Our computer age is built on a foundation of semiconductors. As researchers and engineers look toward a new generation of computers that harness quantum physics, they are exploring various foundations for the burgeoning technology.

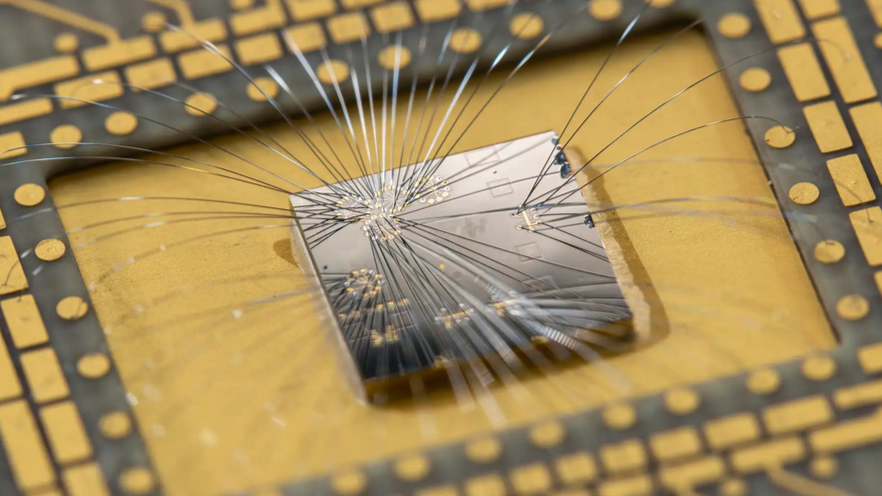

Almost every computer on earth, from a pocket calculator to the biggest supercomputer, is built out of transistors made from a semiconductor (generally silicon). Transistors store and manipulate data as “bits” that can be in one of two possible states—the ones and zeros of binary code. Many other things, from vacuum tubes to rows of dominos, can theoretically serve as bits, but transistors have become the dominant platform since they are convenient, compact and reliable. Researchers have been working to demonstrate that devices that combine semiconductors and superconductors, like this one made by Microsoft, have the potential to be the basis for a new type of qubit that can open the way to scalable quantum computers. (Credit: John Brecher, Microsoft)

Researchers have been working to demonstrate that devices that combine semiconductors and superconductors, like this one made by Microsoft, have the potential to be the basis for a new type of qubit that can open the way to scalable quantum computers. (Credit: John Brecher, Microsoft)

Quantum computers promise unprecedented computational capabilities by replacing bits with quantum bits—qubits. Like normal bits, qubits have two states used to represent information. But they have additional power since they can simultaneously explore both possibilities during calculations through the phenomenon of quantum superpositions. The information stored in superpositions, along with other quantum effects like entanglement, enables new types of calculations that can solve certain problems much faster than normal computers.

All quantum objects sometimes enter a superposition, but that doesn’t mean they all make practical qubits. A qubit needs certain traits to be useful. First, it must have states that are easy to identify and manipulate. Then, the superposition of those states must last long enough to perform calculations. Physicists typically think about the stability of a quantum state in terms of its coherence, and how long a quantum state can remain coherent is a critical metric for judging its suitability as a qubit.

So far, no platform has emerged as the default for making qubits the way silicon-based transistors did for bits. As researchers and companies build the early generations of quantum computers, many options are being used, including superconducting circuits, trapped ions, and even particles of light.

Some researchers, including Professor and JQI Fellow Sankar Das Sarma and Professor and JQI Co-Director Jay Sau, have been exploring the possibility that semiconductors might prove to be a good foundation for quantum computing as well. In 2010, Das Sarma, Sau and JQI postdoctoral researcher Roman Lutchyn proposed that a strong magnetic field and a nanowire device made from the combination of a semiconductor with a superconductor could be used to create a particle-like quantum object—a quasiparticle—called a Majorana. Nanowires hosting Majorana quasiparticles should be able to serve as qubits and come with an intrinsic reliability enforced by the laws of physics. However, no one has definitively demonstrated even a single Majorana qubit while some quantum computers built using other platforms already contain more than 1,100 qubits.

Fifteen years after Das Sarma and Sau opened the door to experiments searching for Majorana quasiparticles, they are optimistic that the proof of Majorana-based qubits is now on the horizon. In an article published on June 18 in the journal Physical Review B, Das Sarma and Sau used theoretical simulations to analyze cutting-edge experiments hunting for Majoranas and proposed an experiment to finally demonstrate Majorana qubits.

“I think that we're at the point where we can at least see where we are in terms of qubits,” says Sau, who is also professor of physics at UMD. “It might still be a long road. It's not going to be easy, but at least we can see the goal now.”

The Tortoise and the Hare?

Since quantum computers are already being built from other types of qubits, Majoranas are behind in the race. But they have some advantages that proponents, including Das Sarma and Sau, hope will let them make up for lost time and become the preferred foundation for quantum computers.

One advantage Majorana qubits potentially have is the extensive infrastructure that already exists around semiconductors. The established knowledge and fabrication techniques from the computer industry might allow large quantum computers with many interacting qubits to be built using Majoranas (which is a goal all the competition is currently working to achieve). If Majorana-based quantum computers prove easier to scale up than their competition that might allow them to make up for lost time and be a competitive technology.

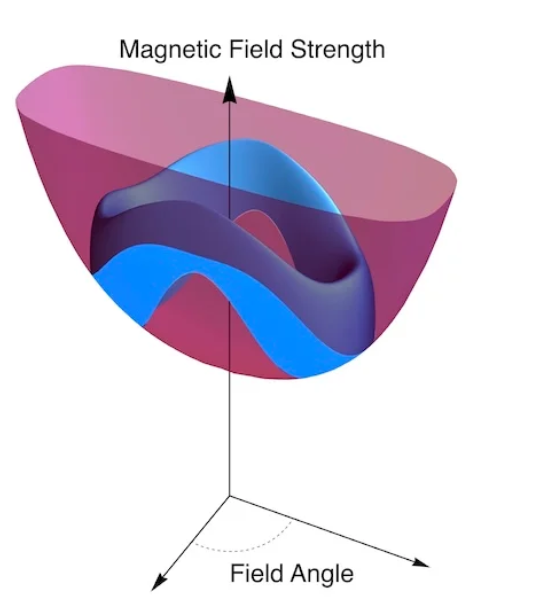

But the thing that really sets Majorana qubits apart from the competition is that their properties should protect from errors that would derail calculations. In general, the superpositions of quantum states are easily disrupted by outside influence, which makes them useless for quantum computing. However, Majorana quasiparticles are a type of topological state, which means they have traits that the rules of physics say can only be altered by a dramatic change to the whole system and are impervious to minor influences. This “topological protection” might be harnessed to make Majorana qubits more stable than their competition.

Pursuing these potential advantages, Microsoft has been trying to develop a Majorana-based quantum computer, and in February of this year, Microsoft researchers shared new results in the journal Nature where they described their observations of the two distinct quantum states of their device designed to create Majorana quasiparticles. At the same time, they also announced additional claims of having Majorana-based qubits, which has sparked controversy. In July, Microsoft researchers posted an article on the arXiv preprint server that elaborates on their claims of creating a Majorana qubit using their device. They observe results consistent with creating a short-lived Majorana qubit, but they acknowledge in the article that the type of experiment they performed cannot prove that Majoranas are the explanation.

The experiment described in the Nature article opened new measurement opportunities by introducing an additional component, called a quantum dot, that connects to the nanowire. The quantum dot serves as a bridge that quantum particles can travel across but never stop on—a process called quantum tunneling. This development allowed them, for the first time, to hunt for Majorana quasiparticles that might be useful in making qubits. Their experiment demonstrated that they could observe two distinct states where they expect Majoranas to reside in the device, which hints at the necessary ingredients of a qubit, but didn’t prove that Majorana quasiparticles were successfully created.

In their new article, Das Sarma and Sau analyzed Microsoft’s published data and found that the measurements described in the paper could not prove if they had an ideal Majorana quasiparticle with its guaranteed stability or if the presence of impurities in the device resulted in imperfect Majoranas that produce only some of the signs of a topological state. The imperfect Majoranas could still offer some improved stability but don’t carry the ironclad guarantee of topological protection. Even if the device didn’t hold ideal Majoranas, it still might be able to function as a qubit with useful properties.

“We were excited that they're now actually getting into a qubit regime,” Sau says. “One of the things we wanted to do in our analysis is be agnostic to whether it's Majoranas or not. You have this device. Let's just ask ‘What kind of a qubit coherence would one get from a qubit made out of this device?’ And that's really the important question in this field.”

The Road Forward

To investigate the coherence of potential Majorana qubits, Das Sarma and Sau created a basic theoretical model of Microsoft’s device and used it to simulate nanowires that harbored various amounts of disorder—disorder that might disrupt the formation of Majoranas. Their simulations indicate that Microsoft’s device is likely plagued by a level of disorder that would prevent it from having a competitively long coherence time. However, the simulations also indicate that if enough disorder is eliminated then the device could see a dramatic jump in how long it maintains its coherence. A clear measurement of coherence is likely to be the smoking gun that leads many researchers to accept that a Majorana qubit has been fabricated.

As researchers attempt to demonstrate the coherence of a Majorana qubit, there are two ways they can respond to the presence of disorder in their devices: eliminate it or work around it.

In the article, Das Sarma and Sau used their simulation to describe experiments that require devices with fewer defects and that could clearly demonstrate the coherence of the Majorana quasiparticle. The experiment would require researchers to use two nanowires that can each contain a Majorana and that are connected via quantum tunneling. The tunneling would allow researchers to create a superposition where the Majorana is in a mixture of the two possible locations. When there is a superposition between the two states, the researchers can make the probability of the Majorana being in each spot oscillate so it goes from more to less likely in each location. This back and forth is predicted to provide a clear sign of how long the quantum state remains coherent but requires work in improving the nanowire quality to achieve the results.

The pair also discussed an alternative approach using simpler experiments that are similar to the one published in Nature. This approach continues to focus on measuring if a particle exists in a particular wire. The simulations Das Sarma and Sau performed suggest that if the measurement techniques were improved sufficiently the technique could give an estimate of the coherence, but it will be trickier to pick out the signature from the noise than using their proposed experiment. And the effort improving the measurement would likely not translate into making the nanowire into a Majorana qubit with a competitive coherence time.

“We can now start to see the finish line,” Sau says. “The experiments don't tell us quite where we are; that's where simulations are useful. It’s telling us that disorder is one of the key bottlenecks for this. There are various options of which path you can take, and the harder and more rewarding path is to just work on improving disorder.”

Original story by Bailey Bedford: jqi.umd.edu/news/researchers-spy-finish-line-race-majorana-qubits

-

Capacitance-based fermion parity readout and predicted Rabi oscillations in a Majorana nanowire , J. Sau, and S. Sarma, Phys. Rev. B, 111, 224509, (2025)