University of Maryland Physics Professor Daniel Lathrop is making significant strides in tracking methane emissions on UMD’s campus and beyond.

In 2024, Lathrop and his team surveyed the stinky vapor plumes on the UMD campus caused by the university’s aging energy infrastructure for their Remediation of Methane, Water, and Heat Waste Grand Challenges project. With support from students, staff and faculty members across the university, Lathrop’s team helped pinpoint several key locations where excessive steam produced to power campus buildings escaped. Thanks to their efforts, the UMD community better understands the university’s energy production and consumption systems and environmental footprint and plans to use that information to remediate the systems.

Last month, Lathrop took the project to the skies to apply what he learned from his studies on UMD’s campus to address Maryland’s environmental challenges throughout the state. Excessive methane emission continues to be a major problem as populations grow, leading to air quality decline, increased atmospheric heat trapping, and heightened energy waste and costs.

“UMD’s campus represents a microcosm of urban and suburban environmental challenges that really have local, national and global implications,” said Lathrop, who holds joint appointments in the Departments of Physics and Geology, the Institute for Physical Science and Technology, and the Institute for Research in Electronics and Applied Physics. “Now that we have a better understanding of the problems our campus faces, we’re better equipped to tackle similar problems the rest of the state may have.”

“Prior research has shown that most American cities with an aging utility infrastructure lose a lot of methane to the atmosphere,” added Atmospheric and Oceanic Science Professor Russell Dickerson, who is a co-investigator on the project. “We need powerful new tools to locate, quantify and control these emissions. Field campaigns can provide benefits for the efficient use of energy and help protect the health of Marylanders.”

To accomplish this goal, Lathrop partnered with the Maryland Wing of the Civil Air Patrol, a U.S. Air Force auxiliary unit based near Baltimore County, Md. With pilot Piotr Kulczakowicz, who is also director of the UMD Quantum Startup Foundry, Lathrop conducted two research flights aboard the Patrol’s Cessna aircraft in February, hoping to accurately map methane emissions. Piotr Kulczakowicz and Dan Lathrop

Piotr Kulczakowicz and Dan Lathrop

“Just like how UMD came together to solve a problem that affects all the people living and working on our campus, we’re partnering with other members of our community to solve an issue that impacts the whole state,” Lathrop said. “As UMD faculty and as members of the Civil Air Patrol, Piotr and I were uniquely positioned to have UMD scientists team up with the Patrol in a relatively low-cost, efficient and mutually beneficial way of doing methane mapping compared to what many other researchers in this field have done. It’s the first time it’s ever been done here. We bring the instruments and expertise; they bring the planes.”

On the ground and in the air

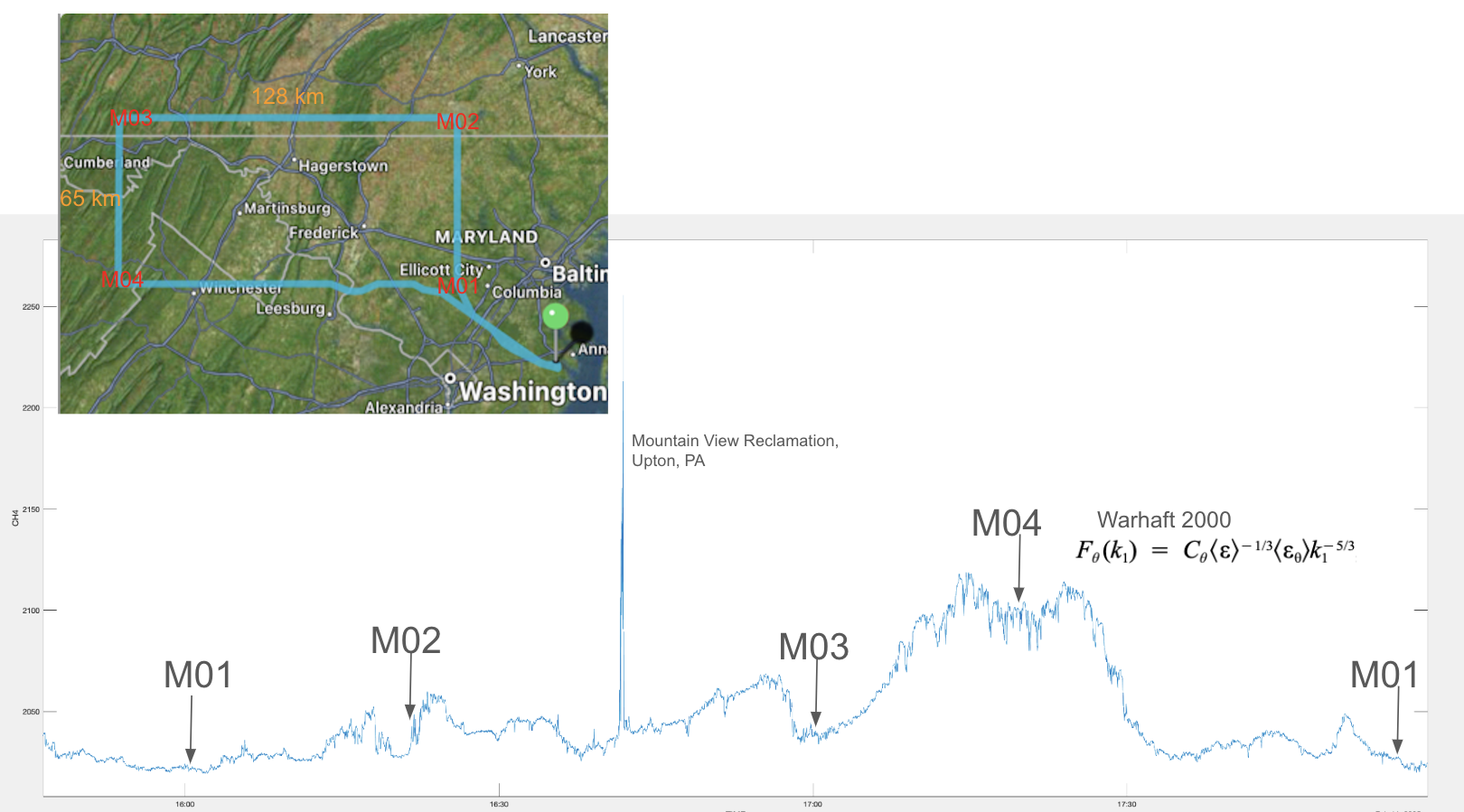

Lathrop’s first flight launched on February 10 from Annapolis, Md., circling around southern Pennsylvania and north central Maryland regions including Hagerstown. During this initial test flight, Lathrop focused on calibrating the instruments used to monitor methane—including a system called LI-COR, which is frequently used to track atmospheric changes. Strapped securely to a plane seat, the $30,000 optical sensor tracked real-time emission signatures in parts per billion, thanks to a two-meter-long tube attached to one of its ports and placed through a barely cracked plane window. Methane hot spots were easy to detect.

“It was very obvious whenever we flew past a methane hot spot,” Lathrop said. “We recorded a notable methane spike of more than 2,250 parts per billion while flying by what we later found out was a landfill in Pennsylvania called Mountain View Reclamation Plant. In contrast, we observed that flying over the Chesapeake [Bay] resulted in a sudden drop in methane levels, or well below 2,050 parts per billion, which we used as a baseline for distinguishing emission signatures from noise.’”

Lathrop’s second flight on February 24 yielded even more results. From the departure point near Fort Meade, Md., the plane executed two loops around the Baltimore region—one loop at a lower altitude of 1,700 feet and another at 2,700 feet for a more detailed picture of emission patterns near more populated urban areas. Lathrop (in the air) and later his team (on the ground) observed that cities tend to have correlated methane and carbon dioxide emissions, a distinct pattern that differs from other known sources like landfills or gas production facilities.

“Cities have cars and trucks that leak both methane and carbon dioxide, CO₂,” Lathrop explained. “On the other hand, gas facilities only produce methane and not much CO₂. Generally, landfills only produce methane and not CO₂. These differences could help stakeholders, especially the people living in these communities or who control these emission sources, address the leakages on a more individual level and better mitigate the issues—like high energy waste and costs—that come with them.”

Although his findings are in many ways unique to Maryland, Lathrop says that the methodology used on his flights could benefit other research teams in the region and other states interested in pinpointing methane emission sources and minimizing leakages. Lathrop is currently developing standardized procedures that will allow other teams to carry out similar missions in the future, with hopes that all stakeholde Methane readings.rs will be able to make better-informed decisions about their environmental impact.

Methane readings.rs will be able to make better-informed decisions about their environmental impact.

“We’re already planning for the next few flights across Maryland, which can be quite difficult considering our proximity to restricted airspace in D.C.,” Lathrop said. “But this is only part of a much bigger effort to reduce waste, reduce the associated environmental and fiscal costs, and protect our communities.”

###

Other UMD faculty members involved in the Remediation of Methane, Water, and Heat Waste Grand Challenges project include Environmental Science and Technology Associate Professor Stephanie Yarwood, FIRE Assistant Clinical Professor Danielle Niu, Geographical Sciences Assistant Professor Yiqun Xie, and Geology Associate Professor Karen Prestegaard and Professors Michael Evans and Vedran Lekic.