From Space Science to Science Fiction

- Details

- Category: Department News

- Published: Wednesday, January 29 2025 01:40

From her earliest years, Adeena Mignogna (B.S. ’97, physics; B.S. ’97, astronomy) always saw space in her future. It started with “Star Wars.”

“I have memories of watching the first ‘Star Wars’ movie with R2-D2 and C-3PO when I was about 6 years old and I really connected with the robots, wanting to know how we make this a reality,” she recalled. “For a while, I thought I was going to grow up and have my own company that would make humanoid robots, but the twist was, we were going to live and work on the moon. I could even picture my corner office and the view of the moon out the window.” Adeena Mignogna

Adeena Mignogna

For Mignogna, that boundless imagination and her childhood fascination with space and science launched two successful and very different careers—one in aerospace as a mission architect at Northrop Grumman, developing software and systems for satellites, and the other as a science fiction writer, spinning stories of robots, androids and galactic adventures in her many popular books. For Mignogna, space science and science fiction turned out to be a perfect combination.

“I think of it as kind of like a circular thing—science fiction feeds our imagination, which possibly inspires us to do things in science. And science feeds the science fiction,” Mignogna explained. “Working in the space industry is something that I always wanted to do, and I always wanted to write as well, so I’m glad that I'm really doing it.”

Drawn to science

The daughter of an engineer, Mignogna was always drawn to science and technology.

“I am my father's daughter,” she said. “My dad brought home computers, and I learned to program in BASIC, so it was kind of always obvious that I was always going to do something STEM-ish.”

Inspired by the real-life missions of NASA’s space shuttle and the Magellan deep space probe and popular space dramas like “Star Wars” and “Star Trek,” Mignogna’s interest in aerospace blossomed into a full-on career plan. As she prepared to start college at the University of Maryland in the early ’90s, she began steering toward two majors.

“At first, I thought maybe I'm going to major in astronomy because I loved space and space exploration,” Mignogna recalled. “But my high school physics teacher had degrees in physics, and he had done a lot of different things. He had worked at Grumman during the Apollo era, he had done astronomy work, and so I was like, ‘Okay, if I major in physics, I could do space stuff, I could do anything.’ So in the end, I majored in both.”

Surprisingly—at least to her—at UMD, Mignogna discovered she loved physics.

“What do I love about physics? It's very fundamental to how everything works,” she explained. “I used to tease my friends in college who majored in other sciences that at the end of the day, they were all just studying other branches of physics—like math is just the tool we use to describe physics and chemistry is an offshoot of atomic physics and thermodynamics. And even though I was making fun, I do probably think there's some truth to that, and that might be why I like physics so much.”

Hands-on with satellites

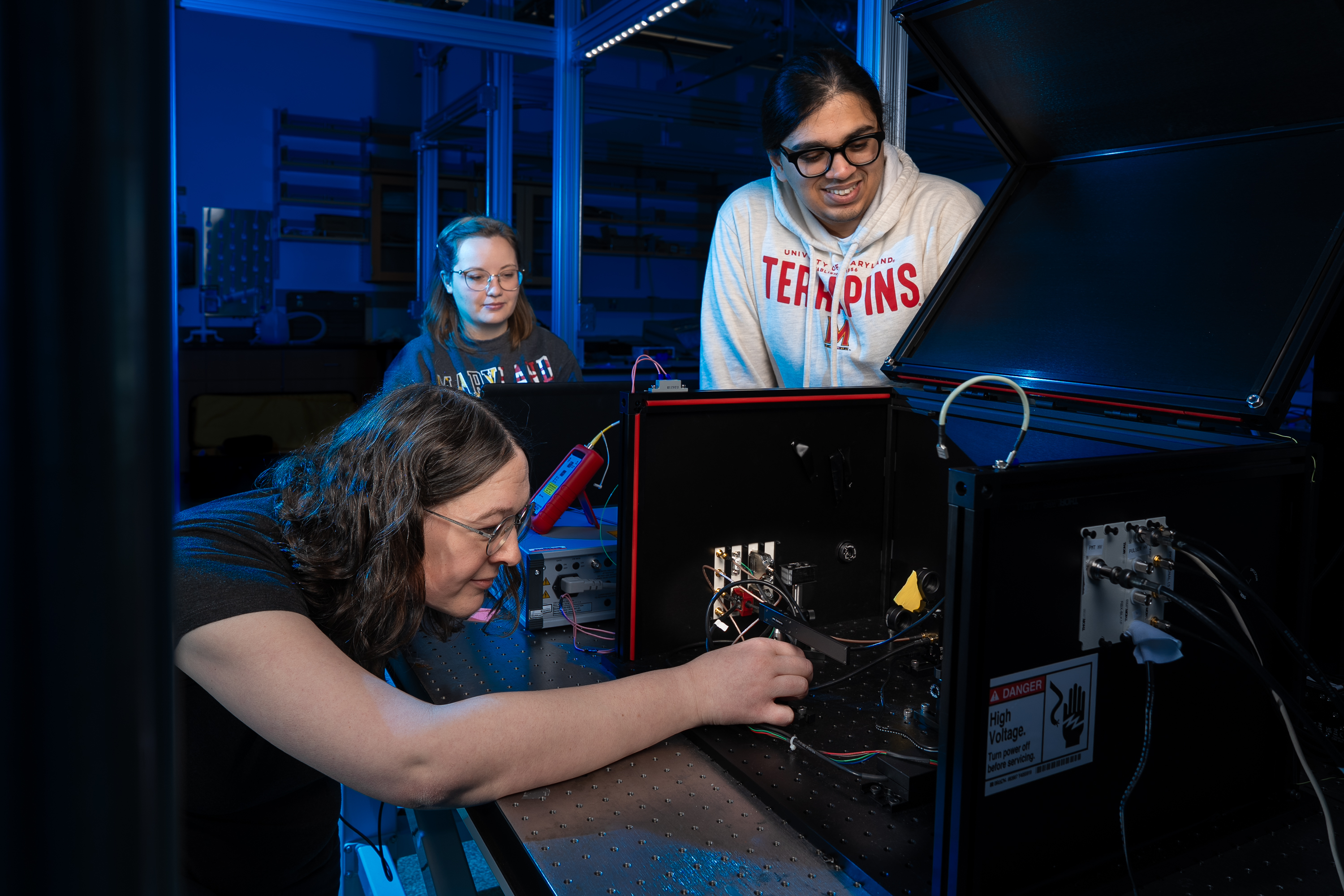

By her sophomore year, Mignogna got her first hands-on experience with aerospace technology.

“I wound up getting a job in the Space Physics Group, and they built instrumentation for satellites,” Mignogna explained. “I happened to learn about this at the right time when they were looking for students for a new mission, and I worked on that mission from day one till we turned the instrument over to [NASA’s] Goddard Space Flight Center, which was very cool.”

Working in that very hands-on lab assembling and sometimes reassembling science instruments that would eventually fly in space, Mignogna realized she was on the right path.

“I was touching spaceflight hardware. I was touching stuff that was going into space,” she recalled. “It was really exciting.”

For Mignogna, working side by side with space scientists at UMD and getting hands-on training in skills like CAD drafting gave her the tools she needed to land her first job at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center.

Mignogna eventually landed at Orbital Sciences Corporation, which later became part of Northrop Grumman. For the next 16 years—earning her master’s degree in computer science from the Georgia Institute of Technology along the way—she expanded her space software and systems expertise and became a leader in Northrop’s satellite engineering program.

“On the software side, I worked on our command and control software. We have a software suite that controls the satellites, and what I loved was that it gave me exposure and insight into so many different kinds of satellites,” Mignogna said. “With systems engineering, I’m able to go through what we call the full life cycle of the mission. When NASA says, ‘Hey, we need a satellite that's going to do X, Y, Z,’ as a systems engineer, we’re the ones who break that down, and I’m kind of the end-to-end broader picture person in that process. The group that I'm closely associated with today is responsible for Cygnus, which is one of the resupply capsules to the International Space Station.”

From science to science fiction

Over the years, as Mignogna’s career reached new heights so did her work as a science fiction writer, a creative effort that started when she was in high school.

“My dad was a fan of Isaac Asimov and Robert Heinlein, so I knew they were engineers and scientists who also wrote science fiction, and that was something I always wanted to do,” Mignogna said. “At first, I didn't think I could write novels, I thought I could only do short stories. But around 2009, I figured out I could, and I’ve been doing it ever since.”

With titles like “Crazy Foolish Robots” and “Robots, Robots Everywhere,” Mignogna’s Robot Galaxy Series combines science fiction with humor, philosophy and, of course, robots. Her latest book “Lunar Logic” is set on the moon, 100 years from now.

“There are humanoid robots, built and manufactured on the moon, and they live on the moon. And they don't know anything about humans or why they're there,” Mignogna explained. “And then little things happen and they start to question what's going on and why they're there and eventually they kind of figure it all out.”

In Mignogna’s sci-fi worlds, the only limit is her own imagination, which is exactly what makes her work as a writer so enjoyable.

“In my science fiction work, it’s my way or the highway,” she said. “I can write whatever I want, and I can make it however I want, and there's some satisfaction in that.”

For Mignogna, writing science fiction also provides an opportunity to advance another mission—to get more people interested and excited about science. In regular appearances at sci-fi conferences and other gatherings, Mignogna shares her passion for STEM, hoping to inspire the next generation of scientists—and everyone else.

“All this technology we have today comes from generations upon generations of fundamental science, technology, engineering, mathematics,” she explained, “so if we're going to do more things, we need people to go into these fields. “

As someone who’s always seen the importance of science in her own life, it’s a message she’s committed to sharing.

“You don't have to understand everything about science, but you can appreciate it,” Mignogna noted. “My hope is maybe if I can just connect with a few people indirectly or directly, I can make a difference.”

Written by Leslie Miller