From Physics to Finance

- Details

- Published: Wednesday, February 04 2026 01:40

For Nathan Frohna (B.S. ’22, physics, MQF ’25, quantitative finance), an undergraduate degree in physics from the University of Maryland opened the door to business school, a master’s degree and an unexpected detour—from science to the financial world.

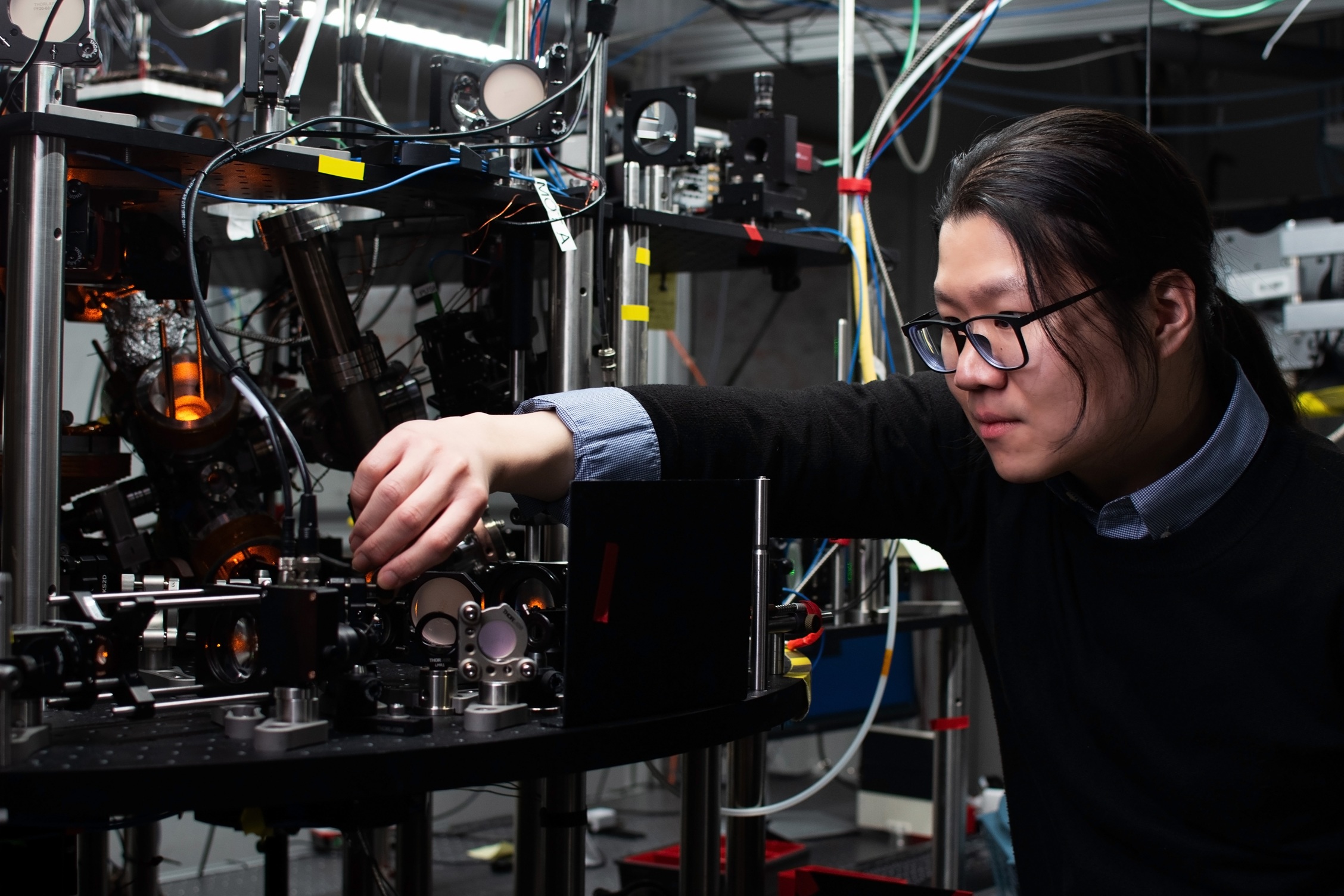

“When I was starting college at UMD, I can honestly say that I thought I’d always stay in physics research and academia. Finance was not on the radar,” Frohna said. “But I have come to appreciate that just as physics governs our universe, business and finance govern the world we live in and interact with, and solving the problems, complexities and challenges in that field can be just as rewarding. I feel very good about my path.” Nathan Frohna

Nathan Frohna

Frohna’s path may have shifted toward finance, but he didn’t leave physics behind. Now working as an associate on the financial risk and assessment team at Morgan Stanley in Baltimore, he discovered that many of the skills he learned and applied in physics—tools like critical thinking, complex problem-solving, programming and analytical thinking—are invaluable to his work in finance as well.

“I’m still quite new in my current role, but so far, the things that are important in my day to day work now—having an intuition with statistics and logical processes, the ability to persevere working through long, complex problems, and the instinct to always develop a mental understanding of all the variables and unknowns—are skills that I honed from years of studying physics,” Frohna explained. “Solving puzzles in the financial world has lots of interesting rewards, benefits and consequences that I didn’t really see with physics, but many of the problems are remarkably similar.

Puzzles waiting to be solved

Frohna has always looked at the world around him as an endless array of puzzles waiting to be solved.

“Even as a kid, I was all about trying to understand the reality around me, and that kind of led me to pick physics as my main interest, my passion and eventually my major for undergrad,” Frohna said. “There’s just something about being able to quantify the world around me. I love the problem-solving.”

Even before he started studying physics in college, Frohna took a deep dive into physics videos on YouTube.

“I think that through the years, that’s where I’ve gotten probably 90% of my physics knowledge, just finding interesting physics topics and diving into them,” he said. “Watching those videos, just kind of stumbling down different rabbit holes online, would give me the same enjoyment as playing video games or hanging with friends. There was always so much more to learn.”

As a physics major at Maryland, Frohna embraced every challenge, from thermodynamics to quantum mechanics, the tougher the better.

“I would say quantum was where the intuition that drove me through physics just failed for me, because you have to think about it completely differently,” Frohna recalled. “That was where I was struggling the most, but at the same time, it was the most fun challenge that I’ve had academically. It was really inspiring. I felt like if you can tackle something like that, you’re pretty much golden. You can do anything.”

A bridge to the future

Though Frohna loved physics, he couldn’t help wondering how it would fit into his future career plan. During his senior year, his UMD business student girlfriend convinced him to join her team for the Impact Competition, where student teams pitch innovative projects and compete for funds to advance their work. For Frohna, the experience was life-changing.

“I took over as the analytics guy, the numbers guy for the team’s pitch, and I think that’s when I realized that the way I was taught to solve problems in physics at Maryland is extremely translatable to business and finance,” he said. “It helped me see in a very meaningful way how physics could be a bridge to that world.”

Inspired by the discovery, Frohna went on to earn his master’s degree in quantitative finance at UMD’s Robert H. Smith School of Business, where he saw an even stronger connection between physics and finance.

“I learned there are plenty of equations in finance that look remarkably similar to physics equations,” Frohna explained. “For example, Brownian motion--the random motion of particles suspended in a medium, and the mathematics that describe how the system evolves with respect to diffusion--and the Black-Scholes model, which is a mathematical model for the dynamics of a financial market, are incredibly similar.”

Now, in his work at Morgan Stanley, Frohna leverages his physics skill set to help the company meet regulatory standards and manage risks in its day-to-day operations.

“I work on financial regulatory reporting, testing financial IT SOX controls for our annual Form 10K filing,” he said of his work measuring the accuracy and integrity of financial reporting. And I feel my physics background suits me well, as each control I test involves systems and software that I am unfamiliar with,” he said. “Trying to understand and develop theories for where risk may arise in these processes always comes down to logic, evoking the same skills I needed when I was facing unfamiliar classical thermodynamics problems in physics.”

Frohna hopes that as he gains more experience, his work will take him even deeper into quantitative finance.

“I’d like to get to a place where I’m really challenged, just like I was with quantum mechanics, because if I can get to a place where I can work on problems that push me to my limit, that’s where I can get the most out of it,” he explained. “What’s great about being at Morgan Stanley is that it’s so big, and they promote moving up and moving around within the company, so this is a great place for me to grow.

For Frohna, it’s all about applying his physics knowledge in a way that makes a difference. And he couldn’t be more grateful for the degree that started it all.

“I like mentioning to people that I have a degree in physics from Maryland, even before I mention quant finance. It’s something I’m really proud of,” Frohna said. “Physics taught me so much about deep analytical, challenging problems and what you can accomplish when you try not to get too overwhelmed, and you just keep putting in the effort. My physics degree opened doors I didn’t expect, and I think it’s the most valuable thing I’ve ever done for myself.”

Written by Leslie Miller