Connecting the Quantum Dots

- Details

- Published: Wednesday, January 29 2025 01:40

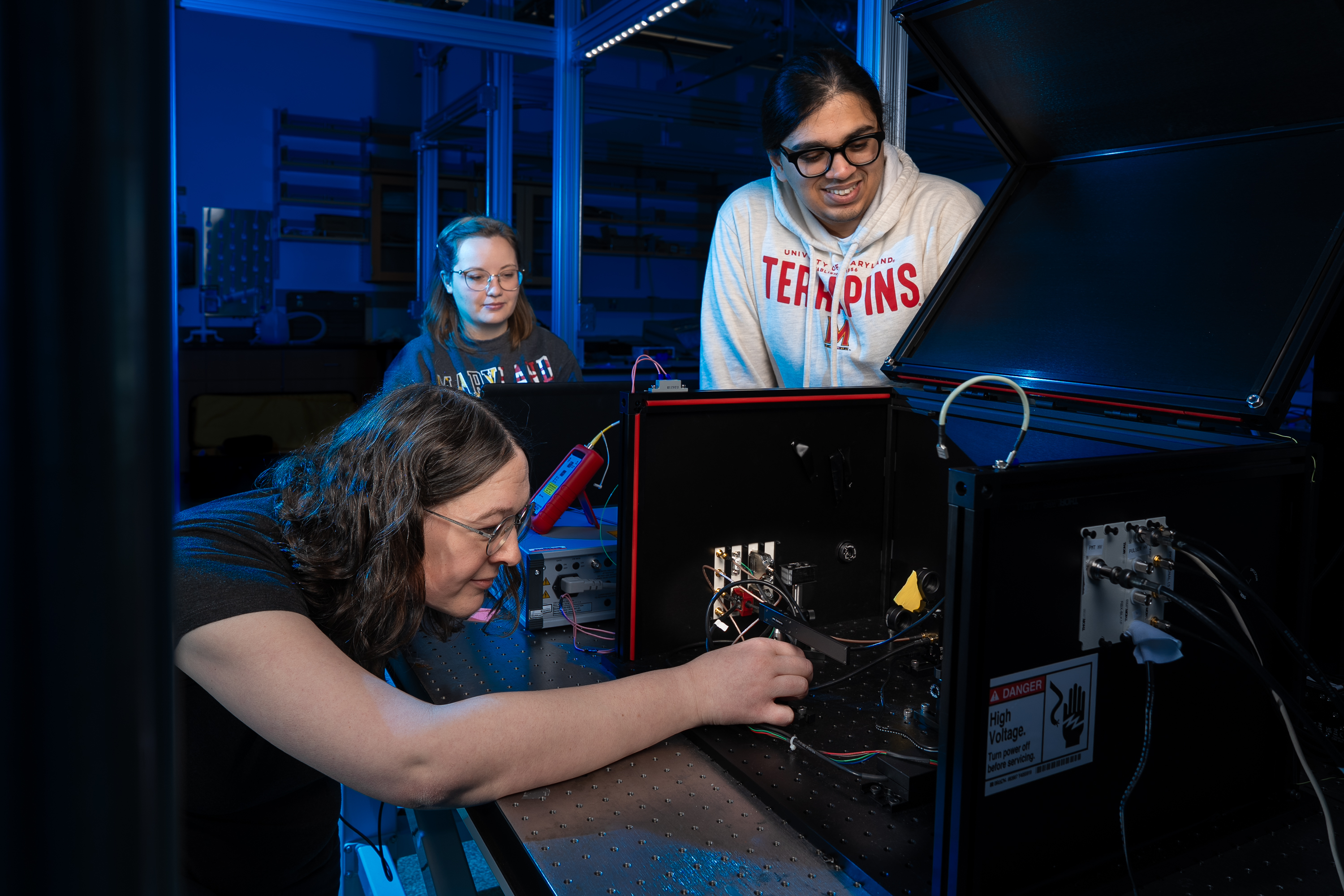

Physics Ph.D. student Anantha Rao tests ways to build bigger and better quantum computers.

Anantha Rao grew up in Bengaluru, a city known as India’s tech hub due to its bustling startup culture and many international IT corporations. While many of Rao’s peers pursued engineering and related subjects, Rao’s love of science and knack for solving mathematical problems nudged him in a different direction.

“Everyone around me was an engineer or wanted to be one, and that is one thing I did not want to be,” Rao said. “I had this rebellious nature of going against the crowd, but I also wanted to solve fundamental problems in the basic sciences for the love of it—not for immediate applications.”

Rao discovered his calling after winning a high school physics competition. As a prize, he received a book written by Richard Feynman, a theoretical physicist who laid the groundwork for the field of quantum computing more than 40 years ago, and the field’s endless applications captivated Rao.

“Quantum computing has applications in studying how drug molecules bind to receptors or decrypting credit card transactions. You could study models of how the universe was created or see how the first molecule came into the picture,” Rao said. “Using ideas from quantum mechanics and computer science, you can also build better quantum computers, which is the problem that I’m looking at today.”

Now a Ph.D. student in the University of Maryland’s Department of Physics and Joint Center for Quantum Information and Computer Science (QuICS), Rao probes the fundamental physics that could power the next generation of quantum computers. He said he’s grateful for the chance to pursue that challenge in the “Capital of Quantum” at UMD.

“UMD is one of the top schools in the world for quantum information, especially theory,” Rao said. “Ten years ago, if someone told me that I'd be here now, I would feel like it is a dream.”

Tackling malaria with tech

Before moving to the United States, Rao was a full-time physics student and part-time entrepreneur in India. While Rao was enrolled in a combined bachelor’s and master’s program at the Indian Institute of Science Education and Research Pune, he cofounded a startup to develop diagnostic tools for diseases like malaria, a mosquito-borne infection that kills an estimated 608,000 people per year, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The software he developed, dubbed Deep Learning for Malaria Detection (DeleMa Detect), relied on artificial intelligence (AI) to search patients’ blood smear images for the signs and stages of malaria infection. This technology is packed into a small, portable device, reducing the need for lab tests that can be costly and inaccessible in many parts of the world.

Rao’s startup received a $50,000 grant and won top prize at the International Genetically Engineered Machine (iGEM) 2021 Startup Showcase. Rao has since moved on to other projects but said his early entrepreneurial experience taught him lessons about project leadership and collaboration that he applies to his research every day.

“I learned a lot about AI during my brief stint with entrepreneurship, and that’s something I've been working on lately—using AI to solve problems in physics,” Rao said. “My main motivation now is: What are the toughest problems out there and how can I solve them? Rao at TU Delft.

Rao at TU Delft.

Since joining UMD’s physics Ph.D. program in 2023, he has been working to identify—and answer—those questions, one at a time.

The making of MAViS

One of Rao’s biggest ongoing projects is a collaboration between UMD, the National Institute of Standards and Technology and Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands. He has been leading the Modular Autonomous Virtualization System for Two-Dimensional Semiconductor Quantum Dot Arrays (MAViS) project, which aims to advance research that could lead to bigger and better quantum dot-based quantum computers.

Central to this concept are quantum dots, tiny semiconductor particles that serve as the building blocks of some quantum computers. These quantum computers operate at temperatures close to absolute zero, or −273.15 degrees Celsius—conditions that prompt the chips to engage in quantum mechanical behavior.

“The chips in your phone and chips in your laptop are made up of semiconductors, and similarly, we have quantum computers made out of semiconductors, except they operate at the coldest temperatures in the universe,” Rao explained. “The problem is you can't control them very well and you have a lot of unwanted interactions coming in.

To control each quantum dot, voltages must be applied to electrodes in their vicinity. Isolating this task can be tricky, though, because quantum dots are spaced just a few nanometers apart.

“What MAViS offers is a way to independently control each quantum dot in a very scalable and efficient way. This is a process called virtualization,” Rao explained. “Most importantly, it’s completely automatic. You press a button and MAViS solves a lot of equations faster than any human.”

By finding ways to offset unwanted interactions, which can introduce errors, researchers can make quantum computers run more efficiently and accurately. MAViS also uses “a little bit of AI” to enable corrections in real-time, Rao said.

Rao and his collaborators have seen encouraging results after testing MAViS on some of the world’s largest quantum dot devices in the Netherlands. MAViS successfully enabled researchers to operate and more efficiently control quantum dots, which in turn helps them control qubits—the fundamental building blocks of quantum computers.

Rao explained that one of the benefits of MAViS is that it works quickly and could free up time for researchers to focus on deeper tasks.

“We were able to do a task in about four hours that would have taken a month or two months of human effort,” Rao said. “Without MAViS, a lot of people with doctorate degrees would have needed to stare at computer screens and analyze complicated images to solve this problem. Now, researchers can automatically ‘virtualize’ their quantum dots and perform interesting experiments.”

Aside from his research with MAViS, Rao said his research on semiconductor qubits has also revealed some unusual physics, including elusive crystals made entirely of electrons.

“Another question in my research is: If you have these semiconductor quantum dots or quantum computers, what is some interesting physics that one could study in one dimension or two dimensions?” Rao said. “We've found evidence that exotic phases of matter—something called Wigner crystals—could be found in these devices.”

Giving back

As Rao dives deeper into quantum physics, he continually seeks ways to share his knowledge. MAViS and many of Rao’s past research projects involve open-source code so that the community at large can benefit.

“Since undergrad, I’ve wanted to give back to the community as I’ve learned things, and one way is through open-source projects and mentoring other students,” said Rao, who also worked as a teaching assistant and served on graduate student committees at UMD. “We hope to eventually make MAViS open source so that people anywhere in the world can build better, scalable quantum-dot quantum computers.”

After Rao graduates, he hopes to find a job that will enable him to keep tackling the big questions in quantum physics, whether that’s in academia or private industry.

“My pursuit is the best research and the best science that I can do today, and I believe that approach will give me the right opportunity in an academic lab or industry lab,” Rao said. “There are a lot of problems to solve in quantum, and I’m working toward solving them one at a time.”

Written by Emily Nunez; published March, 2025