A big part of research is working with other scientists. As an undergraduate and graduate student at the University of Maryland, Jacob Bringewatt (B.S. ’18, physics) put in the work knocking on doors and connecting with professors, which allowed him to explore a broad range of research projects and earned him accolades along the way. Jacob Bringewatt

Jacob Bringewatt

Bringewatt was torn deciding between a small liberal arts college and a bigger state university for college. He came to UMD to interview for a Banner/Key Scholarship and during the visit he spoke with Physics Professor Tom Cohen. Cohen emphasized that a strong research program—like the one UMD has—is an important component of a high-quality physics education. That conversation—and receiving the scholarship—pushed UMD to the top of Bringewatt’s list, and he enrolled in 2014.

As an incoming freshman, Bringewatt was eager to dive into theoretical physics research. During the first couple weeks of classes, he sought out Cohen to ask about joining a theoretical research project.

“He told me that I shouldn't do theory, even though he's a theorist,” Bringewatt said. “One should only do theory if they're like really bad at experiments or can't imagine doing anything else. I’ve learned since this is his standard line for eager undergrads.”

Bringewatt took Cohen’s advice and sought out an experimentalist: Physics Professor Carter Hall. Bringewatt joined Hall’s team and initially crunched numbers—analyzing experimental data instead of getting his hands dirty with experimental equipment. He eventually handled equipment in the lab and quickly realized it wasn’t for him. He still felt drawn to the math and theory side of physics. So he returned to Cohen, who directed him to Physics Professor William Dorland who was on sabbatical at the time.

The summer before his junior year, Bringewatt wrote some computer code for Dorland to use in an ongoing project investigating how plasmas move. Dorland, who is a computational physicist, was interested in quantum computing and decided to spend some of his time during his sabbatical exploring the basics of quantum computation with Bringewatt. Their discussions developed into a collaboration with Stephen Jordan, who was then an adjunct associate professor of physics at UMD. The group investigated adiabatic quantum computation—a version of quantum computing that involves gradually evolving one quantum state into another. Bringewatt was the first author of a paper the collaboration wrote comparing the adiabatic quantum computing approach to a classical alternative. The experience focused Bringewatt on theoretical physics.

“I haven't really looked back since then,” Bringewatt said. “Maryland is a really good place to be for quantum computing. And, as a highly interdisciplinary field, it really does bring out the things I like most about research.”

Having settled on studying quantum theory, Bringewatt still had to decide where to attend grad school. UMD’s many experts and diverse research opportunities once again moved it to the top of his list. But he wanted to experience working in another group. So, before he graduated in 2018, he started visiting with professors. He found a match that felt right with Alexey Gorshkov, an adjunct associate professor of physics at UMD, and his group, which works on a broad range of theoretical physics topics.

During graduate school, Bringewatt has continued investigating adiabatic quantum computation, including collaborating with Michael Jarret (Ph.D. ’16, physics), who is now an assistant professor in the Mathematical Sciences Department at George Mason University. Together, they wrote a paper comparing classical and quantum adiabatic techniques for simulating quantum physics.

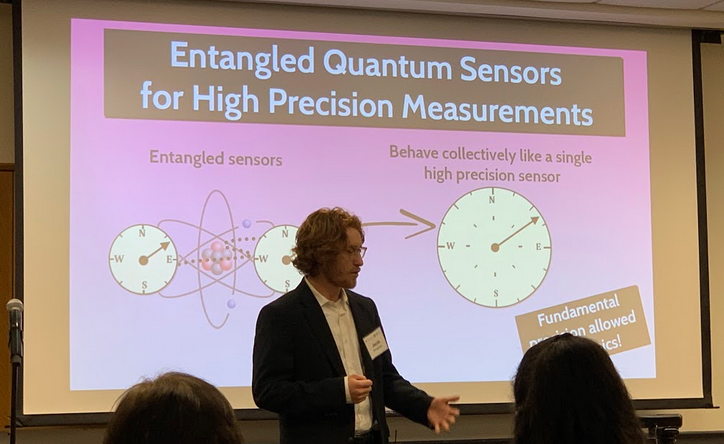

Bringewatt also took on other challenges. A significant portion of his graduate research focuses on using quantum physics to push the limits of measurement technologies. This research involves improving sensor precision by optimizing the use of quantum entanglement—a fundamental quantum phenomenon that connects quantum particles and allows them to ignore some constraints of classical physics. The work looks at the smallest parts that contribute to a sensor, how the pieces interact, and how they come together during a measurement. By understanding sensors at this fundamental level, future technologies might be able to operate at the limits of what is allowed by physics.

Bringewatt shared this part of his research during the 2022 Three-Minute Thesis (3MT) competition hosted by UMD. 3MT competitions are hosted by many universities around the world to encourage graduate students to practice communicating technical research clearly and succinctly. In these events, the competitors distill a research project into a three-minute presentation that is accessible to someone unfamiliar with their field. Bringewatt was one of the eight winners in the campuswide competition, earning him a $1,000 prize.

Jacob Bringewatt delivers his 3-minute thesis.“It was a fun challenge to explain in three minutes the big ideas behind a line of research I've been pursuing for several years with a number of excellent collaborators in Alexey Gorshkov's group,” Bringewatt said.

Jacob Bringewatt delivers his 3-minute thesis.“It was a fun challenge to explain in three minutes the big ideas behind a line of research I've been pursuing for several years with a number of excellent collaborators in Alexey Gorshkov's group,” Bringewatt said.

As part of one of his projects on quantum sensor networks, Bringewatt, Gorshkov and UMD physics graduate student Adam Ehrenberg investigated the peak performance that networks of quantum sensors can achieve. His project built on previous work that had already established the best performance that is physically possible. Crucially, those results had assumed the maximum amount of entanglement—all the sensors are always connected to all the other sensors. But practically achieving maximum entanglement is difficult work, so Bringewatt and colleagues flipped the problem on its head. They identified the minimum amount of entanglement needed to achieve an optimal measurement, which for some cases didn't require maximum entanglement. They then developed protocols that achieve the theoretical target they had set. The team’s efforts earned them a place among the 12 groups of finalists for the 2022 UMD Invention of the Year Award.

"I'm honored to have gotten a chance to collaborate with Jake on many projects,” Gorshkov said. “I learned a lot from him and am very proud of his numerous achievements and well-deserved awards."

Even while juggling classes and research into both quantum sensors and adiabatic quantum computing, Bringewatt sought out new challenges. For his first four years as a graduate student, he was a Department of Energy (DOE) Computational Science Graduate Fellow. The program requires fellows to spend a summer working at a DOE laboratory, and it encourages them to explore new topics.

Bringewatt was eager to try something completely new. He knew Zohreh Davoudi, associate professor of physics at UMD, from his undergraduate math methods course. And he was aware she studied nuclear theory and was interested in branching into quantum simulations. He thought a summer of nuclear theory might be interesting and have the additional benefit of providing a foundation to work with Davoudi. So, the first summer after starting graduate school, he requested to spend his summer at Jefferson Lab, which is home to a particle accelerator used for nuclear physics experiments.

He spent his summer there as part of a team investigating the internal structure of protons. This small sample of nuclear physics research left Bringewatt eager for more, so he reached out to Davoudi. The timing worked out: She was looking for colleagues to collaborate with on developing quantum simulations of nuclear physics.

He began attending Davoudi’s group meetings, and they eventually began pooling their skills on a project. Earlier this year, they published a paper on finding the best way to represent fermions—particles like electrons that can’t share their quantum state—and their interactions within quantum computer simulations.

The topics of nuclear theory, quantum sensor research and adiabatic quantum computing have given Bringewatt diverse challenges and experiences throughout graduate school. As a result of his prodigious work ethic, he has been first author on ten research papers—an unusually high count for a graduate student.

“Being able to pursue these three distinct topics has been a real advantage of being here where there's a lot of experts on a wide array of things,” Bringewatt said. “I've gotten the chance to work with a lot of talented people with different areas of expertise, which has been really nice.”

Earlier this year, the College of Computer, Mathematical and Natural Sciences acknowledged his hard work and gave him the 2023 Board of Visitors Outstanding Graduate Student Award and a $5,000 prize.

“I feel very honored to have received this recognition,” Bringewatt said. “Scientific research is never an individual effort, and having pursued both my undergraduate and graduate degree at the University of Maryland, I am extremely grateful to the university and all my mentors here who have enabled me to grow and excel as a young scientist.”

Bringewatt is wrapping up his research at UMD and looking for new collaborations and challenges as a postdoctoral researcher. He plans to graduate in the spring of 2024.

“I've been very happy to be at UMD,” Bringewatt said. “It's a great community, and, I think, the best of both worlds: It has a bunch of resources and world-class research, but people are also very approachable, friendly, and helpful. I feel extremely lucky for the years I’ve gotten to spend here.”

Written by Bailey Bedford

Related news stories:https://umdphysics.umd.edu/about-us/news/department-news/1639-davoudi-f20.html

https://umdphysics.umd.edu/events/aboutus-outreach/maryland-day/66-academics/student-services/761-student-spotlight-joshua-parker.html