Going Beyond the Anti-Laser May Enable Long-Range Wireless Power Transfer

- Details

- Published: Tuesday, November 17 2020 05:00

Ever since Nikola Tesla spewed electricity out in all directions with his coil back in 1891, scientists have been thinking up ways to send electrical power through the air. The dream is to charge your phone or laptop, or maybe even a healthcare device such as a pacemaker, without the need for wires and plugs. The tricky bit is getting the electricity to find its intended target, and getting that target to absorb the electricity instead of just reflect it back into the air—all preferably without endangering anyone along the way.

These days, you can wirelessly charge a smartphone by putting it within an inch of a charging station. But usable long-range wireless power transfer, from one side of a room to another or even across a building, is still a work in progress. Most of the methods currently in development involve focusing narrow beams of energy and aiming them at their intended target. These methods have had some success, but are so far not very efficient. And having focused electromagnetic beams flying around through the air is unsettling. Arcs of electricity generated by a Tesla coil. (Credit: Airarcs/CC BY-SA 3.0)

Arcs of electricity generated by a Tesla coil. (Credit: Airarcs/CC BY-SA 3.0)

Now, a team of researchers at the University of Maryland (UMD), in collaboration with a colleague at Wesleyan University in Connecticut, have developed an improved technique for wireless power transfer technology that may promise long-range power transmission without narrowly focused and directed energy beams. Their results, which widen the applicability of previous techniques, were published Nov. 17, 2020 in the journal Nature Communications.

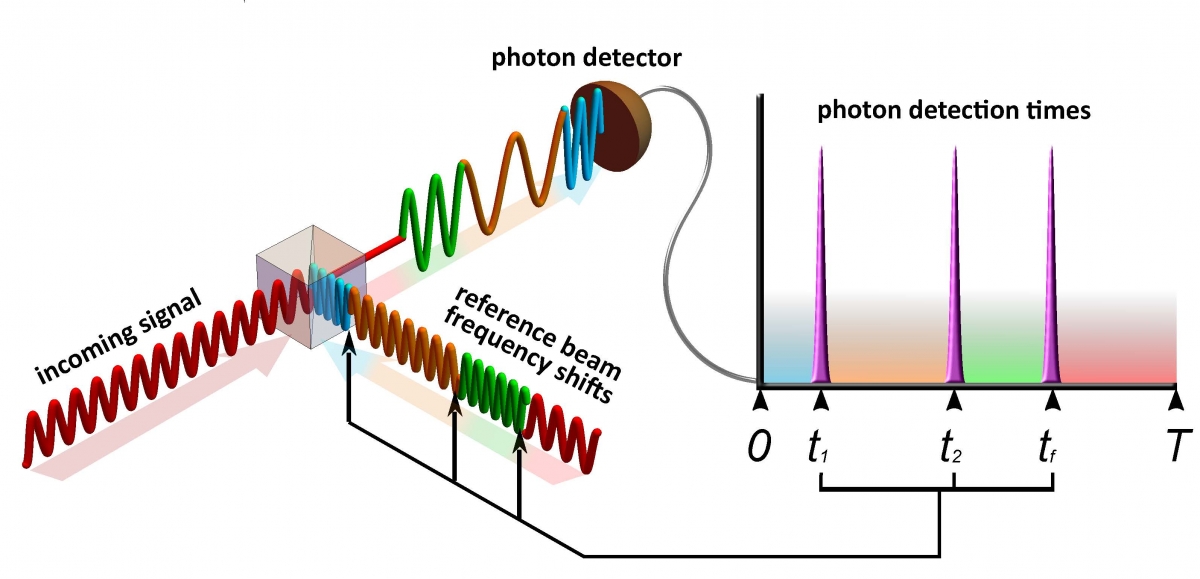

The team generalized a concept known as an “anti-laser.” In a laser, one photon triggers a cascade of many photons of the same color shooting out in a coherent beam. In an anti-laser, the reverse happens. Instead of boosting the number of photons, an anti-laser coherently and perfectly absorbs a beam of many precisely tuned photons. It’s kind of like a laser running backwards in time.

The new work, led by UMD Professor of Physics Steven Anlage of the Quantum Materials Center (QMC), demonstrates that it’s possible to design a coherent perfect absorber outside of the original time-reversed laser framework—a relaxation of some of the key constraints in earlier work. Instead of assuming directed beams traveling along straight lines into an absorption target, they picked a geometry that was disorderly and not amenable to being run backwards in time.

“We wanted to see this effect in a completely general environment where there's no constraints,” says Anlage. “We wanted a sort of random, arbitrary, complex environment, and we wanted to make perfect absorption happen under those really demanding circumstances. That was the motivation for this, and we did it.”

Anlage and his colleagues wanted to create a device that could receive energy from a more diffuse source, something that was less beam and more bath. Before tackling the wireless challenge, they set up their generalized anti-laser as a labyrinth of wires for electromagnetic waves to travel through. Specifically, they used microwaves, a common candidate for power transfer applications. The labyrinth consisted of a bunch of wires and boxes connected in a purposefully disordered way. Microwaves going through this labyrinth would get so tangled up that, even if it were possible to reverse time, this still wouldn’t untangle them.

Buried in the midst of this labyrinth was an absorber, the target to deliver power to. The team sent microwaves of different frequencies, amplitudes and phases into the labyrinth and measured how they were transformed. Based on these measurements, they were able to calculate the exact properties of input microwaves that would result in perfect power transfer to the absorber. They found that for correctly chosen input microwaves, the labyrinth absorbed an unprecedented 99.999% of the power they sent into it. This showed explicitly that coherent perfect absorption can be achieved even without a laser run backwards in time.

The team then took a step towards wireless power transfer. They repeated the experiment in a cavity, a plate of brass several feet in each direction with an oddly shaped hole in the middle. The shape of the hole was designed so that the microwaves would bounce around it in an unpredictable, chaotic way. They placed a power absorber inside the cavity, and sent microwaves in to bounce around the open space inside. They were able to find the right input microwave conditions for coherent perfect absorption with 99.996% efficiency.

Recent work by a collaboration of teams in France and Austria also demonstrated coherent perfect absorption in their own disordered microwave labyrinth. However, their experiment was not quite as general as the new work from Anlage and colleagues. In the previous work, the microwaves entering the labyrinth would still be untangled by a hypothetical reversal of time. This might seem like a subtle distinction, but the authors say showing that coherent perfect absorption doesn’t require any kind of order in the environment promises applicability virtually anywhere.

Generalizing previous techniques in this way invites ideas that sound like science fiction, like being able to wirelessly and remotely charge any object in a complex environment, such as an office building, with near perfect efficiency. Such schemes would require that the frequency, amplitude, and phase of the electric power is custom tuned to specific targets. But there would be no need to focus a high-powered beam and aim it at the laptop or phone—the electrical waves themselves would be designed to find their chosen target.

“If we have an object which we want to deliver power to, we will first use our equipment to measure some properties of the system,” says Lei Chen, a graduate student in electrical and computer engineering at UMD and the lead author of the paper. “Based on those properties we can get the unique microwave signals for this kind of system. And it will be perfectly absorbed by the object. For every unique object, the signals will be different and specially designed.”

Although this technique shows great promise, much remains to be done before the advent of wireless and plug-less offices. The perfect absorber depends crucially on the power being tuned just right for the absorber. A slight change in the environment—such as moving the target laptop or raising the blinds in the room—would require an immediate retuning of all the parameters. So, there would need to be a way to quickly and efficiently find the right conditions for perfect absorption on the fly, without using too much power or bandwidth. Additionally, more work needs to be done to determine the efficacy and safety of this technique in realistic environments.

Even though it’s not yet time to throw away all your power cords, coherent perfect absorption may come in handy in many ways. Not only is it general to any kind of target, it is also not limited to optics or microwaves. “It's not wedded to one specific technology,” says Anlage, “This is a very general wave phenomenon. And the fact that it's done in microwaves is just because that's where the strengths are in my lab. But you could do all of this with acoustics, you could do this with matter waves, you could do this with cold atoms. You could do this in many, many different contexts.”

In addition to Chen and Anlage, Tsampikos Kottos, a professor at Wesleyan University, was a co-author on the paper.

Written by Dina Genkina (This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.)