Sometimes, what seems like a fantastical or improbable chain of events is just another day at the office for a physicist.

In a recent experiment by University of Maryland researchers at the Laboratory for Physical Sciences, a scene played out that would be right at home in a science fiction movie. A tiny speck glinted faintly as it hovered far above a barren, glassy plain. Suddenly, an intense green light shone toward the ground and enveloped the speck, now a growing dark spot like a meteorite or UFO descending in the emerald beam. Once the object crashed into the ground, the light abruptly disappeared, and the flat landscape was left with a new landmark and treasure for physicists to find: a chunk of gold rapidly cooling from a molten state.

This scene, which played out at a minuscule scale in repeated runs of the experiment, was part of a research project on nanoparticles—objects made of no more than a few thousand atoms. Each piece of gold was a bead hundreds of times smaller than the width of a human hair. In each run, the golden projectile was melted by a green laser and traveled almost a million times its own length to land on a glass slide.

Nanoparticles interest scientists and engineers because they often have exotic and adaptable properties. Unlike larger samples of a material, a nanoparticle can undergo dramatic changes with only small tweaks to its environment or size. For instance, a tiny gold nugget in a California stream has the same melting point, reflectivity and thermal conductivity as a 400-pound block of gold in Central Park, but two gold nanoparticles that differ in diameter by mere billionths of a meter have significantly different properties from the large pieces and, more importantly, each other.

The broad range of properties that nanoparticles have makes them a versatile toolbox for researchers and engineers to draw from. For example, people have used gold-based nanoparticles to detect the influenza virus, deliver medications in the body, and achieve a variety of vibrant colors in stained glass. However, since nanoparticles are so small and easily influenced, researchers must use a variety of specialized tools to study them.

When examining nanoparticles, some properties are best measured by tools—like a scanning electron microscope (SEM)—that get up close and personal with the sample. An SEM can get phenomenal detail on the size and shape of a nanoparticle if it is attached to a larger material that is easy to move and handle. However, the small size of nanoparticles can make other properties, like how they conduct heat, almost impossible to measure if they are touching anything. The mere presence of larger objects can often alter a nanoparticle’s properties or drown out its interaction with the measurement device. Fortunately, many nanoparticles can be isolated from the influence of other materials by using electric fields to levitate them, allowing researchers to use lasers to study certain properties, like heat conduction, from a distance.

JQI Fellow Bruce Kane and UMD researcher Joyce Coppock perform levitation experiments to study tiny pieces of graphene, which are sheets of carbon atoms. And in their quest to develop new tools, they have also turned their attention to tiny gold beads.

However, Kane and Coppock aren’t satisfied with the insights available from levitation experiments alone. They want the best of both worlds: to measure a sample levitated in isolation and then recover it for direct inspection. So, the pair are developing a method to recover tiny samples after they are released from the fields levitating them. In a paper published in Applied Physics Letters, the pair described how they were able to deposit gold nanoparticles on a slide after levitation and how they refined the technique to hone their aim. They hope mastering the process with gold will be useful in future experiments depositing more finicky graphene samples.

Before experimenting with depositing gold, Kane and Coppock had initially tried depositing graphene nanoparticles. Levitation is important for studying graphene on its own because its thickness—just a single atom—makes it challenging to study certain properties when it’s sitting on top of another material. For instance, a bulky material under a piece of graphene generally retains or moves heat around much more dramatically than the graphene, overwhelming any attempts to measure the heat conduction of the graphene itself. Additionally, simply sitting atop another material is often enough to stretch or squeeze a graphene sample in ways that change important properties, like its electrical resistance.

To avoid these issues, Kane and Coppock typically levitate their graphene samples in a vacuum. But the properties best measured directly without levitation are required to get a complete picture of a nanoparticle.

Ideally, Kane and Coppock would like to do both styles of measurement on individual nanoparticles. However, the existing levitation procedure makes it impractical either to perform direct probes on a sample before levitating it or to recover a sample once they remove the electric fields. That’s because there isn’t a convenient way to select a single tiny particle and reliably drop it into the field or recover it from the field.

In their experiments, Kane and Coppock first create an electric field designed to capture charged particles inside a vacuum chamber. To levitate a sample, they fill the chamber with many charged nanoparticles and watch to see if one of them falls into the field. After they make their measurements of that lucky particle, it gets released and becomes just another anonymous, invisible nanoparticle scattered about the vacuum chamber.

But Kane and Coppock had an idea for how to recover samples. Instead of just dropping the electric field and letting the particle fly in a random direction, they realized they could adjust the field to give it a shove in a particular direction as they released it. Then they just had to see if they could get the tiny projectile to land in an area they could easily search.

The pair placed a removable glass slide coated with a thin, conductive layer in the chamber as their target. Connecting a charge sensor to the conducting film allowed them to detect if an electrical charge landed on the slide. They also pointed a camera at the slide. The camera couldn’t watch the nanoparticles as they traveled, but each nanoparticle is just large enough that it will normally show up as a change of a single pixel in the camera image.

The pair’s calculations suggested that if a graphene sheet lands flat on the prepared slide it should stick. However, when they tried out the experiment, they kept measuring a spike in charge at the target—suggesting it hit—but almost never spotted where the sample landed. They suspected that most samples were bouncing off the slide or landing outside the area their camera covered.

So, they simplified the experiment by switching their projectile. Instead of using sheets of graphene that need to land perfectly flat, they tried spherical gold nanoparticles, which can be more uniformly produced and don’t have a preferential orientation for making contact. Kane and Coppock were already familiar with working with gold nanoparticles from previous experiments in which they levitated them and melted them with laser light.

Similar to the graphene sheets, the gold spheres were detected by the charge sensor but then couldn’t be found in the camera image. So, Kane and Coppock applied their melting technique to allow each particle to squish a little when it lands, greatly increasing the chance of sticking. All that was required to melt the gold was to turn up the power on the laser they already had installed for studying samples.

“Lo and behold, the minute we started doing that, we started seeing images on the camera,” says Coppock. “So basically, what was needed was to increase the adhesion by melting the particle.”

After that, they could reliably find the particles. However, repeated tries revealed that a sequence of deposited samples tended to spread far apart on the slide. Being able to place a sample in a consistent area would make the technique more useful and increase their chances of finding deposited graphene samples down the road.

“It's like the problem that people have going to the moon, right?” says Coppock. “You're a tiny person on Earth, and you have to get yourself a long distance to the moon. If you just launched yourself off the Earth, there's no way you would hit the moon. If we just launched the particle out of the trap, there's no way it would both hit the substrate and we would know where it was on the substrate. Finding a 200-nanometer particle on a one-inch sized substrate is like finding a needle in a haystack.”

So, they started working on the consistency with which they launched their tiny samples. The same electrical charge that allows Kane and Coppock to levitate the particles, also allows them to guide particles on the way to the slide. They surrounded the path they wanted the nanoparticles to follow with metal rings and then applied a voltage to the rings during the journey. The applied voltage creates an electric field that nudges a nanoparticle back onto a narrower path if it starts to stray. The way the electric fields bend charged particles back to a central focal point resembles a glass lens focusing light, so researchers call the setup an electrostatic lens.

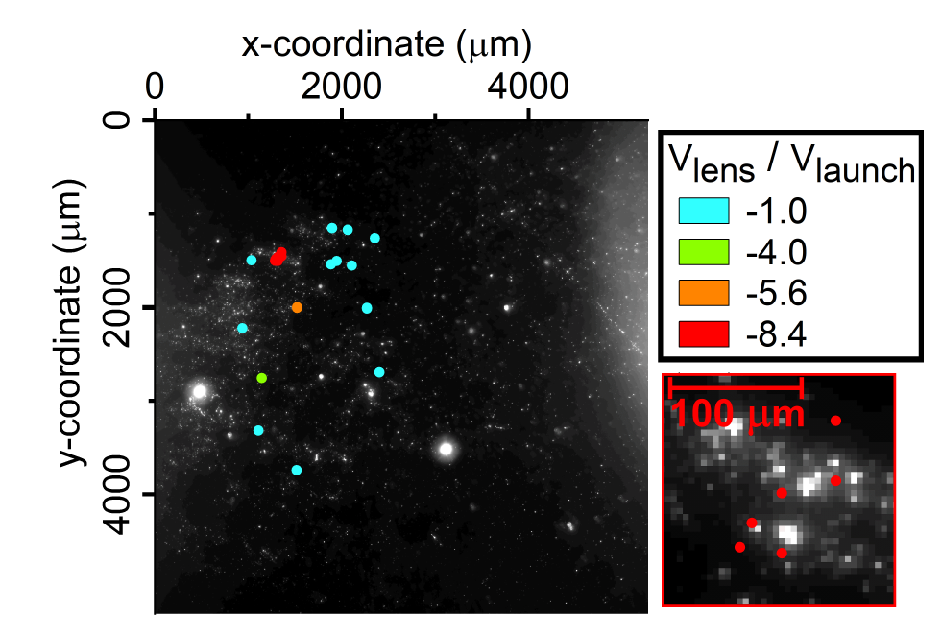

By experimenting with the voltages that they used to launch the sample and guide it along its path, they were able to change where the particles tended to end up. They adjusted the voltages from a low setting where the samples spread over an area roughly 3,000 micrometers wide to a higher setting where all the particles clustered in an area about 120 micrometers across.

Plots of where gold particles from repeated runs of the experiment landed. The colors of the dots reflect the voltages applied to achieve electrostatic lenses of various strengths. The weakest lens (light blue dots) spread the samples across an area that is about 3,000 micrometers wide, and the strongest lens (red dots) focused all the particles into a cluster just 120 micrometers across. The lower right frame has increased magnification to show the distribution of particles within the cluster created by the strongest lens. (Credit: Laboratory for Physical Sciences)

Plots of where gold particles from repeated runs of the experiment landed. The colors of the dots reflect the voltages applied to achieve electrostatic lenses of various strengths. The weakest lens (light blue dots) spread the samples across an area that is about 3,000 micrometers wide, and the strongest lens (red dots) focused all the particles into a cluster just 120 micrometers across. The lower right frame has increased magnification to show the distribution of particles within the cluster created by the strongest lens. (Credit: Laboratory for Physical Sciences)

If the initial scatter area were scaled up to the size of a dartboard, then their improved aim was like clustering their golden darts well within the outer bullseye. This is even more impressive since the scaled-up version of each gold bead is a dart only as wide as a human hair and is being thrown from the equivalent of about 35.5 meters away—about 15 times the normal distance between a dartboard and the throw line.

Moving forward, Kane and Coppock hope to further improve their ability to focus samples into a particular area and to use their refined aim in attempts to recover deposited graphene samples.

Original story by Bailey Bedford: https://jqi.umd.edu/news/researchers-play-microscopic-game-darts-melted-gold