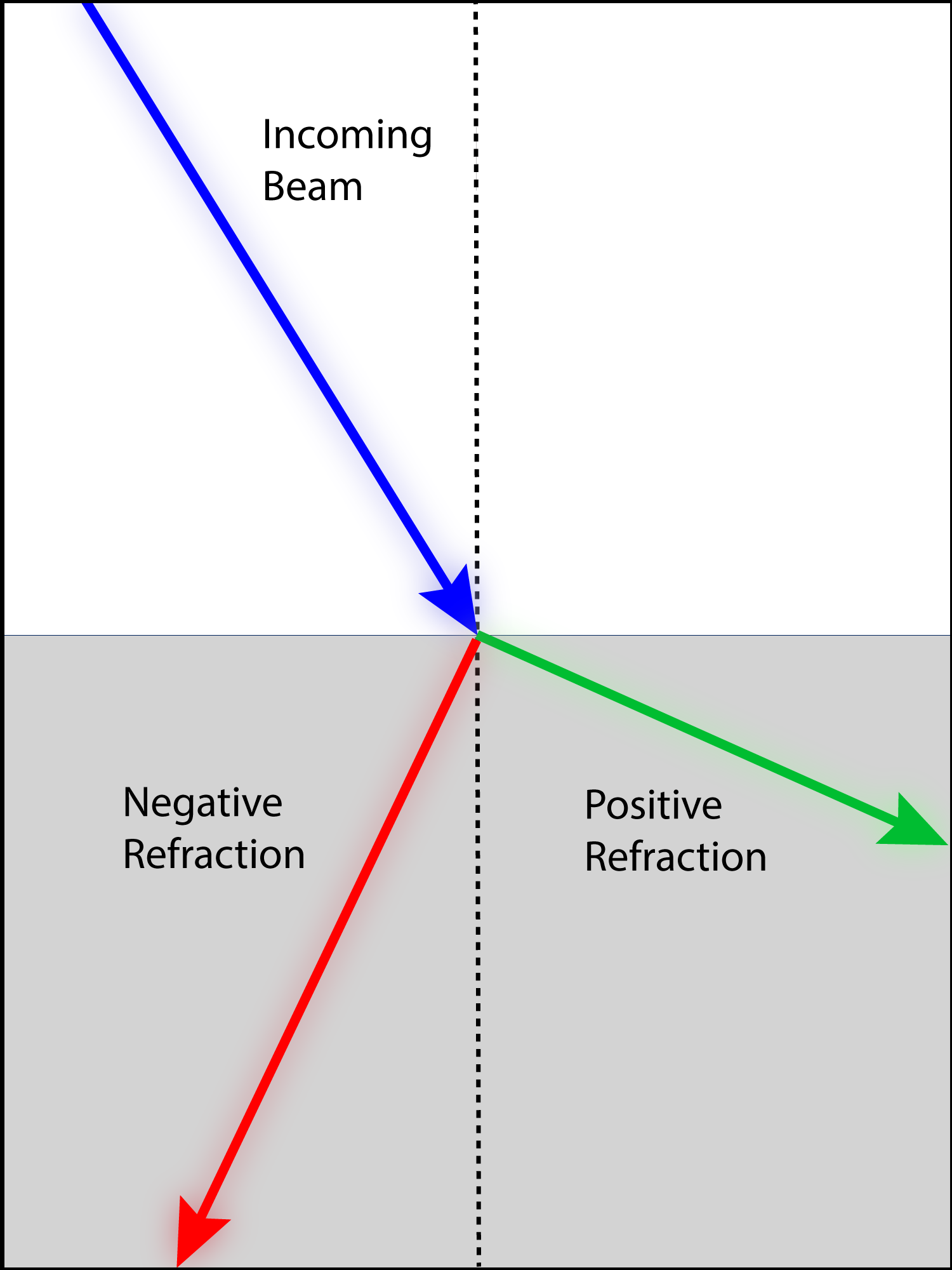

The team focused on testing what happened when they gave the transverse OAM vortices a shove. But changing the transverse OAM of a light pulse isn’t as easy as giving a merry-go-round a solid push; there isn’t any matter to grab onto and apply a force. To change the transverse OAM of a light pulse, you need to flick its phase.

As light journeys through space, its phase naturally shifts, and how fast the phase changes depends on the index of refraction of the material that the light travels through. So Milchberg and the team predicted that if they could create a rapid change in the refractive index at selected locations in the pulse as it flew by, it would flick that portion of the pulse. However, if the entire pulse passes through the area with a new index of refraction, they predicted that there would be no change in OAM—like having someone on the opposite side of a merry-go-round trying to slow it down while you are trying to speed it up.

To test their theory, the team needed to develop the ability to flick a small section of a pulse moving at the speed of light. Luckily, Milchberg’s lab already had invented the appropriate tools. In multiple previous experiments, the group has manipulated light by using lasers for the rapid generation of plasmas—a phase of matter in which electrons have been torn free from their atoms. The process is useful because the plasma brings with it a new index of refraction.

In the new experiment, the team used a laser to make narrow columns of plasma, which they called transient wires, that are small enough and flash into existence quickly enough to target specific regions of the pulse mid-flight. The index of refraction of a transient wire plays the role of a child pushing the merry-go-round.

The researchers generated the transient wire and meticulously aligned all their beams so that the wire precisely intercepted the desired section of the OAM-carrying pulse. After part of the pulse passed through the wire and received a flick, the pulse reached a special optical pulse analyzer the team invented. As predicted, when the researchers analyzed the collected data, they found that the refractive index flick changed the pulse’s transverse OAM.

They then made slight adjustments in the orientation and timing of the transient wire to target different parts of the light pulse. The team performed multiple measurements with the transient wire crossing through the top and bottom of two types of pulses: STOVs that already carried transverse OAM and a second type called a Gaussian pulse without any OAM at all. For the two cases, corresponding to pushing an already spinning or a stationary merry-go-round, they found that the biggest push was achieved by applying the transient wire flick near the top and bottom edges of the light pulse. For each position, they also adjusted the timing of the transient wire laser on various runs so that different amounts of the pulse traveled through the plasma and the vortex received a different amount of kick. Researchers who previously generated vortices of light that they describe as “edge-first flying donuts” have now performed experiments where they disturb the path of the vortices mid-flight to study changes to their momentum. Image credit: Intense Laser-Matter Interactions Lab, UMD

Researchers who previously generated vortices of light that they describe as “edge-first flying donuts” have now performed experiments where they disturb the path of the vortices mid-flight to study changes to their momentum. Image credit: Intense Laser-Matter Interactions Lab, UMD

The team also showed that, like a merry-go-round, pushing with the spin adds OAM and pushing against it removes OAM. Since opposite edges of the optical merry-go-round are traveling in opposite directions, the plasma wire could fulfill both roles by changing its position even though it always pushed in the same direction. The group says the calculations they performed using their theory are in excellent agreement with the results from their experiment.

“It turns out that ultrafast plasma provides a precision test of our transverse OAM theory,” says Milchberg. “It registers a measurable perturbation to the pulse, but not so strong a perturbation that the pulse is completely messed up.”

The team plans to continue exploring the physics associated with transverse OAM. The techniques they have developed could provide new insights into how OAM changes over time during the interaction of an intense laser beam with matter (which is where Milchberg’s lab first discovered transverse OAM). The group plans to investigate applications of transverse OAM, such as encoding information into the swirling pulses of light. Their results from this experiment demonstrate that the naturally occurring fluctuations in the index of refraction of air are too slow to change a pulse’s transverse OAM and distort any information it is carrying.

“It's at an early stage in this research,” Hancock says. “It's hard to say where it will go. But it appears to have a lot of promise for basic physics and applications. Calling it exciting is an understatement.”

Story by Bailey Bedford

In addition to Milchberg, and Hancock, graduate student Andrew Goffin and UMD physics postdoctoral associate Sina Zahedpour were co-authors.