Grad school should challenge students’ minds but not their mental health, according to physics graduate students at the University of Maryland who are using scientific principles to understand their peers’ perspectives.

Formed in 2016, the Department of Physics’ Graduate Student Mental Health Task Force (MHTF) is a small, student-led group that conducts surveys to identify the unique challenges faced by physics graduate students. While all of the task force members are researchers, they are also part of the very group they are analyzing.

“When you are studying a population that you yourself are a part of, you come with your own biases, but you also come with an understanding of the group,” said physics graduate student and MHTF member Adam Ehrenberg. “And as somebody who for most of undergrad struggled with their mental health relatively openly, the MHTF seemed like a good way to think about those things in a slightly more official way.” Patrick Banner speaks with colleagues. Credit: Müge Karagöz

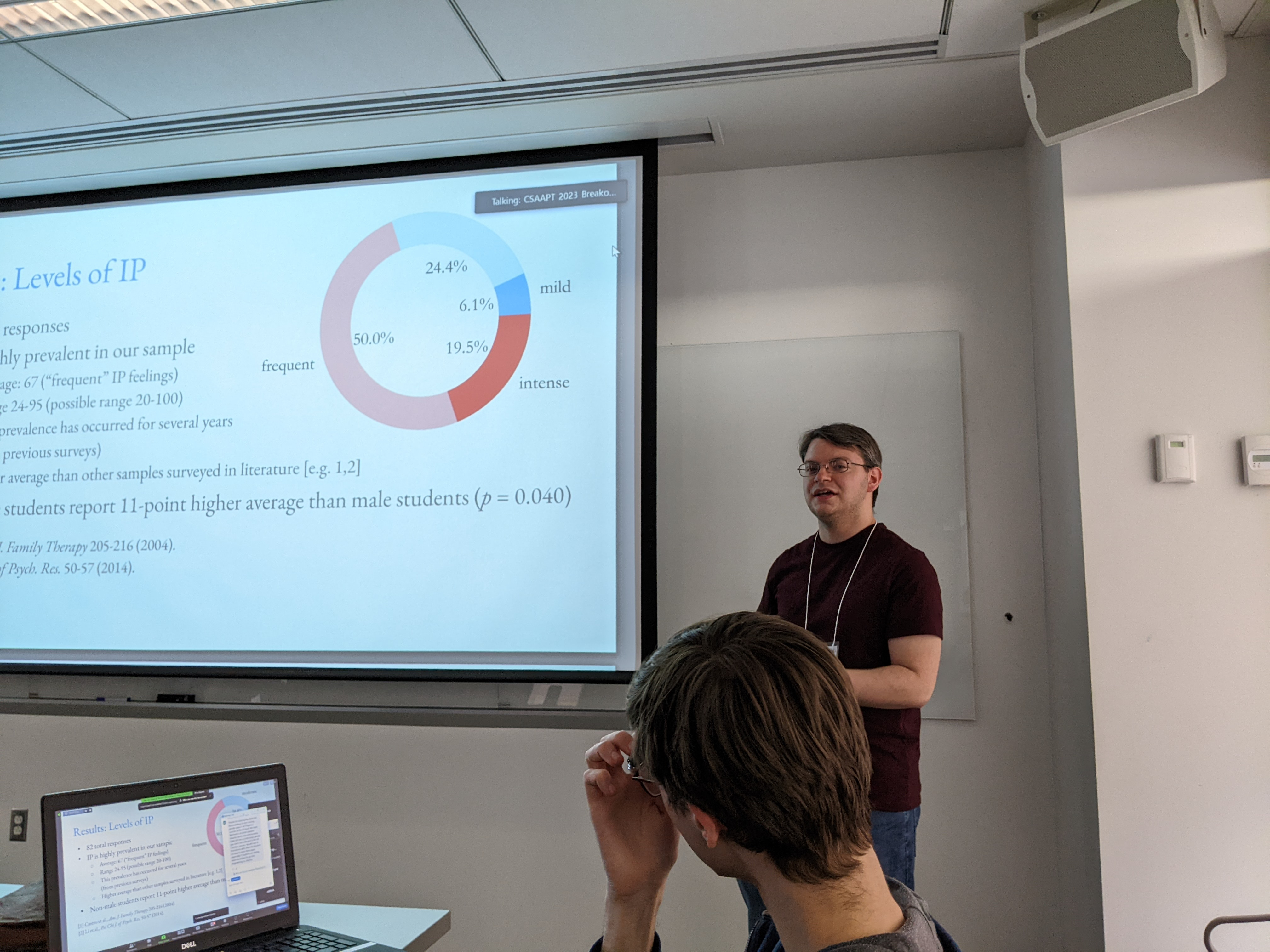

Patrick Banner speaks with colleagues. Credit: Müge Karagöz

The group works together to create surveys and get them approved by the campus Institutional Review Board—a recommended step for research involving human subjects. They then conduct statistical analyses to gather insights, which are condensed into a report and made publicly available online. Some surveys are broadly focused on students’ mental health, while others hone in on a specific issue.

The MHTF’s last report shed light on the high rate of impostor phenomenon among physics graduate students, especially among those who identify as female or nonbinary. People who experience this phenomenon often report feeling like “frauds” who have not earned their spot in a job or academic department.

Physics graduate student and MHTF member Patrick Banner explained that impostor phenomenon can cause anxiety, depression and low self-esteem, and can even prevent people from pursuing scholarships, fellowships or career opportunities.

“One really harmful aspect of impostor phenomenon is that someone experiencing it may feel that they do not deserve the opportunities they receive and therefore don't pursue them,” Banner said.

Banner said the task force’s next report, slated to publish sometime this semester, will dive deeper into this phenomenon and the role that academic advisors can play in a student’s experience.

“We had a specific question that we wanted to know, which is: Can the relationship between a student and their advisor affect impostor phenomenon feelings?” Banner said. “We asked not only questions about impostor phenomenon, but also about how students perceived their relationship with their advisor, and we can look at some quantitative correlations between those variables.”

While the MHTF is still analyzing data, preliminary results show that the quality of advising can affect how students view themselves and their place in the physics department. One of the group’s recommendations to advisors is to head off students’ feelings of inadequacy by helping them understand why they might be struggling with a task.

“Grad school is an inherently difficult process to go through, and there are always going to be struggles. Things are going to fail sometimes,” Banner said. “I think the best advisors are good at making that clear and reframing struggles to say, ‘No, it’s not you. This is a hard thing that you’re doing.’”

Steven Rolston, the physics department chair, said the MHTF’s methodical and compassionate approach to mental health has been “gratifying” to witness.

“They address the issue as scientists, using validated tools and raising the levels of statistical analysis as they refine their surveys,” Rolston said. “Simply addressing the topic out in the open—and showing their fellow students that they are not alone and that people do care—can make a big difference.”

The MHTF also produces and manages two resources for grad students: the UMD Physics Grad Student Guide and the Mental Health Resources page on the physics department website. To expand its scope even further, the MHTF started hosting more social events—from movie nights to coffee breaks—to help students feel more connected with their peers.

In 2021, MHTF members participated in a mental health panel hosted by the American Physical Society and, more recently, shared preliminary results of their newest survey during a meeting of the Chesapeake Section of the American Association of Physics Teachers.

Chandra Turpen, a physics assistant research professor who advises the MHTF, lauded the group’s ability to not only gather data but to effectively share their results with a larger audience.

“This team has consistently done top-notch work—gathering evidence, building relationships with stakeholders across these graduate programs, persuasively communicating their results and making requests to transform our graduate programs,” Turpen said. “Their work embodies many of the best practices for leading inclusive system change efforts.”

Going forward, the group hopes to recruit new students to MHTF—three of the five current members plan to graduate this year. Anyone interested in joining can email the group at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

And they hope to keep the momentum—and the conversation—going. Erin Sohr (B.S. ’10, physics and astronomy; Ph.D. ’18, physics), who co-founded the MHTF as a graduate student in 2016, said it has been meaningful to see the physics community rally around students’ mental health.

“I think the most important impact is around starting this conversation within the department, normalizing struggles and just making mental health something we notice and talk about together,” said Sohr, who is now a physics assistant research scientist at UMD.

Banner agreed, stressing the value of undertaking these surveys and having difficult conversations.

“Just having the conversation is a way of saying that mental health is a serious issue,” Banner said. “We don’t want to sweep this under the rug. We want everyone to be happy and healthy, so having these conversations is the first step to making that happen.”

Written by Emily Nunez