Buonanno Elected to Italian National Academy of Sciences

- Details

- Published: Thursday, August 31 2023 02:46

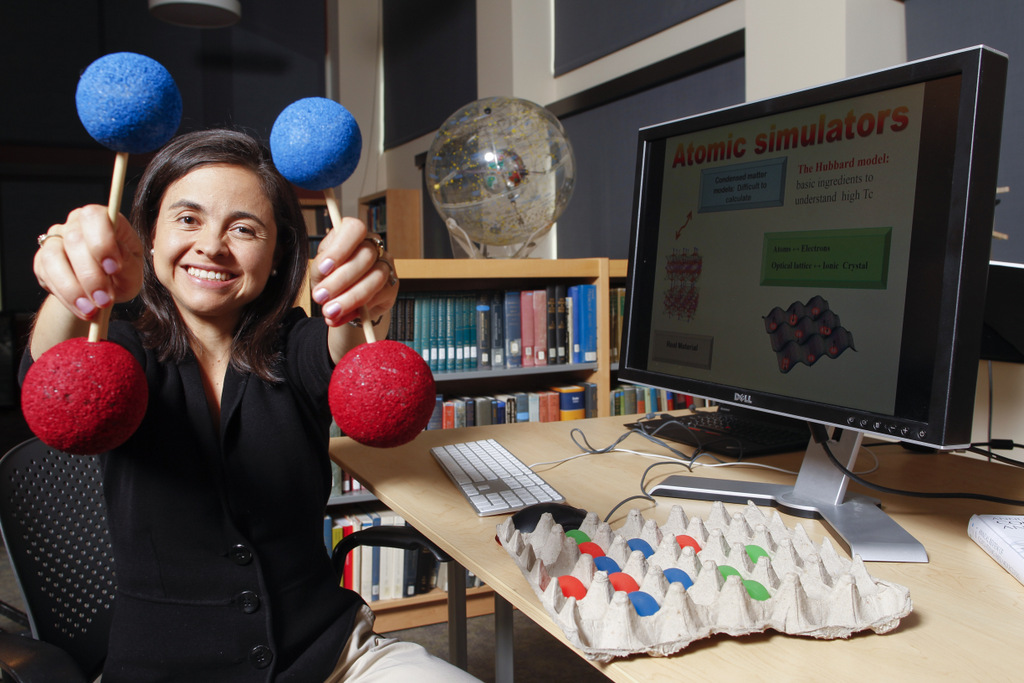

Alessandra Buonanno has been elected a member of the Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei, the Italian National Academy of Sciences.

Buonanno is the director of the Astrophysical and Cosmological Relativity Department at the Max Planck Institute for Gravitational Physics (Albert Einstein Institute) in Potsdam and a Research Professor at the University of Maryland.

Buonanno's research has spanned several topics in gravitational wave theory, data analysis and cosmology. She is a Principal Investigator of the LIGO Scientific Collaboration, and her waveform modeling of cosmological events has been crucial in the experiment’s many successes. Her work has merited election to the U.S. National Academy of Sciences and Leopoldina, the German National Academy of Sciences.

In 2018, Buonanno received the Leibniz Prize, Germany's prestigious research award. Other accolades include the Galileo Galilei Medal of the National Institute for Nuclear Physics (INFN), the Tomalla Prize, the Dirac Medal (with Thibault Damour, Frans Pretorius, and Saul Teukolsky) and the Balzan Prize (with Damour).

Alessandra Buonanno © A. Klaer

Alessandra Buonanno © A. Klaer

She is a Fellow of the American Physical Society and the International Society of General Relativity and Gravitation and a recipient of the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation Fellowship and the Richard A. Ferrell Distinguished Faculty Fellowship.

Buonanno, Charlie Misner, Peter Shawhan and others detailed UMD's contributions to gravitational studies in a 2016 forum, A Celebration of Gravitational Waves.