Quantum research involves many challenges, from building tiny intricate devices and interpreting the unintuitive microscopic world to grappling with unwieldy calculations. The community of quantum researchers also has to contend with societal issues, like the long-established racial and gender disparities in physics and trends that overhype or mystify quantum technologies.

As a quantum researcher, Kasra Sardashti, who joined the UMD Department of Physics in March as an assistant research professor and a principal investigator at the Laboratory for Physical Sciences (LPS), takes a practical, hands-on approach to problem solving. His research focuses on removing bottlenecks that limit the development of practical quantum devices. He’s also tackling another problem he believes is holding back quantum research: a lack of diversity in the researchers joining the field.

“I have a strong commitment to promoting diversity in STEM,” Sardashti said. “I've always found it surprising that there is such a significant underrepresentation of women and minorities in physics and engineering.”

According to data through 2021 from the American Physics Society, the American Institute of Physics and the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System, women received fewer than 22% of physics doctoral degrees annually in the U.S. And the five-year average of data through 2021 shows that while communities marginalized by race or ethnicity made up about 37% of the U.S. college-age population, members of those communities earned only 15% of the physics bachelor’s degrees and 8% of the doctoral degrees and held only 5% of physics faculty position.

Sardashti has seen colleagues from diverse backgrounds bring valuable new ideas and perspectives to the quantum research community—a field that is steadily growing. He wants to ensure it has a robust, diverse workforce to support its growing needs, and he doesn’t believe that getting more people into physics or math classes will be sufficient to get enough people working in the field. Getting people interested in quantum research often requires getting them past a discomfort with quantum physics, which Sardashti calls “quantumphobia.”

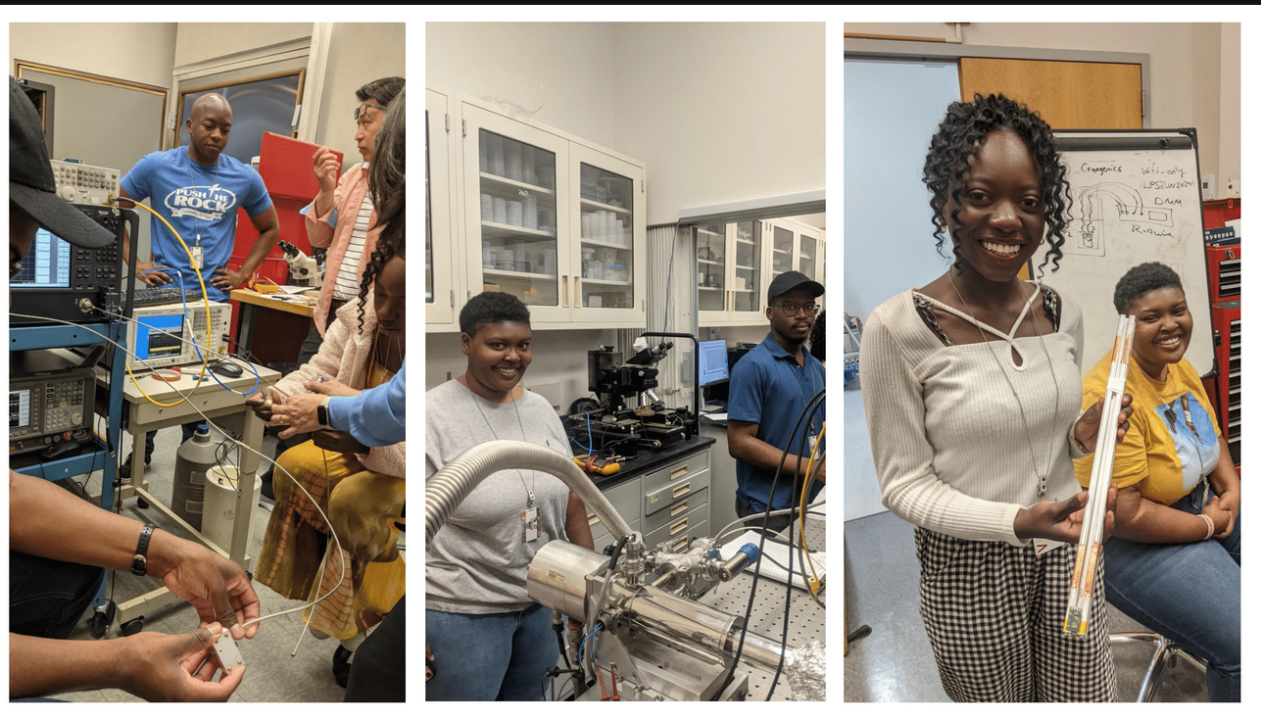

Sardashti believes the most effective way to counter quantumphobia is letting students perform experiments themselves so they can see the practical side of the field and have fun getting their hands on real projects. He decided to apply that approach in his efforts to attract students from underrepresented groups into the field. Last year, he and his colleagues started the Summer Quantum Engineering Internship Program (SQEIP) to give diverse groups of undergraduate students the chance to get their hands on equipment in real quantum research labs and gain practical experience with quantum engineering.

When Sardashti moved to UMD, SQEIP came with him. The facilities and researchers at the LPS Qubit Collaboratory and UMD’s Quantum Materials Center (QMC) created a new home for the program, and this summer they introduced 15 students to quantum research.

“I think that the part that drew me to science and engineering was actually doing things with my hands and getting a hands-on experience—experiential learning,” Sardashti said. “I think we should provide that to students. And this is how we jump started the program.”

Sardashti’s own path to quantum physics started from a practical, hands-on background. As a kid, he enjoyed working on things, like fixing computers and working on the wiring in the walls of his family’s home in Tehran.

Pursuing his practical interest, he attended Tehran Polytechnic where he studied materials engineering. Physics classes were required for the major, and the quantum physics ideas from the classes ensnared his imagination. So, he added extra physics courses to his schedule.

He continued studying materials science while pursuing his master’s degree at the University of Erlangen in Germany and his doctoral degree at the University of California, San Diego. During this time, his interest in physics attracted him to the intersection of material engineering and applied physics, and he studied the materials that make solar panels function. After that, he dove into quantum research as a postdoctoral researcher at the New York University Center for Quantum Phenomena and then as an assistant physics professor at Clemson University.

Now, Sardashti specializes in improving quantum devices and enabling new uses for the technology. His work includes studying how superconductor fabrication processes affect the resulting properties, designing voltage-tunable superconducting quantum devices, and proposing experiments to demonstrate non-Abelian statistics using quantum devices.

As Sardashti carried out his research, he kept noticing a lack of diversity around him and began searching for a way to address the issue. He decided he needed help to reach students who are underserved by the current system, so he began contacting professors at historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs) looking for someone interested in working with him. After several dead ends, John Yi, a chemistry professor at Winston-Salem State University (WSSU) responded, and they started collaborating.

“A lot of it was John's drive,” Sardashti said. “It's not that easy to go into an HBCU, pull a professor away from their four-course semester schedule, and be like, ‘Hey, can you just do something on the side?’ But he was willing to do it. He really wanted to get engaged. He's really passionate about training his students.”

Together Sardashti and Yi obtained funding from the National Science Foundation and the U.S. Department of Energy and launched SQEIP to give students, particularly those from underrepresented backgrounds, firsthand quantum engineering experience. The program gathered its first group of 11 students at Clemson University in summer 2023.

Yi is instrumental in running the program and takes a lead role in recruiting and selecting students from underrepresented backgrounds from both his own university and across the country.

SQEIP hit a road bump when Sardashti joined UMD in March, just a couple of months before the program’s second summer. Even though it was a tight schedule, Sardashti and Yi decided to relocate the program and take advantage of the experts and labs at UMD. In just a couple of months, they had to get local scientists and faculty to buy into the effort and agree to share their time, expertise and resources with visiting students. They also had to arrange student financial support, travel and housing. Fortunately, they connected with UMD Physics Professor and QMC Director Johnpierre Paglione, who helped run the program, recruit other colleagues and arrange for the students to work in QMC labs.

“After learning about SQEIP, I was delighted to participate by incorporating quantum materials training into the program,” Paglione said. “This was quite natural for us, since we run a condensed version each year as part of our Fundamentals of Quantum Materials Winter School, and QMC has the facilities to accommodate such a group.”

This year SQEIP included five students from WSSU and 10 students from nine other universities. Once the students arrived at UMD in May, they were split into two groups, which each spent three weeks at either QMC or LPS before swapping for another three weeks.

At QMC, the students explored how materials used in quantum devices are created and studied. For example, they used ultra-high-temperature furnaces and arc melting station (which can reach temperatures up to about 2,000 F and 3,600 F, respectively) to make their own crystal materials by carefully combining chemicals they had measured and mixed together. They were also trained to use techniques, like X-ray diffraction and X-ray fluorescence, to observe the structures of materials they had fabricated. They also measured the physical and magnetic properties of materials in very high magnetic fields and ultra-low temperatures.

“It’s really amazing to see students come into QMC without any experience and learn to synthesize novel materials like topological insulators and superconductors, all in a matter of a few weeks!” Paglione said. “Growing crystals is one of those things that’s fun and exciting, while also crucial to helping nurture a deep appreciation for the materials that will form the next generation of quantum devices.”

At LPS the students tackled several projects that introduced them to the basics of quantum device research. For instance, they dipped electric circuits into liquid nitrogen (which is below −321 F) to observe how the electrical conductivity changed with temperature. They then explored even colder temperatures using laboratory equipment, like a dilution refrigerator, which can produce temperatures less than a tenth of a degree above absolute zero. Extremely cold temperatures are often essential to getting quantum devices to function, and the students used the frigid conditions when measuring the properties of superconductors and microwave cavities, which play crucial roles in many quantum devices.

“I think the most beneficial part of the program is just the ability to utilize the resources that QMC and LPS had that you probably wouldn't get at your run-of-the-mill university,” said Taylor Williams, an information technology major at WSSU who participated in the program this year. “Working hands-on with the dilution refrigerator—that surprised me, just because it's so expensive. So, I was thinking we would tour it and look around, but I didn't think we'd actually get to play with it and analyze data off of it.”

By exposing the students to quantum engineering techniques, the program not only lets them connect with the field of quantum research but also provides them with context on how jobs in other fields might interact with or support quantum engineering. For instance, if participants end up going into chemistry and are producing new materials, their experiences during the program will provide insights into how those materials might be used in quantum devices.

“It's a great learning experience and a great way to start off with a lot of different options and different directions for where you want to go,” said Brenan Palazzolo, a physics major from Clemson University who participated in the program this year. “Any STEM major should apply. It was really an amazing program to have such a broad spectrum of students.”

The program wasn’t all work. Projects weren’t scheduled on the weekends, so participants had a chance to explore the area and see tourist sites like the White House, Smithsonian museums and the Lincoln Memorial in nearby Washington, D.C. Students also found time to have fun in the labs, like a group that used a microscope to get an up-close look at colorful flecks in rocks they had bought at a Smithsonian gift shop.

“I liked that we were really close to D.C.,” Palazzolo said. “It was kind of fun on the weekends and also really informative during the week. It wasn't just one thing that I was learning. I was learning the ins and outs of a lot of different parts of quantum research and the quantum processes for materials.”

Even after students return home, the program continues to provide advice to the participants and support their career progress. Alumni can request financial support to attend academic conferences where they can practice communicating about research, connect with scientists from other institutions, and get a sense of the broader opportunities available in the field. Alumni are also invited to apply for the following year’s program so that they can tackle more advanced projects using the techniques they learned the previous year.

“Johnpierre, myself, our leadership team at LPS, we actually believe in this,” Sardashti said. “I think this is a very good step—an important step—for people to get drawn to the field.”

Story by Bailey Bedford