Sudden Breakups of Monogamous Quantum Couples Surprise Researchers

- Details

- Published: Monday, January 05 2026 01:40

Quantum particles have a social life, of a sort. They interact and form relationships with each other, and one of the most important features of a quantum particle is whether it is an introvert—a fermion—or an extrovert—a boson.

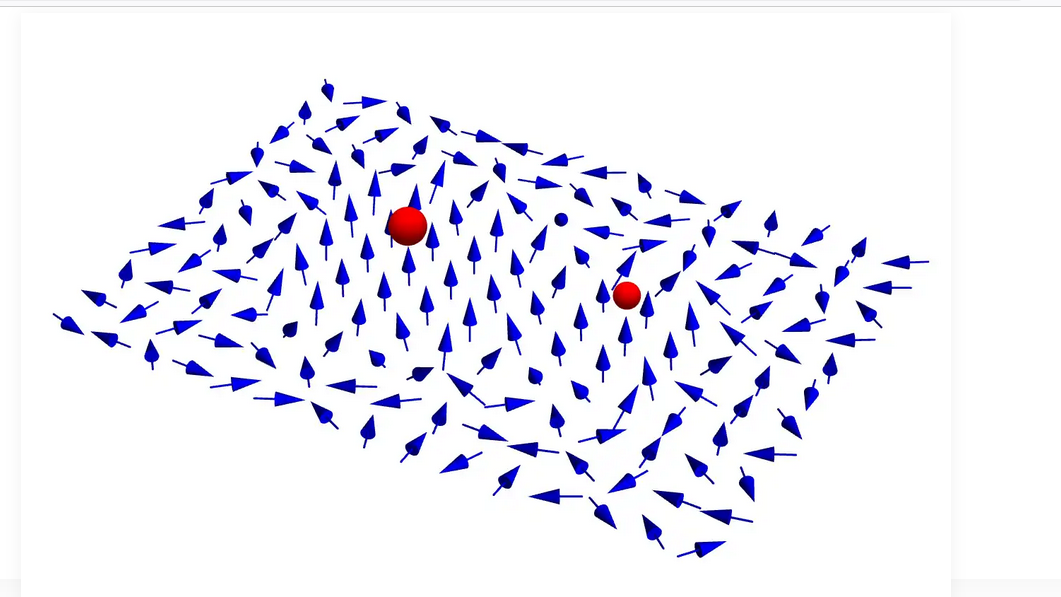

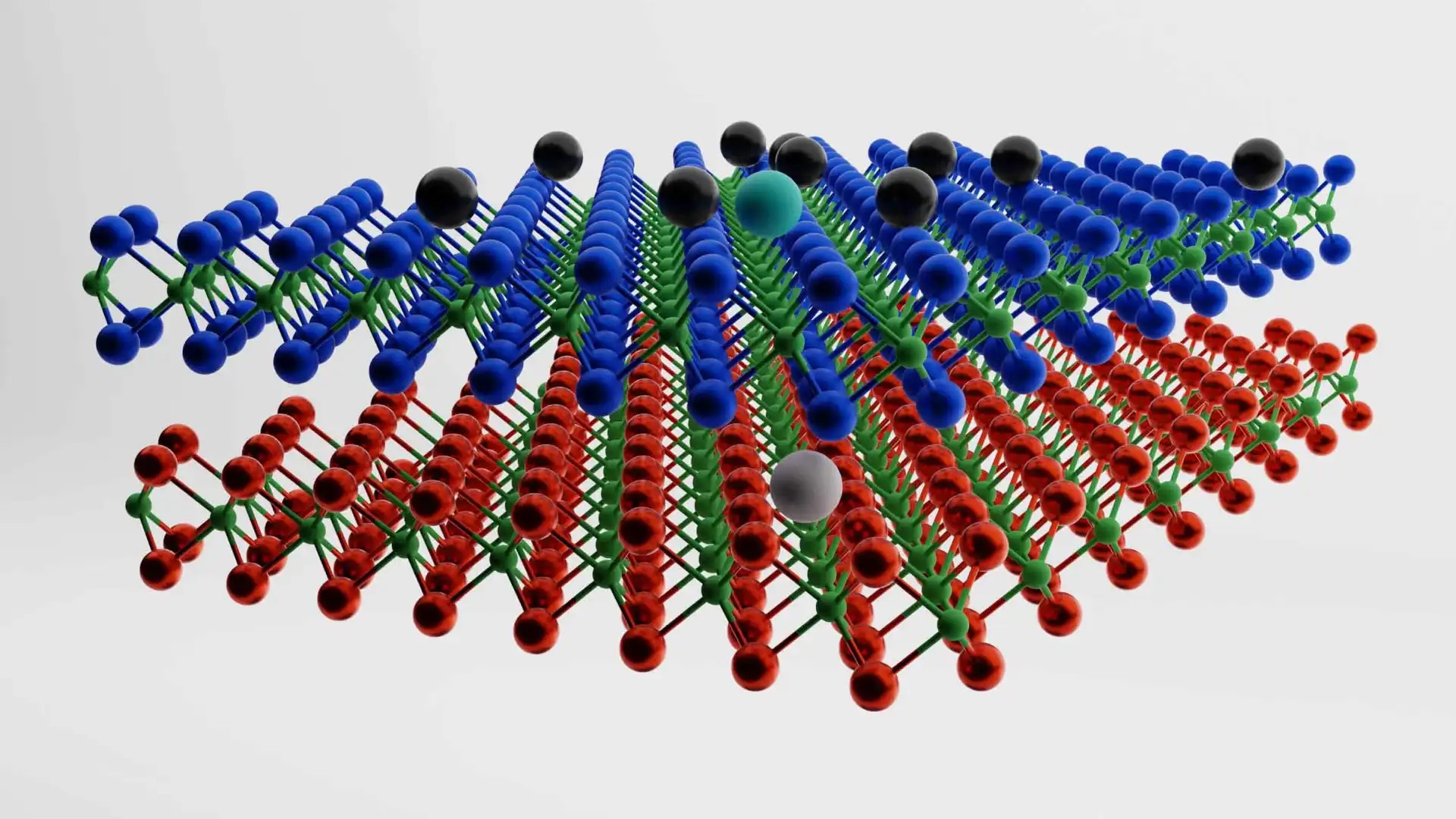

Extroverted bosons are happy to crowd into a shared quantum state, producing dramatic phenomena like superconductivity and superfluidity. In contrast, introverted fermions will not share their quantum state under any condition—enabling all the structures of solid matter to form. An exciton forms when an electron pairs up with a hole—a mobile particle-like void in a material where an electron is missing from an atom. When paired up as an exciton, a hole and electron normally travel around together as an exclusive couple, but a new experiment probes what happens when conditions in a material break up the pair. In the image, a hole (grey sphere) resides in the bottom layer of a stacked material and is paired to an electron in the top layer (cyan sphere). None of the electrons present in the top layer (black spheres) are willing to share a spot in the material with each other or the electron in the exciton. (Credit: Mahmoud Jalali Mehrabad/JQI)

An exciton forms when an electron pairs up with a hole—a mobile particle-like void in a material where an electron is missing from an atom. When paired up as an exciton, a hole and electron normally travel around together as an exclusive couple, but a new experiment probes what happens when conditions in a material break up the pair. In the image, a hole (grey sphere) resides in the bottom layer of a stacked material and is paired to an electron in the top layer (cyan sphere). None of the electrons present in the top layer (black spheres) are willing to share a spot in the material with each other or the electron in the exciton. (Credit: Mahmoud Jalali Mehrabad/JQI)

But the social lives of quantum particles go beyond whether they are fermions or bosons. Particles interact in complex ways to produce everything we know, and interactions between quantum particles are key to understanding why materials have their particular properties. For instance, electrons are sometimes tightly locked into a relationship with a specific atom in a material, making it an insulator. Other times, electrons are independent and roam freely—the hallmark of a conductor. In special cases, electrons even pair up with each other into faithful couples, called Cooper pairs, that make superconductivity possible. These sorts of quantum relationships are the sources of material properties and the foundations of technologies from the simplest electrical wiring to cutting-edge lasers and solar panels.

Professor and JQI Fellow Mohammad Hafezi and his colleagues set out to investigate how adjusting the ratio of fermionic particles to bosonic particles in a material can change the interactions in it. They expected fermions to avoid each other as well as the bosonic counterparts chosen for the experiment, so they predicted that large crowds of fermions would get in the way and prevent bosons from moving far. The experiment revealed the exact opposite: When the researchers attempted to freeze the bosons in place with a barricade of fermions, the bosons instead started traveling quickly.

“We thought the experiment was done wrong,” says Daniel Suárez-Forero, a former JQI postdoctoral researcher who is now an assistant professor at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County. “That was the first reaction.”

But they went on to thoroughly check their results and eventually came up with an explanation. The researchers shared their experiments and conclusions in an article published on Jan. 1, 2026 in the journal Science. They had stumbled onto a way to host a quantum party where the particles throw their social norms out the window, producing a dramatic—and potentially useful—change in behavior.

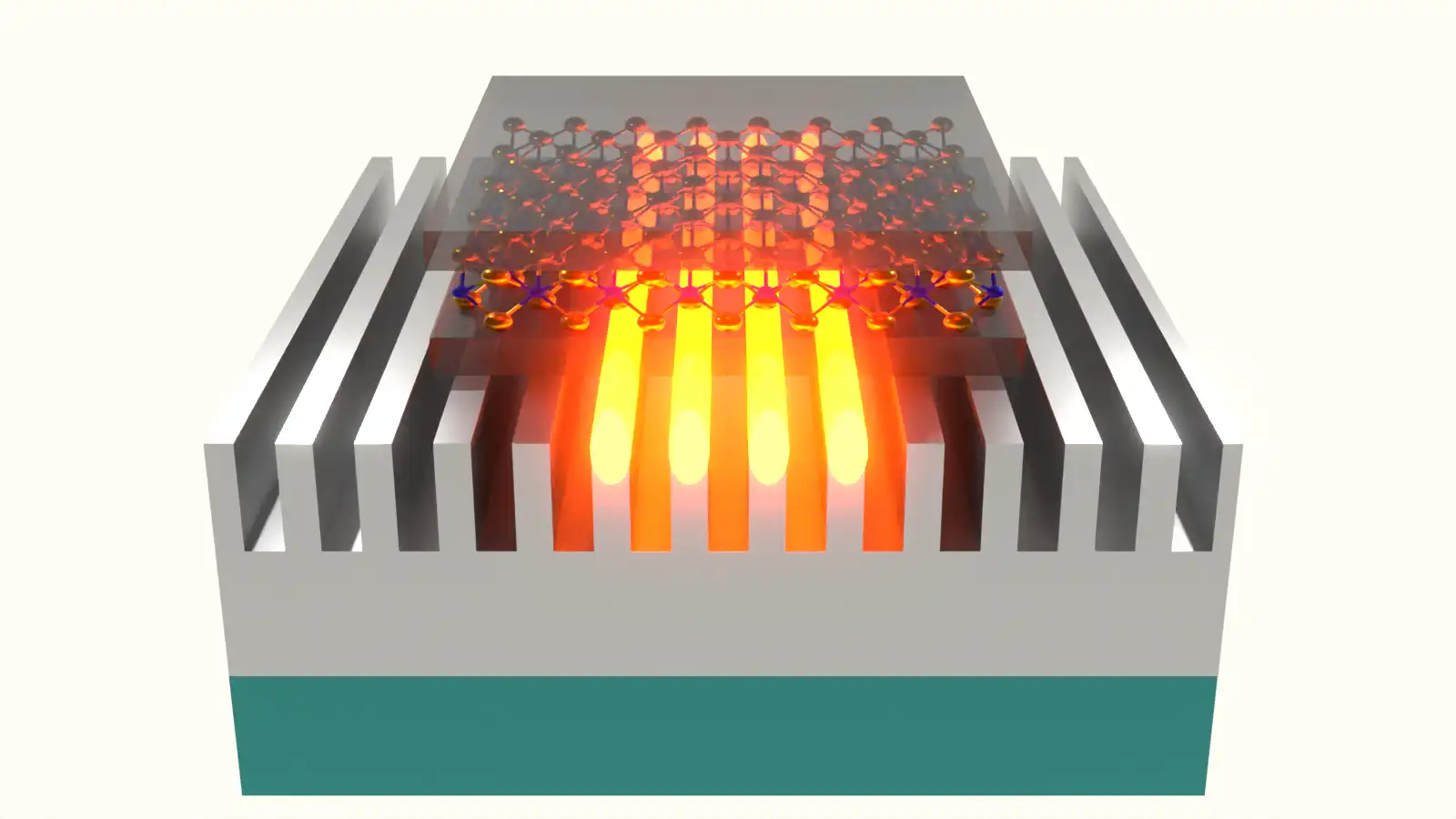

The group’s experiment explored the interactions electrons have with each other and with couples formed from an electron and a hole. Holes aren’t quite real particles like electrons. Instead, they are quasiparticles—they behave like particles but only exist as a disturbance of the surrounding medium. A hole is the result of a material missing an electron from one of its atoms, leaving an uncompensated positive charge. The hole can move around and carry energy like a particle within the material, but it can never leave the host material. And if an electron ever falls into a hole, the hole disappears.

Sometimes, electrons and holes form an atom-like arrangement (with the hole playing the role of a proton). When this happens, the hole and electron move together and behave like a single quantum object that researchers call an exciton. It normally takes energy to break up the particles in an exciton, so as an exciton moves the hole and electron pretty much always stick together. This fact led physicists to label the exciton relationship as “monogamous.”

The composite excitons are bosons, while individual electrons are fermions. Together, the two provided a suitable cast for the group’s experiments on fermion and boson interactions.

“At least this was what we thought,” said Tsung-Sheng Huang, a former JQI graduate student of the group who is now a postdoctoral researcher at the Institute of Photonic Sciences in Spain. “Any external fermion should not see the constituents of the exciton separately; but in reality, the story is a little bit different.”

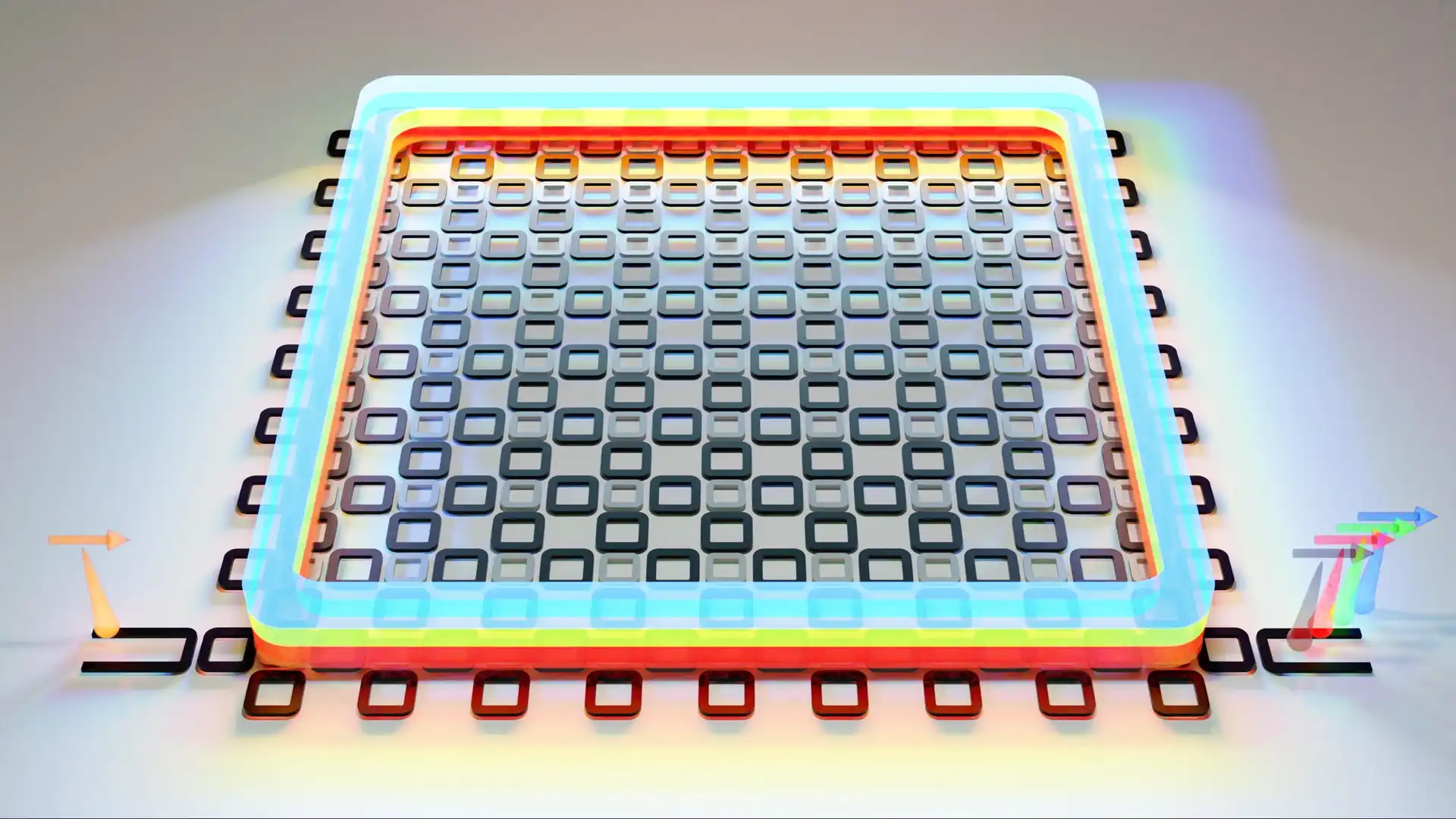

To get the particles they needed and a suitable way to control them, the researchers created a material with the qualities they needed for their experiment by carefully aligning a layer of one thin material on another thin material with just the right alignment. The material’s properties allowed them to easily create excitons that live for a relatively long time, while its structure kept things orderly by providing a neat grid of spots where an exciton or an unpartnered electron need to reside.

Because of the structure, the electrons and excitons don’t see the material as a standing-room-only concert venue but, instead, as a restaurant set up for Valentine’s Day—all the floor space is crammed with small, intimate tables. In the material, every exciton and lone electron needs to be sat at a table, and the introverted solo electrons won’t share—either with each other or with an exciton.

However, excitons generally aren’t content to stay in their original seats. They tend to move around. But instead of brazenly walking across the room, an exciton surreptitiously hops from one adjacent empty table to the next—sometimes resulting in an inefficient detour around a cluster of occupied tables.

During an experiment, the researchers can host trillions of particles in the material’s seating plan, and they can control the number of excitons and electrons that are free to move through the room. To add or remove electrons, the researchers apply different electrical voltages, which can force electrons into or out of the material. To add excitons, they summon them from the existing material. The researchers can shine a specific color of laser on the material, and its atoms will absorb the light. The energy from the laser knocks electrons loose from the atoms and creates excitons.

The top half of the image shows the layered structure of a material that can host free-moving electrons (the black spheres) and excitons made of a hole (white sphere) partnered with a particular electron (cyan sphere). The bottom of the image shows the quantum landscape created by the material for the electrons and excitons. It contains many distinct locations where the electrons and excitons want to reside. The exciton can move to nearby empty spots but not one already occupied by an electron. (Credit: Mahmoud Jalali Mehrabad/JQI)

The researchers were able to track where the excitons they created end up; they just watched for the signs of their eventual destruction. When an exciton’s electron and hole eventually combine, the extra energy it carried must go somewhere, and it is commonly emitted as light. The researchers collected this light and used it as a marker of the final positions of the excitons. This let them determine how much each cluster of excitons diffused through the material even though they don’t watch their individual journeys.

“We can basically do any ratio,” Suárez-Forero says. “We can populate the system with only bosons, only fermions, or any ratio. And the diffusivity, the way in which the bosons move, changes a lot depending on the number of particles of each species.”

In the experiment, the researchers systematically adjusted the electron density and deduced what they could from the resulting changes in the diffusion of the bosons. They used the movement of the excitons as an indication of their interactions with the electrons and each other, turning each group of excitons into an experimental sensor.

When there were very few electrons, the researchers expected electrons to essentially never come across each other and thus to not have much influence on each other or the excitons. In contrast, abundant electrons are expected to avoid each other and to get in the way of the excitons.

Things started out as expected with the excitons traveling shorter and shorter distances as the electron population was dialed up. The excitons increasingly had to find a winding path around electrons instead of taking a mostly straight path.

Eventually, the experiment reached the point where almost every table was occupied by an electron. The researchers expected this to essentially halt exciton diffusion, but instead, they observed a sudden jump in the mobility of the excitons. Despite the fact that the excitons should have had their paths blocked, the distance they moved dramatically increased.

“No one wanted to believe it,” says Pranshoo Upadhyay, a JQI graduate student and the lead author of the paper. “It’s like, can you repeat it? And for about a month, we performed measurements on different locations of the sample with different excitation powers and replicated it in several other samples.”

They even tried the experiment in a different lab when Suárez-Forero concluded his postdoctoral work at JQI and spent some time as a research scientist at the University of Geneva.

“We repeated the experiment in a different sample, in a different setup, and even in a different continent, and the result was exactly the same,” Suárez-Forero says.

They also had to check that they weren’t misinterpreting the results. They were only seeing the exciton diffusion, not actually watching the interactions. They were relying on mathematical theories to explain the results, and they needed to make sure a mistake wasn’t hiding in their math.

The team formed a strong theoretical and experimental collaboration to figure out what was going on.

“We spent months going back and forth with theorists, trying out different models, but none of them captured all our experimental observations,” Upadhyay says. “Eventually we realized that the excitons sit differently than the free electrons and holes in our system. That was the turning point—when we began thinking of the exciton beyond monogamy.”

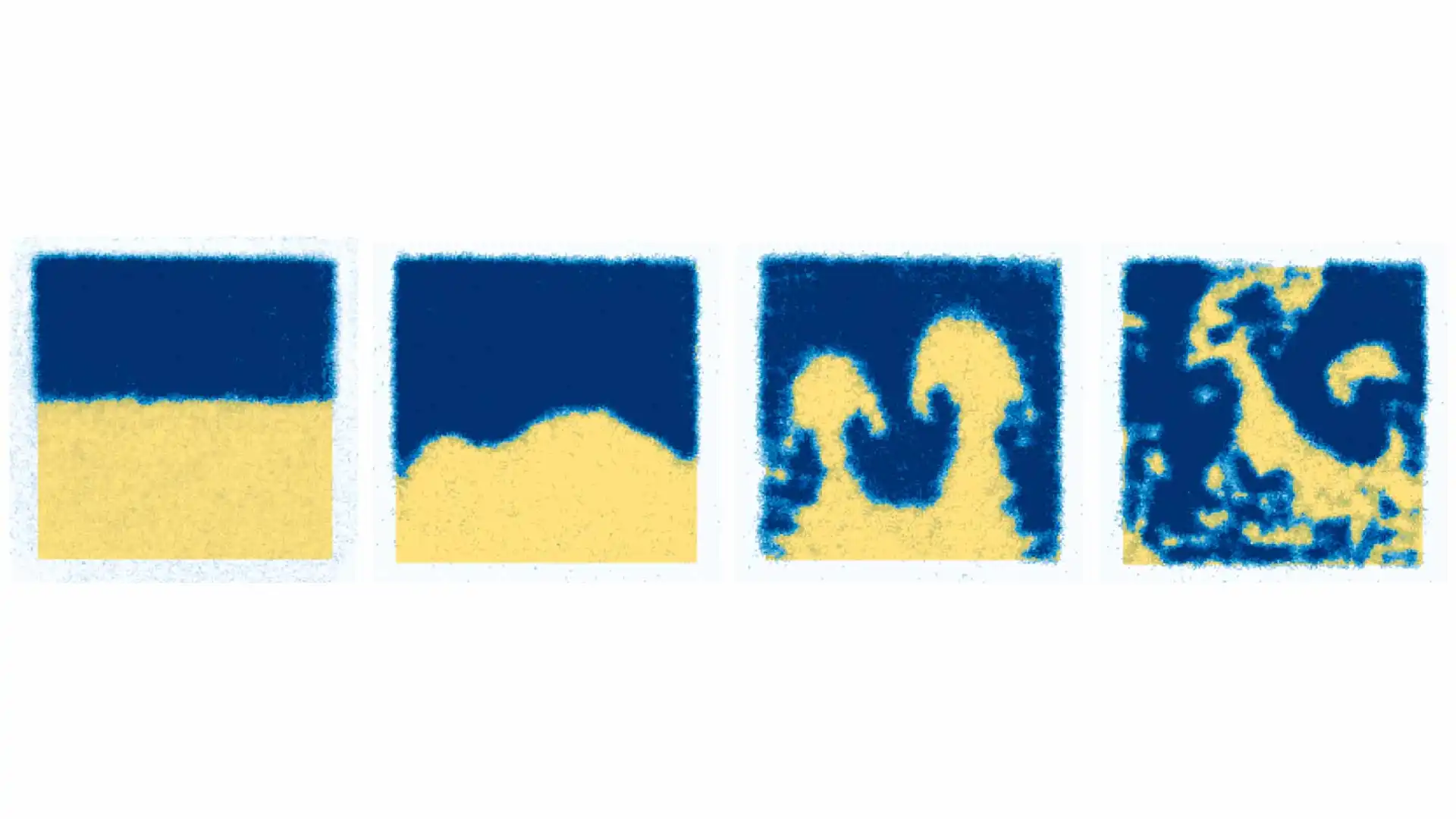

The team concluded that the very crowded conditions were making the excitons give up on monogamy, so the researchers described the phenomenon as “non-monogamous hole diffusion.” Essentially, the surprising result occurred when the experimenters flooded the material—the metaphorical restaurant—with a bunch of electrons, each claiming a table to itself. The researchers determined that when the population of available electrons got sufficiently lopsided, the holes in each exciton saw all the other electrons as identical to the one they were already with; the normal rule of exciton monogamy broke down.

The rapid diffusion was caused by holes suddenly ditching their long-term electron partners. Instead of each working its way from table to table with the same electron, the holes were doing a speed dating round with electron after electron—allowing each exciton to make a beeline to its destination. Without the normal winding path around all the single electrons, each exciton travelled much farther before giving off its signature flash of destruction.

All the researchers needed to do to trigger this lopsided dating pool and rapid travel was adjust the voltage. Controlling voltages is no problem for existing devices, so the technique has broad potential to be conveniently integrated into future experiments and technologies that exploit excitons, like certain solar panel designs.

The researchers are already using this insight into how excitons and electrons can interact to interpret other experiments. They are also working to apply their new understanding of these materials to achieve greater control of the quantum interactions that they can induce in experiments.

“Gaining control over the mobility of particles in materials is fundamental for future technologies,” Suárez-Forero says. “Understanding this dramatic increase in the exciton mobility offers an opportunity for developing novel electronic and optical devices with enhanced capabilities.”

Original story by Bailey Bedford: https://jqi.umd.edu/news/sudden-breakups-monogamous-quantum-couples-surprise-researchers

In addition to Hafezi, who is also a Minta Martin professor of electrical and computer engineering and physics at the University of Maryland and a senior investigator at the National Science Foundation Quantum Leap Challenge Institute for Robust Quantum Simulation; Upadhyay; Suárez-Forero and Huang, co-authors of the paper include JQI graduate students Beini Gao and Supratik Sarkar; former JQI postdoctoral researcher Deric Session who is now a systems scientist at Onto Innovation; Mahmoud Jalali Mehrabad, a former JQI postdoctoral researcher who is now a research scientist at MIT; Kenji Watanabe and Takashi Taniguchi, who are researchers at the National Institute for Material Science in Japan; You Zhou, who is an assistant professor at the University of Maryland’s School of Engineering; and Michael Knap, who is a professor at the Technical University of Munich in Germany.

This research was funded in part by the National Science Foundation and the Simons Foundation.