Taking the SMART Path

- Details

- Category: Department News

- Published: Thursday, January 26 2023 00:01

In 2021, when Isabelle Brooks left her home in Minnesota to study physics at the University of Maryland, she knew it would mean a big transition—from an all-girls high school with fewer than 500 students to a huge college campus with more than 40,000 students. It turned out to be even more exciting than she expected.

“It was definitely a culture shock,” Brooks recalled. “I told my roommate it was crazy to me that I kept seeing so many faces I didn’t recognize. I was around so many different people doing so many differ Isabelle Brooksent things—it was a really cool and exciting experience.”

Isabelle Brooksent things—it was a really cool and exciting experience.”

Brooks’ experiences have exceeded her expectations in more ways than one, and although she’s only a sophomore she’s already charting her path toward a career in physics. One big boost in that direction came last year when she was awarded a Department of Defense SMART (Science, Mathematics, and Research for Transformation) Scholarship.

SMART Scholars receive full tuition for up to five years and hands-on internship experience working directly with an experienced mentor at one of over 200 innovative laboratories across the Army, Navy, Air Force and Department of Defense, plus a stipend and full-time employment with the Department of Defense after graduation.

This summer, Brooks will intern at a U.S. Army facility in Maryland.

“I’ll be working at Aberdeen Proving Ground with the Department of Defense,” Brooks said. “The lab I’ll be working with focuses on satellite communications and other innovative technologies for our armed forces. It’s super exciting.”

Physics in the family

Always a strong student, Brooks got an early introduction to physics thanks to her father who studied physics when he was in college.

“My dad was my biggest influence,” she explained. “He’s a patent attorney now and he works with a lot of science and technology, which has been super cool to watch as I’ve been growing up.”

Despite her interest in her dad’s work, Brooks wasn’t initially drawn to physics herself.

“My dad was always like, ‘It’s really important to study science,’ but I didn’t really want to,” Brooks recalled. “My freshman year in high school I actually did not do well in my introductory physics class at all, I didn’t like the content and I told my dad, ‘I’m never doing this.’”

All it took was one class to change her mind.

“In my senior year I ended up taking honors physics and I had the best, most supportive most influential professor who helped me understand that I am really good at this and there is an opportunity for me to do much more with it,” she said. “After that, it really made sense to me—I liked seeing how physics is playing out in the real world, and I knew this was something I wanted to do.”

So many possibilities

In the summer after Brooks’ first year at UMD, one of her relatives who works with the Defense Department encouraged her to apply for the SMART Scholarship to help her achieve her dream of a degree in physics. Months later she got the news she was hoping for.

“I was checking my inbox every day and when I saw the email I was shaking because I knew this had to be it,” she recalled. “When I opened the email and got the good news that I’d received the scholarship I just felt so honored. There are just so many possibilities that can come from this.”

Since then, regular check-in meetings with her SMART mentor James Mink, Chief of the Tactical Systems Branch (SATCOM) have helped Brooks learn more about the opportunities ahead and prepare for her summer internships. This summer—and every summer until she graduates—she’ll work directly with her mentor at the U.S. Army DEVCOM C5ISR Center - Aberdeen Proving Ground, gaining valuable hands-on experience and training that will prepare her for a full-time position there after graduation.

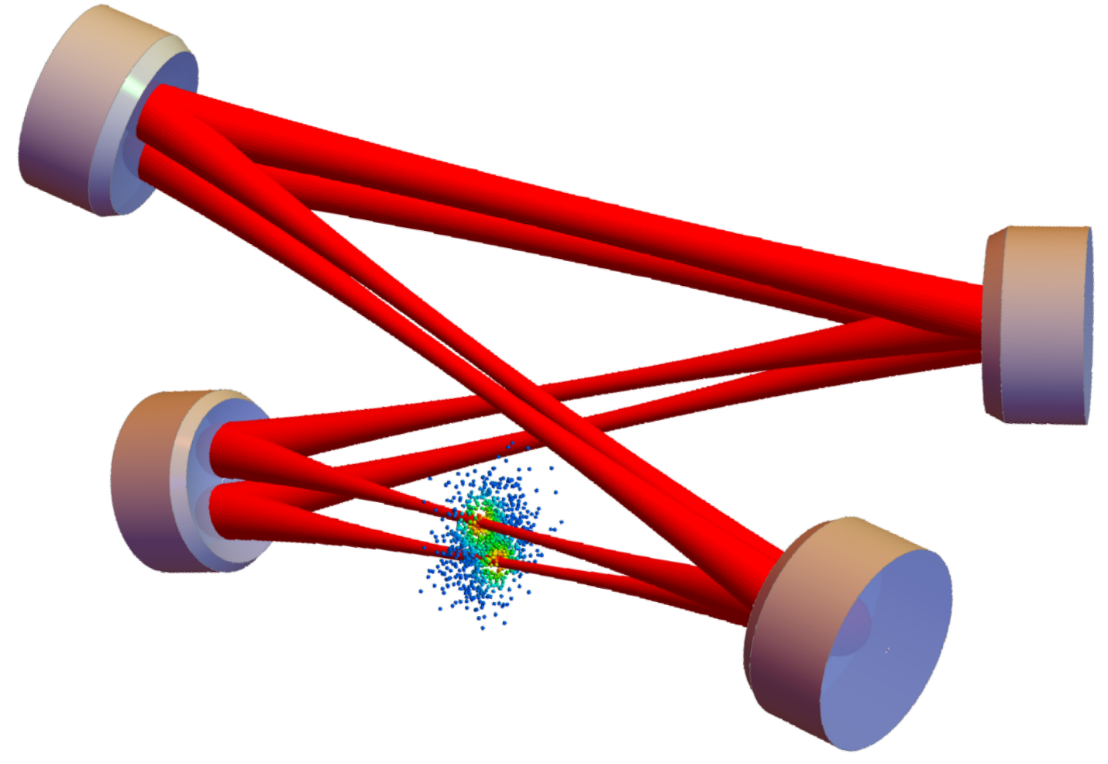

Brooks credits her participation in the FIRE (First-Year Innovation and Research Experience) program and her work with the Simulating Particle Detection research group for helping her build a strong foundation for her research, which has also focused on the challenges of quantum Fourier transforms—mathematical models that help to transform the signals between two different domains.

She’s gained more confidence in herself and her abilities every step of the way.

“My parents always raised me to believe I could do anything I put my mind to, overcome any obstacle, but I think coming to such a big school, at first I wasn’t sure if I could really do this,” she recalled. “But now I just feel like I’ve opened up so much more confidence in myself and an awareness of my ability and my strength as a student, and that feels really good.”

Brooks continues to explore her fascination with physics in exciting and unexpected ways, thanks to professors who challenge and inspire her. Her favorite class this year was PHYS 235: The Making of the Atomic Bomb.

“It’s taught by Professor Sylvester Gates, who I think is the coolest person ever,” Brooks said. “I was so excited when I was in that class, but it was definitely hard. If I wasn’t a physics major, I think I’d be crying with the problem sets we had and the material we worked on, but that class and a lot of my physics classes have pushed me to think in new ways.”

It's been less than two years since Brooks came to UMD from a small Minnesota high school, but now as she pursues her passion for physics and looks ahead to the opportunities that will come with her SMART Scholarship, she’s thinking big.

“I just have this feeling that I can do a lot more with my life and my education than I ever grasped,” she explained. “I think with this Defense Department scholarship I’ll most likely pivot towards applied research and satellite communication technology, and knowing that the work I’ll be doing will actually support people who fight for our country is incredibly amazing. I can’t wait to make a difference.”

Written by Leslie Miller