Pushing the Frontier of Extreme Light-Matter Interaction Research

- Details

- Published: Monday, February 08 2021 05:33

University of Maryland Physics Professor Howard Milchberg and the students and postdoctoral researchers in his lab explore the dramatic results of experiments that push light to extremes in the presence of matter. In Milchberg’s opinion, researching the intense interactions between light and matter—which are only possible thanks to the revolutionary technology of lasers—brings together the most interesting aspects of physics.

“Once you considered the effect that an intense laser beam has on matter, the number of basic physics and application areas exploded,” said Milchberg, who also holds appointments in the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering and the Institute for Research in Electronics and Applied Physics. “And understanding the interaction between intense light and matter requires bringing in tools from all areas of physics. It flexes all your physics muscles, experimental and theoretical, and it overlaps with all of the major areas. You have to deal with atomic physics, plasma physics, condensed matter physics, high-pressure physics and quantum physics. It is intellectually challenging and, as a bonus, it has many practical applications.”

In explorin Intense Laser-Matter Interactions Lab, University of Marylandg this research topic, his lab has discovered new physics and technological opportunities. From cutting-edge, powerful laser pulses to vortices made of light, recent research from Milchberg’s lab keeps revealing new ways that light and matter can come together and deliver new results.

Intense Laser-Matter Interactions Lab, University of Marylandg this research topic, his lab has discovered new physics and technological opportunities. From cutting-edge, powerful laser pulses to vortices made of light, recent research from Milchberg’s lab keeps revealing new ways that light and matter can come together and deliver new results.

The richness of this line of research comes from the fact that light is much more than just illumination traveling in straight lines at a constant speed. It is energy that can dance intricately as it travels and can interact with matter in exotic ways—including tearing atoms into pieces.

Light is traveling electric and magnetic energy, and it is often convenient to visualize light as traveling waves in the electric and magnetic fields. The hills and troughs in the waves represent the shifting of the strength and direction of the fields that push and pull on charged particles, like the protons and electrons that make up atoms. Powerful lasers can even accelerate charged particles to near the speed of light where the unusual behaviors described by Einstein’s theory of relativity come into play.

Milchberg’s lab often investigates the dramatic results of dialing a laser up to extreme strengths where it exceeds the field that connects the cores of atoms to its electrons. As researchers like Milchberg push lasers to greater and greater power levels, they reach a roadblock: A laser tends to spread its power out over an increasing area as it travels, and a laser with enough power will vaporize any solid piece of equipment that researchers try to use to corral it.

So an optical fiber, like those that commonly carry internet signals, are useless when faced with a powerful research laser. The central core and outer cladding that make up the fiber get destroyed without any chance to keep the light concentrated as it blazes forward.

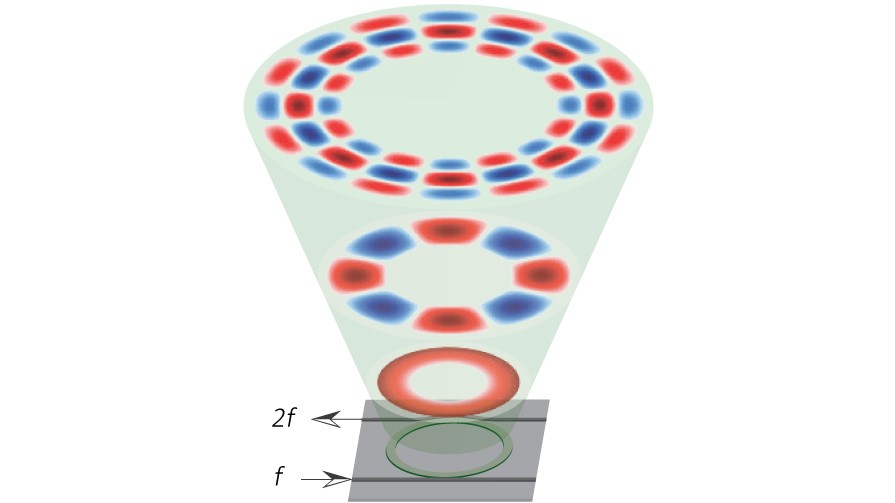

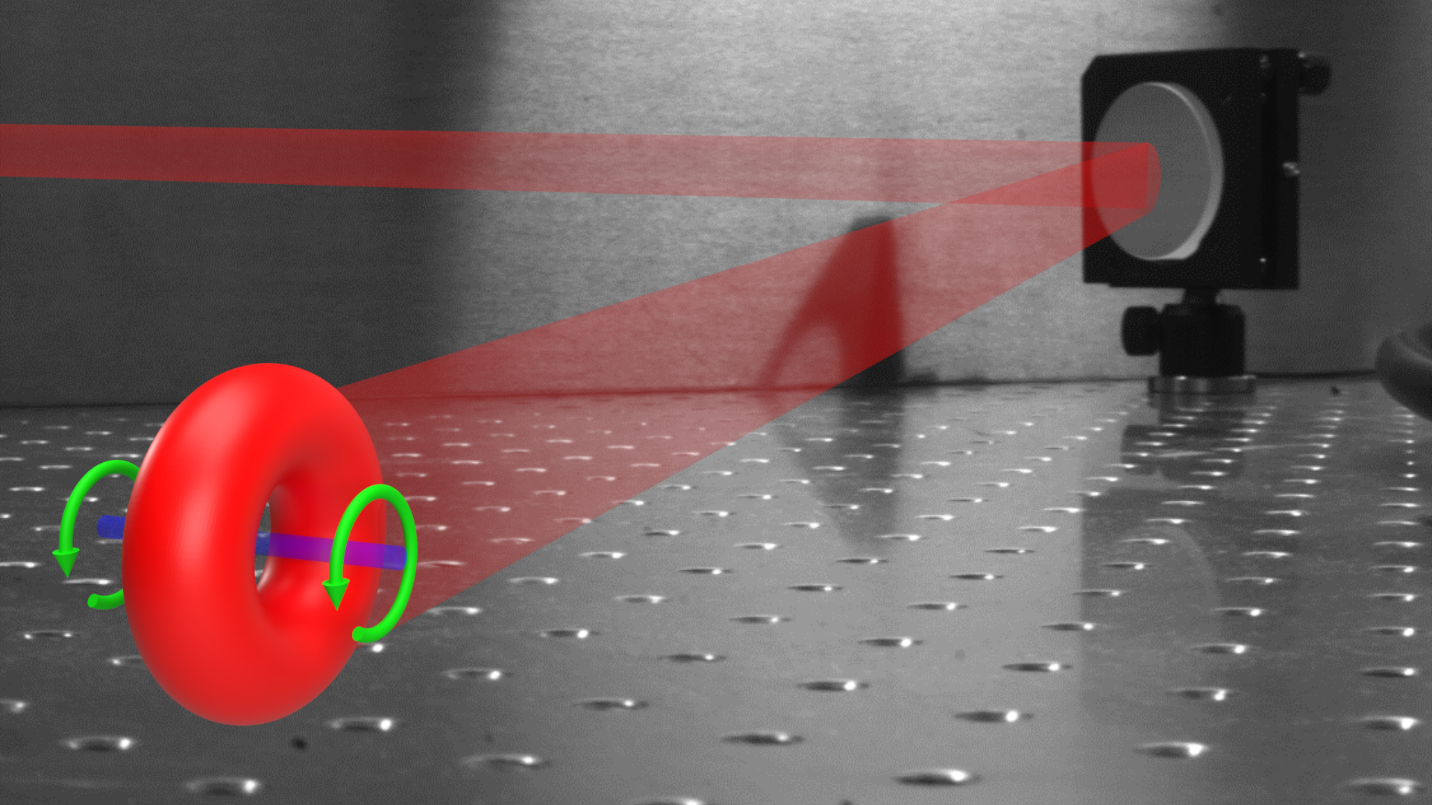

But Milchberg’s research has uncovered multiple ways to use the interactions of light with matter to keep powerful laser beams contained. In papers published in the journals Physical Review Letters and Physical Review Research over the past year, Milchberg and his colleagues described two new ways to keep intense laser beams contained in a way that can accelerate particles and produce advanced coherent light sources. In addition to improving our understanding of how light and matter interact, the techniques might be implemented as tools for research in other areas, like high-energy physics, and for use in industrial and medical settings. Researchers have generated vortices of light that they describe as “edge-first flying donuts” and developed a new technique for imaging them in mid-flight. (Credit: Scott Hancock/University of Maryland)

Researchers have generated vortices of light that they describe as “edge-first flying donuts” and developed a new technique for imaging them in mid-flight. (Credit: Scott Hancock/University of Maryland)

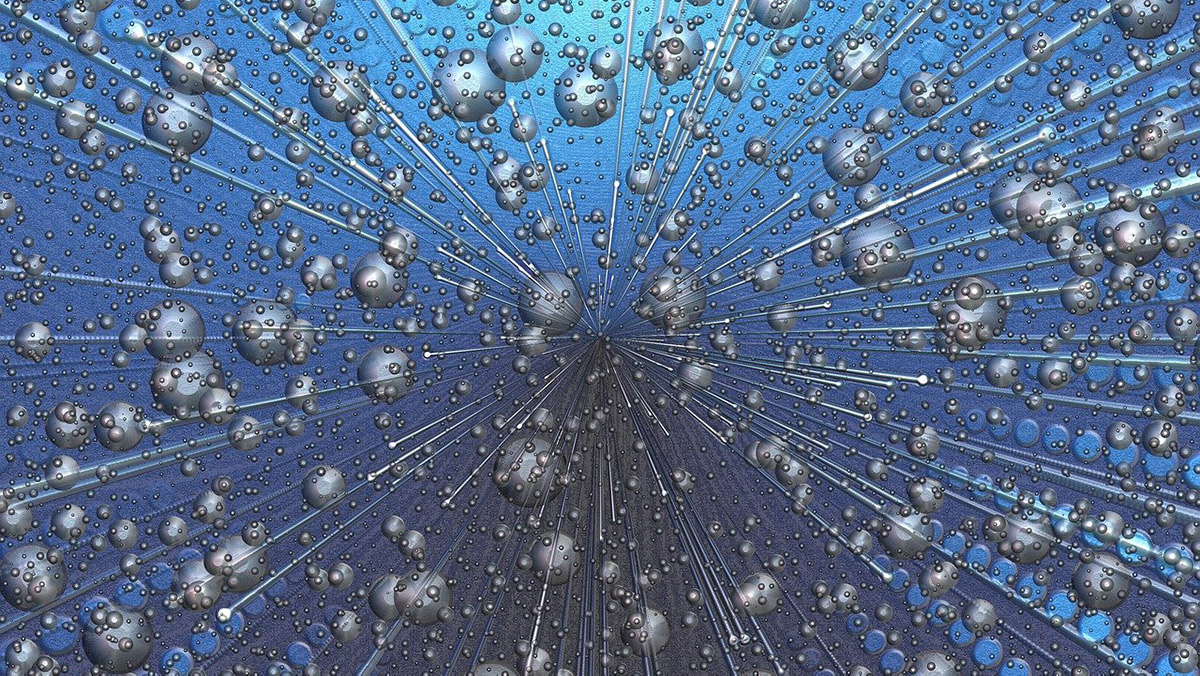

In these projects, the group used its expertise to give the technology of optical fibers an extreme indestructible makeover. The key lies in building the waveguides—devices such as optical fibers that transport waves down a confined path—out of a material that has already been vaporized. The team forms the material—an energetic state of matter called a plasma—by letting a laser rip electrons free from their atoms to form a cloud of charged particles.

“A plasma waveguide has all the structure of an optical fiber, the classic core, the classic cladding,” Milchberg said. “Although in this case, it's indestructible. The hydrogen plasma forming the waveguide is already ripped up into its protons and electrons, so there's not much more violence you can do to it.”

For the first project, the group used two laser pulses: a solid beam and then a hollow tube of light matching the desired form of the outer shell. These two lasers allowed the team to independently craft the low-density cores and outer shells more carefully than previous approaches. This refined control improved the amount of power the techniques could concentrate and the distance the powerful pulses could travel—a key to achieving desired levels of acceleration with a compact system.

The second approach produced a similar plasma waveguide but sacrificed the ability to tailor the resulting waveguide in favor of using a simpler, more accessible technique. In this technique, the researchers created a tube of low-density gas and then relied on the front edge of the powerful pulse to rip the electrons free and create the waveguide structure on-the-fly.

“It's actually simpler than the first method,” Milchberg said. “But there's less control. And we did an analysis which shows that if you want to have big diameter waveguides, the first method is actually more efficient than the second method.”

Both methods have potential uses as laser accelerators that can generate bursts of electrons of energy 10 billion electron volts, and Milchberg’s group is already doing those experiments.

In addition to these two techniques, Milchberg’s group is developing a technique that uses a 1,000 times higher density hydrogen gas to accelerate electrons without constructing a waveguide, while using 1,000 times less laser energy. This new technique improves on established methods by avoiding negative effects from the light vibrating the electrons as they get accelerated behind the intense laser pulse.

To do this, they used pulses of circularly polarized light that aren’t even as long as two full lengths of the waves of the light that is used. The field of circularly polarized light rotates as the light travels and this variation cancels out the effect of the asymmetries of the vibration from the light waves, enabling electron beams of higher quality than previous attempts. The denser gas used in this approach isn’t compatible with the 10 billion electron volt energies of the other approaches, but the technique might have its own niche to fill.

“Our experiments have spanned the higher through lower energy ends of laser-based acceleration,” Milchberg said. “The plasma waveguide effort is aimed at 10 billion electron volts, which is of high energy physics interest, while the newer research using millijoule pulses and dense hydrogen generates 15 million electron volts. Although a high energy, it isn’t enough for high energy physics. But the energy is more than sufficient to do time-resolved medical imaging and materials imaging.”

But accelerating particles is not the only aspect of light-matter interactions that Milchberg’s group investigates. For instance, they also discovered new intricate effects that can be created in light pulses.

In a paper published in the journal Optica in December 2019, they generated and observed a new kind of light structure called a spatiotemporal optical vortex (STOV). STOVs are whorls in the way the phase—the property of light and other waves that tells you are where you are on the wave—changes in space and time. The researchers had to first develop a method to create these vortices and then figure out how to observe them in flight. The observation required analysis of the interaction between the STOVs and another bit of light while traveling through a thin glass window.

Understanding STOVs provides insight into how light produces the high-intensity laser effect called self-guiding. Milchberg’s team had previously discovered a naturally occurring form of STOV that behave like “optical smoke rings” and are crucial for all self-guiding processes. These vortices may also have applications in transmitting information because the twisting structure tends to stabilize itself by filling any sections that get knocked out—say by water droplets in the air that the signal travels through.

All of these research results represent new techniques that may be useful tools for researchers and industry, and they deepen our understanding of the intricate back-and-forth that can be engineered between light and matter.

“One of the things that I would say my group is known for is that all of our papers include theory and simulation that accompanies the experiments,” Milchberg said. “And that has provided an important feedback loop to guide and refine the experiments.”

Milchberg credits his group’s steady generation of new discoveries to his graduate students.

“I don't think I could have done any of this in a non-university setting,” Milchberg said. “I think the sort of relationship one has with students and they have with each other where we're all batting ideas back-and-forth and having a continuous free-for-all discussion—with crazy thoughts encouraged—is not the same as in a place filled with longtime Ph.D.s and an established hierarchy. The freedom to ask naïve questions and argue a lot is essential.”

Written by Bailey Bedford