Frank Zhao Cooks Up New Materials to Create Unique Quantum Behaviors

- Details

- Published: Friday, February 06 2026 01:40

When Frank Zhao was about four years old and growing up in China, his parents sent him to a children’s astronomy program. It introduced him first to mythological stories associated with the heavens and eventually exposed him to the explanation of how the solar system formed and the histories of distant stars. Those early astronomy lessons ensnared his attention and introduced him to the way physics can reveal hidden stories about the world. But what started as an interest in the stars led him on a winding path to a career building new quantum materials with unique properties.

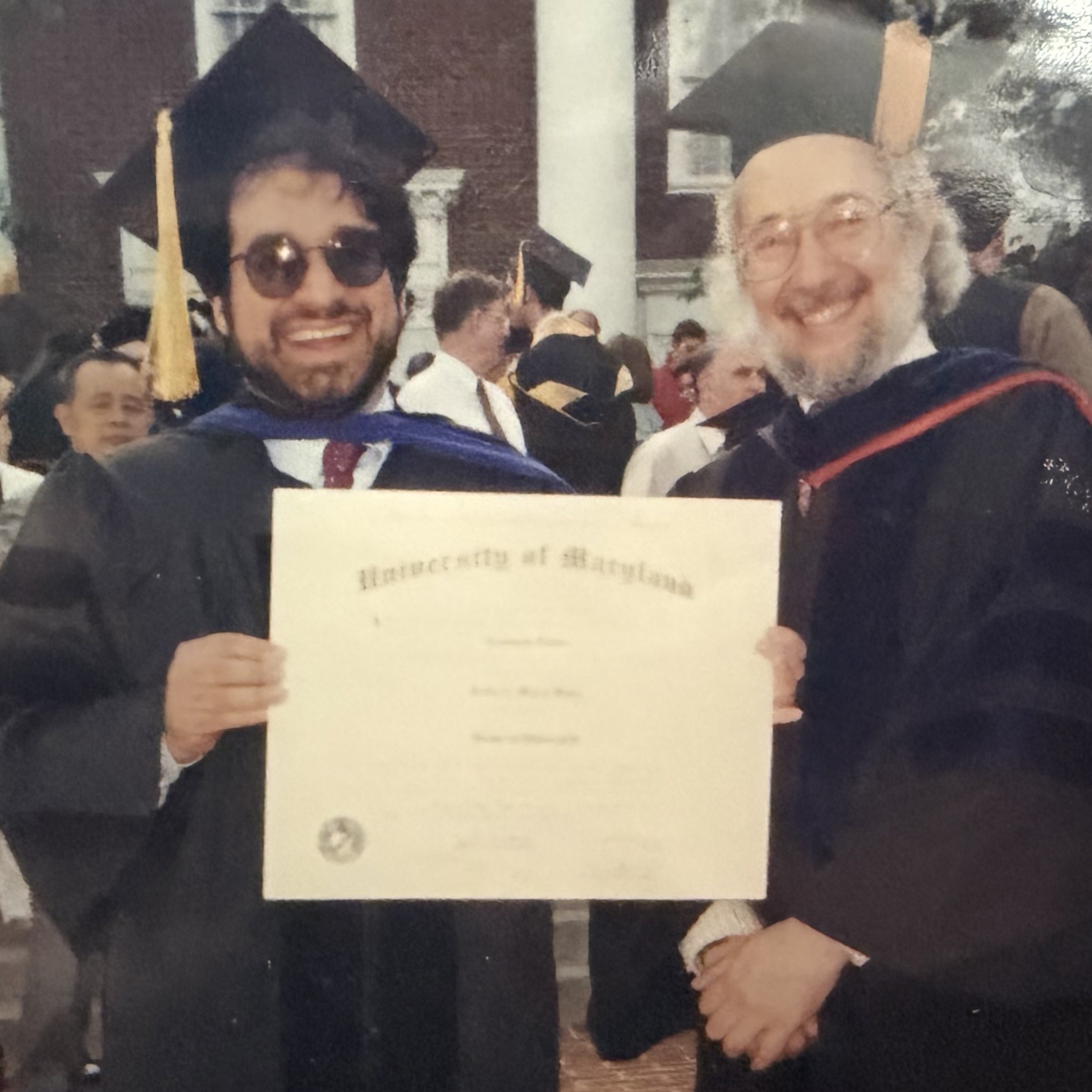

He carried his love of astronomy through high school, and when he went to the University of Toronto as an undergraduate, he originally planned to study astrophysics. During his second year there, he joined a condensed matter physics lab for a research class, and the experience changed his plans. The challenges of unraveling what happens in materials and the excitement of hands-on experiments captivated him. Frank Zhao

Frank Zhao

Zhao went on to create and study new materials as a graduate student at Columbia University and Harvard University and then as a postdoctoral associate at MIT. Now, he is setting up his own lab as an assistant professor of physics at the University of Maryland and a member of the Quantum Materials Center.

At UMD, Zhao plans for his research to build on the experiments he performed as a graduate student and postdoctoral researcher. He plans to fabricate new materials, study their properties and investigate how they might be incorporated into new technologies. In particular, he is interested in materials with thin layers that are loosely connected instead of being tied tightly together the same way the atoms are within each layer. He is especially interested in the interfaces of the layers in the materials. Such loosely connected layers exist in a variety of crystals, and they allow researchers to repeatedly peel off layers until they are left with a single layer.

“What this allows you to do is stack these materials up like a deck of cards,” Zhao says. “And just like a deck of cards, you can mix and match different cards from different decks to make artificial crystals that you can't make naturally.”

Making these stacks is an opportunity to create a wide range of samples with unique properties. The variety of possible properties makes the samples useful for research, but often the thin layers of materials can be challenging to work with. Single layers of materials can be heavily influenced by small imperfections and sometimes merely exposing them to the air can cause rapid contamination that destroys the quantum features that Zhao and other researchers want to study.

Zhao started stacking films when he went to Columbia University for graduate school in 2012 and joined Philip Kim’s lab. There he learned about Bi2Sr2CaCu2O8+x (BSCCO), which seemed like it might be an interesting material for studying superconductivity. Researchers already knew that BSCCO was made up of thin sheets that could each carry a superconducting current, meaning that under the right conditions electrons in the sheets could pair up and flow without any resistance. Theorists had predicted that tweaking the orientation between layers of BSCCO by twisting them relative to one another could change the behavior of superconducting currents flowing between the layers, confirming details about how superconductivity works in the material. In theory, a simple twist of adjacent layers should change how large a superconducting current the sample could host, and the current should almost disappear for a 45-degree offset.

Kim’s group could peel apart BSCCO and other crystals—a process called exfoliation—and they could also restack them at a particular angle. However, Kim knew that wasn’t enough to confirm the predictions. For more than a decade, multiple experiments had done the same with BSCCO and failed to definitively observe the expected dependence of the currents for different angles. But the prior experiments all appeared to have messy interfaces that likely altered their behavior. Zhao took on the challenge of developing a recipe for creating BSCCO samples with pristine surfaces and acquiring the tools necessary to cook them up.

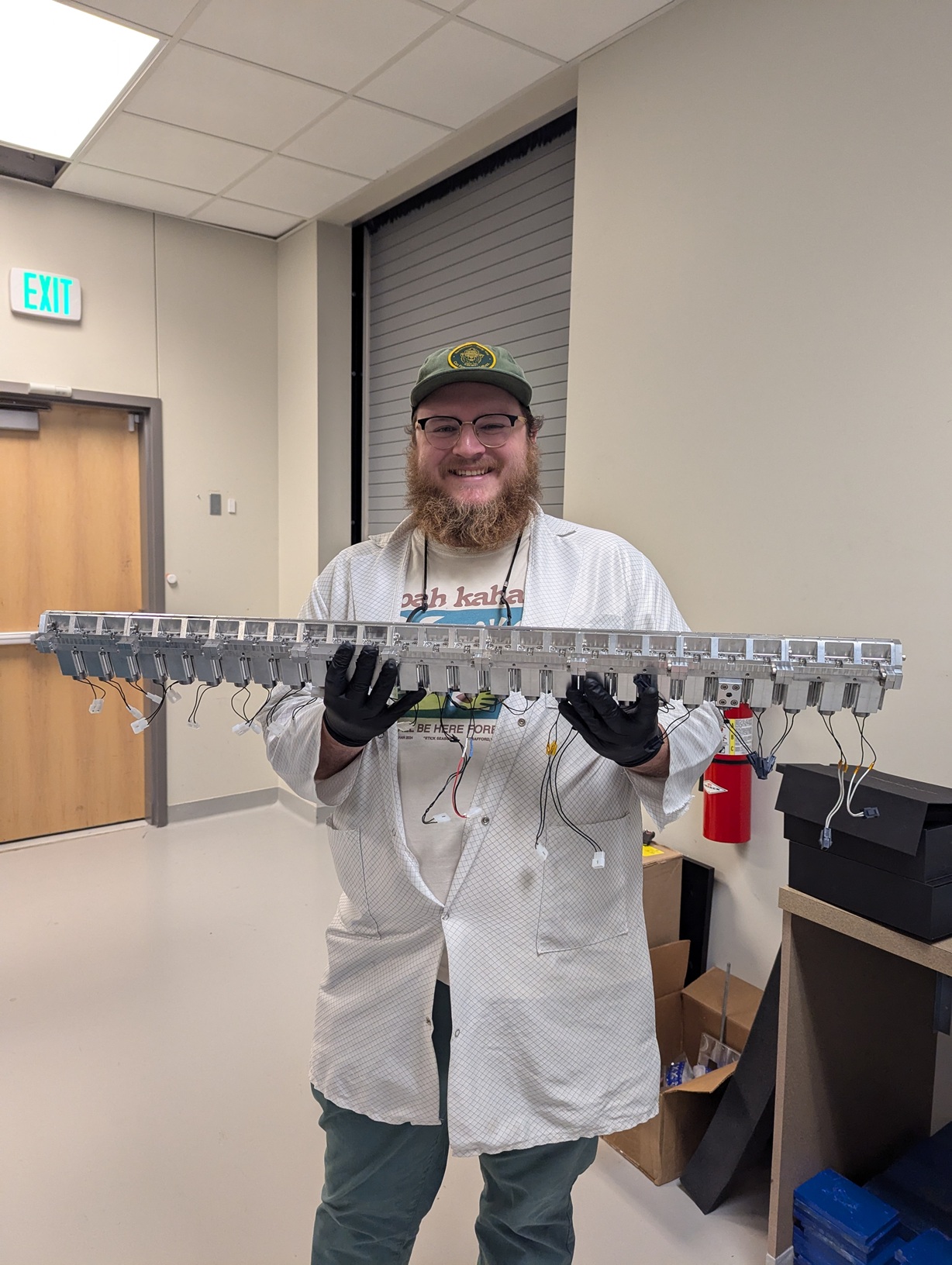

“I think of myself as a recipes guy,” Zhao says. “The thing I really liked about this work is that we built the machine from zero—at the time my advisor moved from Columbia to Harvard. So we had to really go from having an empty lab to buying the equipment, talking to the companies and trying to figure out what we needed, and then we put it together. But we had no idea how to use it, and then we had to develop the recipe step by step.”

The first step to keeping the samples clean was getting an enclosed chamber, called a glovebox. They filled the glovebox with argon gas, which is very unreactive, and worked with the BSCCO samples in it using gloves built into one of the walls.

This kept the sample away from the air, but unfortunately the crystal structure can alter even without outside gases. BSCCO crystals carry around oxygen atoms inside them. The oxygen isn’t locked into its structure and can cause problems even in an argon atmosphere. If a piece of BSCCO is warm, the oxygen atoms roam around the crystal, and eventually those near the surface escape, changing the electrical properties. Without the oxygen, the surface becomes insulating and prevents a good electrical connection between different layers or to wires needed for measurements. Even just a few minutes at room temperature between when the group peeled the layers apart and stacked two into a new orientation was enough to disrupt experiments.

Once, the group was discussing how to keep things cool and prevent the oxygen from creating issues, and someone suggested putting liquid nitrogen (which is around -321 degrees Fahrenheit) in the glovebox.

“I was like, ‘Oh, what are you talking about? No, we can't do that. That's crazy.’” Zhao recalls. “But then I thought, why not? Let's do it.’”

Trying the idea required modifying connections to the glove box to handle the frigid liquid nitrogen, but the crazy idea paid off. With the liquid nitrogen flowing, the temperature dropped to where clean samples could be assembled.

But a hurdle remained. They also needed to connect small electrical wires in a particular layout. The standard way for making small connections in precise patterns involves specialized processes that need to be done in a clean room and not the glovebox. Removing the samples from the glovebox would expose them to air and destroy all of Zhao’s hard work.

The solution Zhao and the group came up with was to go to the clean room and create the pattern of needed connections as a template of holes in another material. They took that template back to the glovebox and attached it to a sample. Then they performed a process that effectively let them spray paint gold onto the surface and through the holes in the template. This approach created the precise, clean connections needed to measure currents in the BSCCO samples—all without ever taking them out of the glove box.

With this recipe for putting together clean samples, Zhao was able to measure the superconducting currents in samples with different angles. He finally saw the dependence on the orientation of the layers and a dramatic drop in the current when they oriented the two layers with a 45-degree twist, validating the theoretical models.

The results also revealed some interesting behaviors in the slight superconducting current that remained for samples with the 45-degree orientations. Unlike most superconducting currents, the sample produced a different maximum superconducting current that it could maintain when Zhao flipped the direction of the current flowing across. He also observed that the maximum current depended on which direction had been used in the prior run. These measurements supported an idea that theorists have proposed: that the 45-degree orientation can produce a type of superconductivity called “high-temperature topological superconductivity,” which has properties that researchers have predicted will be useful in future technologies.

By finally making clean enough interfaces, Zhao and his colleagues were able to observe the physics of BSCCO instead of the interference of random contaminants. They described their results in an article published in the journal Science in Dec. 2023.

Besides revealing the properties of BSCCO, the results demonstrated the usefulness of the recipe Zhao and his colleagues had cooked up for stacking thin layers into clean samples. These techniques opened the way for Zhao to produce and study high-quality samples of many different materials that are otherwise difficult to stack cleanly.

After graduating from Harvard, Zhao went on to be a postdoctoral researcher in Joseph Checkelsky’s lab at MIT. There, he adapted a recipe that a graduate student in the lab had developed for growing large uniform crystals. The new recipe introduced the opportunity to make a variety of new layered materials with very clean structures. Zhao adjusted the recipe by substituting tantalum for niobium to make BaTa2S5 crystals and investigated if the slightly different material had any distinguishing properties.

“It's just a one element difference, but the physics is very different,” Zhao says.

The clean versions of BaTa2S5 produced were little black hexagons that naturally had thin alternating layers of superconductors and insulators. When Zhao investigated the material’s properties, he found some superconducting states that excited the team. Zhao’s experiments suggested that the material hosted a superconducting state that survived even in unusually high magnetic fields. That indicated the crystal could be an unconventional superconductor where electrons pair up together in a way that can be easily disrupted if the material’s structure isn’t just right but that is also more robust to magnetic fields than conventional superconductors.

“These unconventional superconductors tend to be very sensitive to disorder, and that's why to realize this material, we had to make it very clean,” Zhao says.

Having clean BaTa2S5 crystals now gives Zhao and other researchers a chance to study its superconductivity and investigate mysteries about how electrons pair up in different materials and possibly gain insight into superconductivity. At UMD, Zhao plans to continue studying superconductivity in BaTa2S5 crystals. Additionally, he is considering studying other materials with similar structures to see if they reveal interesting details about exotic ways superconductivity can arise.

As he settles in at UMD, Zhao is once again setting up a lab from scratch, but this time it is his own. In his new lab, he plans to continue to study both naturally formed crystals, like BaTa2S5, and manually stacked materials, like the twisted layers of BSCCO.

“Now we have some toolkits for making devices using any material that is exfoliable, and I have some toolkits on how to make single crystals,” Zhao says. “So now the goal is to combine them to make new devices.”

Zhao plans to use his skills at producing high-quality crystals to make materials that he can study in their natural bulk form and that he can use as sources of layers to build other samples. He says he is excited to join the excellent researchers at UMD as he pursues these projects.

“Honestly, this is one of the best places I can think of to do this kind of research, not to mention there are some really excellent theorists here as well to guide the research,” Zhao says. “One of the things I'm really hoping to do here is to contribute to a really collaborative environment.”

Written by Bailey Bedford