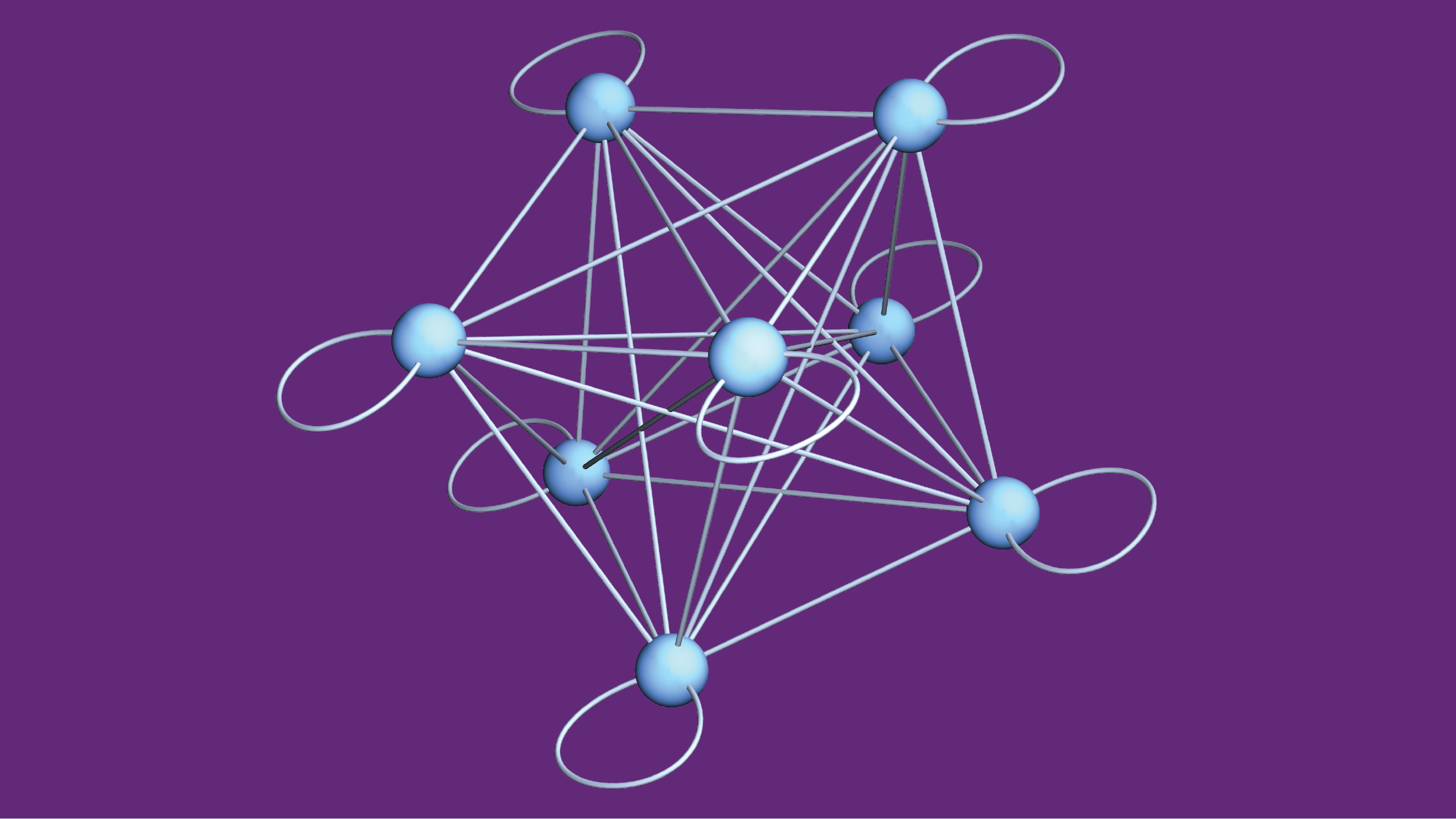

Quantum particles have unique properties that make them powerful tools, but those very same properties can be the bane of researchers. Each quantum particle can inhabit a combination of multiple possibilities, called a quantum superposition, and together they can form intricate webs of connection through quantum entanglement.

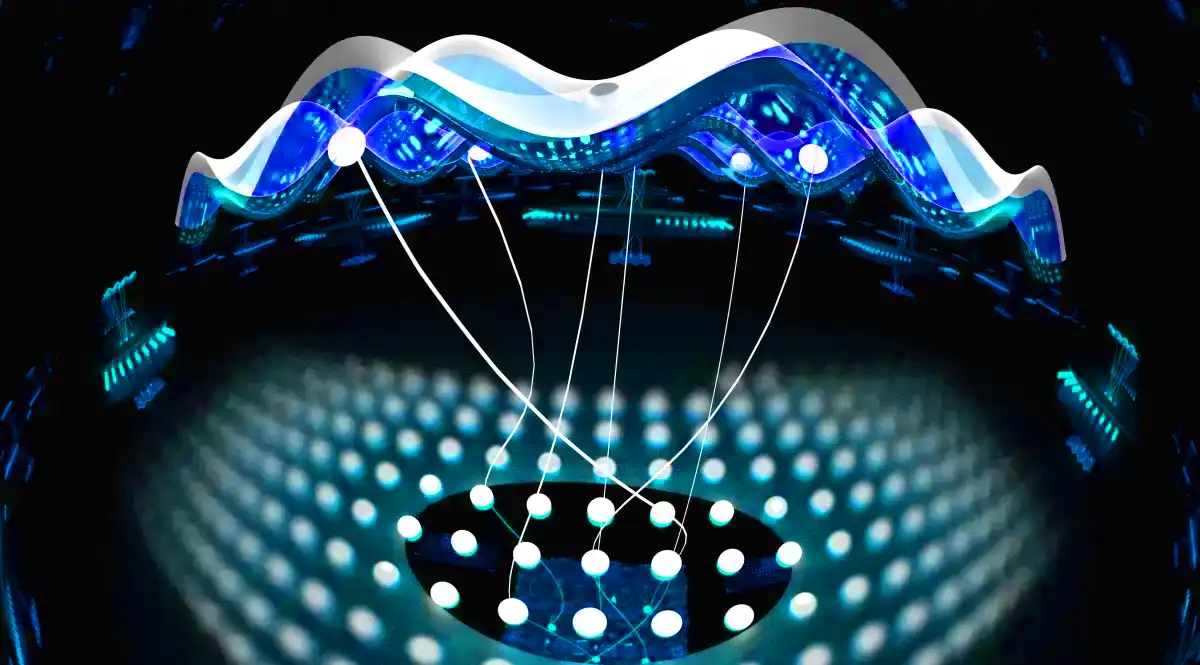

These phenomena are the main ingredients of quantum computers, but they also often make it almost impossible to use traditional tools to track a collection of strongly interacting quantum particles for very long. Both human brains and supercomputers, which each operate using non-quantum building blocks, are easily overwhelmed by the rapid proliferation of the resulting interwoven quantum possibilities.  A spring-like force, called the strong force, works to keep quarks—represented by glowing spheres—together as they move apart after a collision. Quantum simulations proposed to run on superconducting circuits might provide insight into the strong force and how collisions produce new particles. The diagrams in the background represent components used in superconducting quantum devices. (Credit: Ron Belyansky)

A spring-like force, called the strong force, works to keep quarks—represented by glowing spheres—together as they move apart after a collision. Quantum simulations proposed to run on superconducting circuits might provide insight into the strong force and how collisions produce new particles. The diagrams in the background represent components used in superconducting quantum devices. (Credit: Ron Belyansky)

In nuclear and particle physics, as well as many other areas, the challenges involved in determining the fate of quantum interactions and following the trajectories of particles often hinder research or force scientists to rely heavily on approximations. To counter this, researchers are actively inventing techniques and developing novel computers and simulations that promise to harness the properties of quantum particles in order to provide a clearer window into the quantum world.

Zohreh Davoudi, an associate professor of physics at the University of Maryland and Maryland Center for Fundamental Physics, is working to ensure that the relevant problems in her fields of nuclear and particle physics don’t get overlooked and are instead poised to reap the benefits when quantum simulations mature. To pursue that goal, Davoudi and members of her group are combining their insights into nuclear and particle physics with the expertise of colleagues—like Adjunct Professor Alexey Gorshkov and Ron Belyansky, a former JQI graduate student under Gorshkov and a current postdoctoral associate at the University of Chicago—who are familiar with the theories that quantum technologies are built upon.

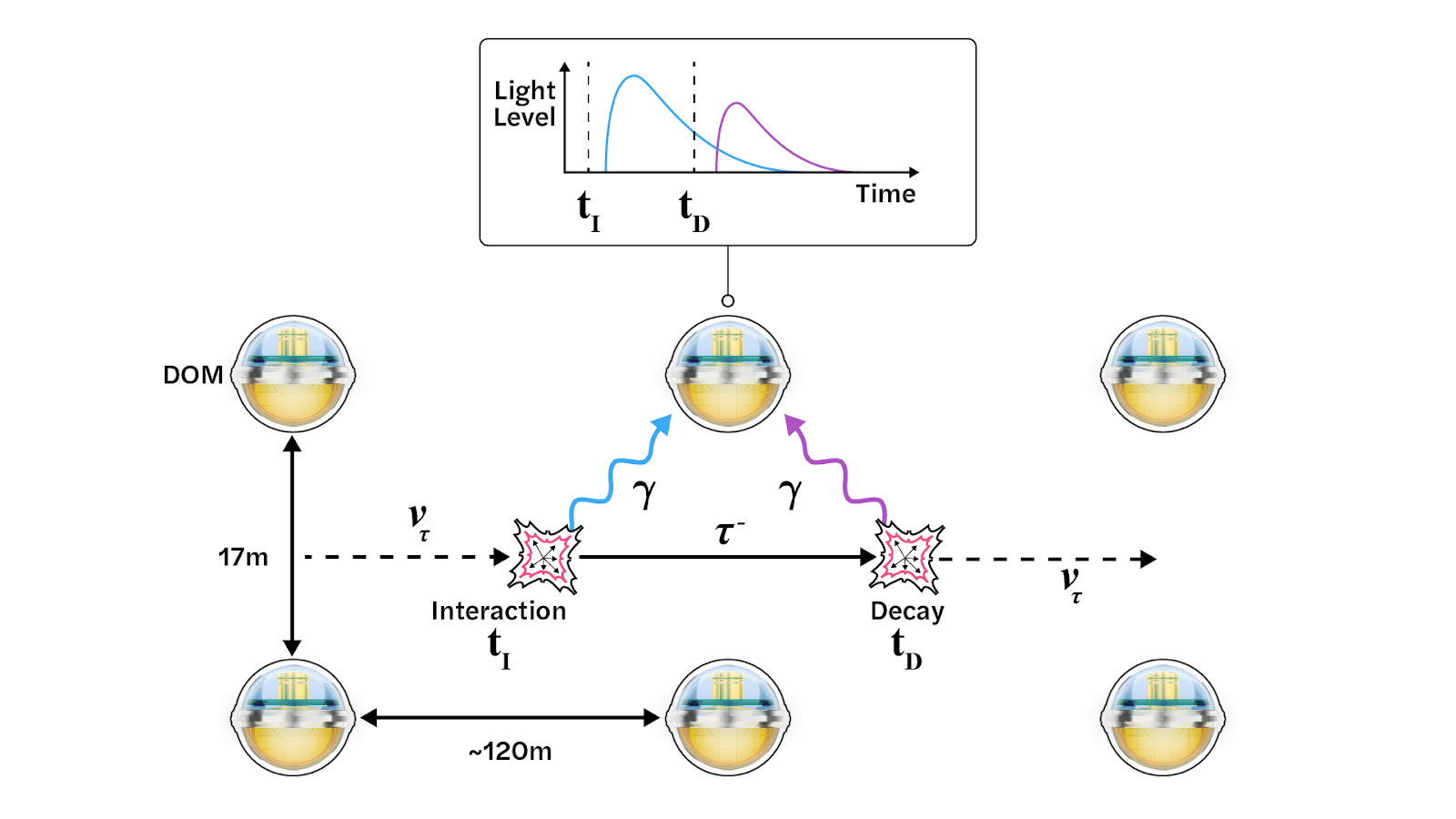

In an article published earlier this year in the journal Physical Review Letters, Belyansky, who is the first author of the paper, together with Davoudi, Gorshkov and their colleagues, proposed a quantum simulation that might be possible to implement soon. They propose using superconducting circuits to simulate a simplified model of collisions between fundamental particles called quarks and mesons (which are themselves made of quarks and antiquarks). In the paper, the group presented the simulation method and discussed what insights the simulations might provide about the creation of particles during energetic collisions.

Particle collisions—like those at the Large Hadron Collider—break particles into their constituent pieces and release energy that can form new particles. These energetic experiments that spawn new particles are essential to uncovering the basic building blocks of our universe and understanding how they fit together to form everything that exists. When researchers interpret the messy aftermath of collision experiments, they generally rely on simulations to figure out how the experimental data matches the various theories developed by particle physicists.

Quantum simulations are still in their infancy. The team’s proposal is an initial effort that simplifies things by avoiding the complexity of three-dimensional reality, and it represents an early step on the long journey toward quantum simulations that can tackle the most realistic fundamental theories that Davoudi and other particle physicists are most eager to explore. The diverse insights of many theorists and experimentalists must come together and build on each other before quantum simulations will be mature enough to tackle challenging problems, like following the evolution of matter after highly energetic collisions.

“We, as theorists, try to come up with ideas and proposals that not only are interesting from the perspective of applications but also from the perspective of giving experimentalists the motivation to go to the next level and push to add more capabilities to the hardware,” says Davoudi, who is also a Fellow of the Joint Center for Quantum Information and Computer Science (QuICS) and a Senior Investigator at the Institute for Robust Quantum Simulation (RQS).“There was a lot of back and forth regarding which model and which platform. We learned a lot in the process; we explored many different routes.”

A Quantum Solution to a Quantum Problem

The meetings with Davoudi and her group brought particle physics concepts to Belyansky’s attention. Those ideas were bouncing around inside his head when he came across a mathematical tool that allows physicists to translate a model into a language where particle behaviors look fundamentally different. The ideas collided and crystallized into a possible method to efficiently simulate a simple particle physics model, called the Schwinger model. The key was getting the model into a form that could be efficiently represented on a particular quantum device.

Belyansky had stumbled upon a tool for mapping between certain theories that describe fermions and theories that describe bosons. Every fundamental quantum particle is either a fermion or boson, and whether a particle is one or the other governs how it behaves. If a particle is a fermion, like protons, quarks and electrons, then no two of that type of particle can ever share the same quantum state. In contrast, bosons, like the mesons formed by quarks, are willing to share the same state with any number of their identical brethren. Switching between two descriptions of a theory can provide researchers with entirely new tools for tackling a problem.

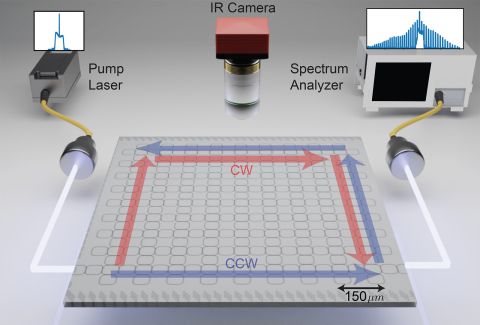

Based on Belyansky’s insight, the group determined that translating the fermion-based description of the Schwinger model into the language of bosons could be useful for simulating quark and meson collisions. The translation put the model into a form that more naturally mapped onto the technology of circuit quantum electrodynamics (QED). Circuit QED uses light trapped in superconducting circuits to create artificial atoms, which can be used as the building blocks of quantum computers and quantum simulations. The pieces of a circuit can combine to behave like a boson, and the group mapped the boson behavior onto the behavior of quarks and mesons during collisions.

This type of simulation that uses a device’s natural behaviors to directly mimic a behavior of interest is called an analog simulation. This approach is generally more efficient than designing simulations to be compatible with diverse quantum computers. And since analog approaches lean into the underlying technology’s natural behavior, they can play to the strengths of early quantum devices. In the paper, the team described how their analog simulation could run on a relatively simple quantum device without relying on many approximations.

"It is particularly exciting to contribute to the development of analog quantum simulators—like the one we propose—since they are likely to be among the first truly useful applications of quantum computers," says Gorshkov, who is also a Physicist at the National Institute of Standards and Technology, a QuICS Fellow and an RQS Senior Investigator.

The translation technique Belyansky and his collaborators used has a limitation: It only works in one space dimension. The restriction to one dimension means that the model is unable to replicate real experiments, but it also makes things much simpler and provides a more practical goal for early quantum simulations. Physicists call this sort of simplified case a toy model. The team decided this one-dimensional model was worth studying because its description of the force that binds quarks into mesons—the strong force—still shares features with how it behaves in three space dimensions.

“Playing around with these toy models and being able to actually see the outcome of these quantum mechanical collision processes would give us some insight as to what might go on in actual strong force processes and may lead to a prediction for experiments,” Davoudi says. “That's sort of the beauty of it.”

Scouting Ahead with Current Computers

The researchers did more than lay out a proposal for experimentally implementing their simulations using quantum technology. By focusing on the model under restrictions, like limiting the collision energy, they simplified the calculations enough to explore certain scenarios using a regular computer without any quantum advantages.

Even with the imposed limitations, the simplified model was still able to simulate more than the most basic collisions. Some of the simulations describe collisions that spawned new particles instead of merely featuring the initial quarks and mesons bouncing around without anything new popping up. The creation of particles during collisions is an important feature that prior simulation methods fell short of capturing.

These results help illustrate the potential of the approach to provide insights into how particle collisions produce new particles. While similar simulation techniques that don’t harness quantum power will always be limited, they will remain useful for future quantum research: Researchers can use them in identifying which quantum simulations have the most potential and in confirming if a quantum simulation is performing as expected.

Continuing the Journey

There is still a lot of work to be done before Davoudi and her collaborators can achieve their goal of simulating more realistic models in nuclear and particle physics. Belyansky says that both one-dimensional toy models and the tools they used in this project will likely deliver more results moving forward.

“To get to the ultimate goal, we need to add more ingredients,” Belyansky says. “Adding more dimensions is difficult, but even in one dimension, we can make things more complicated. And on the experimental side, people need to build these things.”

For her part, Davoudi is continuing to collaborate with several research groups to develop quantum simulations for nuclear and particle physics research.

“I'm excited to continue this kind of multidisciplinary collaboration, where I learn about these simpler, more experimentally feasible models that have features in common with theories of interest in my field and to try to see whether we can achieve the goal of realizing them in quantum simulators,” Davoudi says. “I'm hoping that this continues, that we don't stop here.”

Original story by Bailey Bedford: https://jqi.umd.edu/news/particle-physics-and-quantum-simulation-collide-new-proposal