When senior physics major Zoe Schlossnagle arrived at the University of Maryland in fall 2021, she never could have imagined the opportunities she would seize.

“I was sure that I was going to receive a vigorous physics education, of course,” Schlossnagle said. “But I also ended up with these amazing, wildly different experiences that use my physics background in a way that goes beyond most normal classroom settings.”

Schlossnagle lugged around a sledgehammer to conduct ground tests on land degradation near the Anacostia River, trekked through the oppressive California summer heat—with highs of 115 degrees Fahrenheit—to examine mysterious landforms, and studied precursor solar flares from deep in space.

But her most recent research project truly captured her imagination: analyzing seismic activity in the ice sheets of Antarctica, one of the most remote places on Earth.

“I study Antarctic ice quakes, which are seismic events similar to earthquakes that happen in the ice,” Schlossnagle explained. “Those giant glaciers and ice shelves are usually pretty mysterious because we usually can’t physically see or access them in their entirety. Ice quakes let us ‘see’ their internal structure and dynamics. Studying them is crucial because ice instability can lead to sea-level rise, irreversible ice sheet collapse and the destruction of coastal communities and ecosystems.”

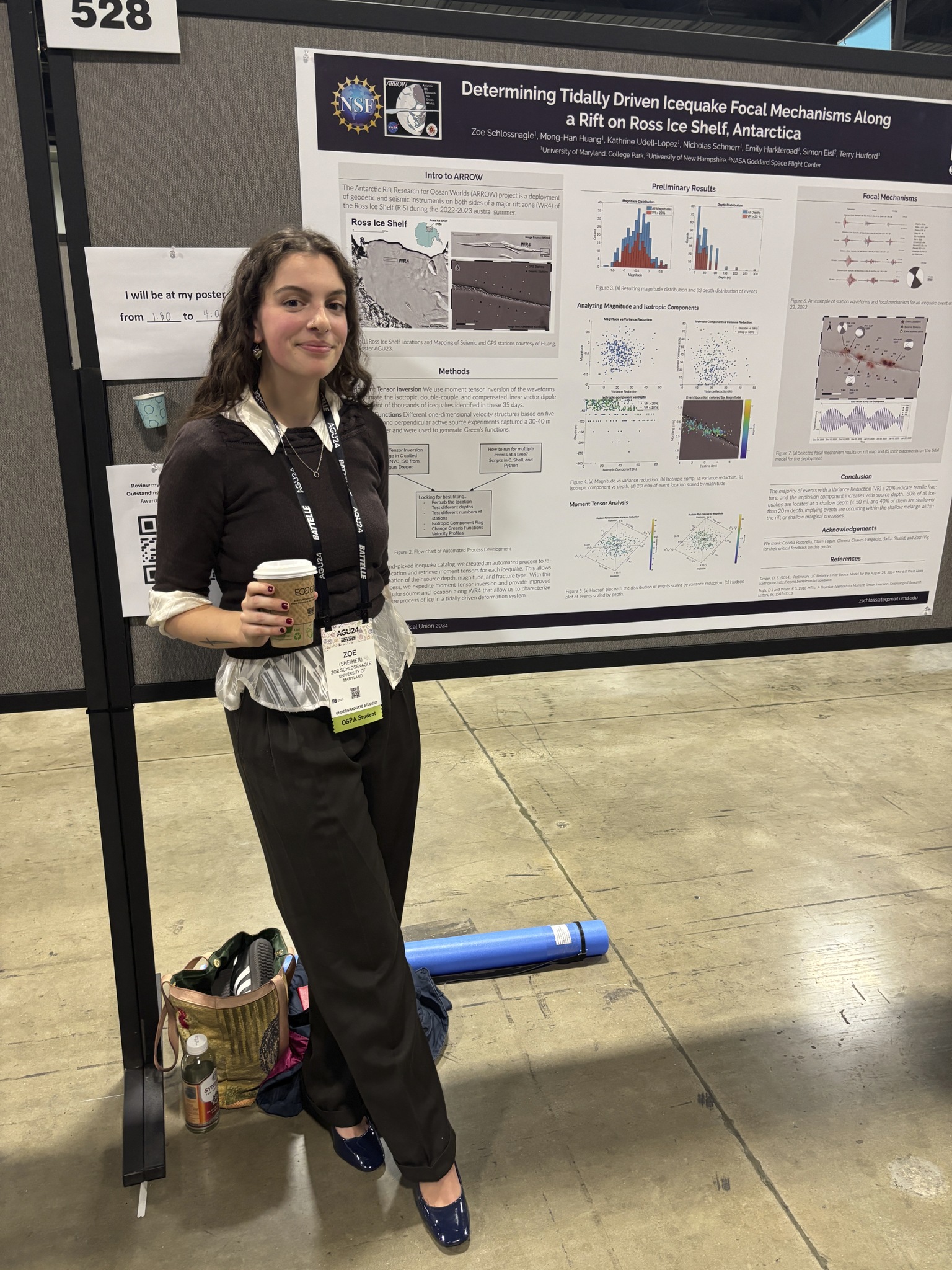

Zoe Schlossnagle presenting moment tensor research at American Geophysical Union, Dec 2024.Schlossnagle joined Associate Professor of Geology Mong-han Huang’s Active Tectonics Laboratory in 2024 to understand how ice moves based on seismic waves. The project began the year before when a team of researchers, including Huang, deployed and retrieved a set of seismometers (instruments that respond to ground displacement and shaking) on the Ross Ice Shelf, the largest ice shelf in Antarctica. The waves captured by the seismometers reflect and refract based on the material they travel through, which allows researchers to image the immediate subsurface without excavation.

Zoe Schlossnagle presenting moment tensor research at American Geophysical Union, Dec 2024.Schlossnagle joined Associate Professor of Geology Mong-han Huang’s Active Tectonics Laboratory in 2024 to understand how ice moves based on seismic waves. The project began the year before when a team of researchers, including Huang, deployed and retrieved a set of seismometers (instruments that respond to ground displacement and shaking) on the Ross Ice Shelf, the largest ice shelf in Antarctica. The waves captured by the seismometers reflect and refract based on the material they travel through, which allows researchers to image the immediate subsurface without excavation.

“I’m working on finding moment tensor solutions, which are mathematical ways to visualize and understand the forces that create earthquakes, for very low magnitude ice quakes,” Schlossnagle said. “Knowing what direction ice is slipping in—up and down, left to right—and where a quake’s focal point is can help us calculate things like where an ice shelf will be unstable or even how long we have until the sea level reaches a certain point.”

Though she does most of her work in Huang’s lab on campus, Schlossnagle said that her physics training has been invaluable to her research. Schlossnagle’s problem-solving mindset and the math skills developed in her physics studies helped her approach the challenges of dealing with massive quantities of data. In particular, she said PHYS 401: Quantum Physics and PHYS 404: Introduction to Thermodynamics and Statistical Mechanics played important roles in her research.

“Like quantum physicists, seismologists look at waves all day long,” Schlossnagle joked. “Having my physics background and learning how to apply those skills has been tremendously helpful. This work is extremely interdisciplinary and it’s definitely reflected in the people I work with—we’re all contributing what we know from different fields, from physics to geology to climate science, to solve mysteries hidden in the ice.”

Giving back to the community

Schlossnagle’s desire to give back to the “community that sparked [her] passion for research and problem-solving” led to a collaboration with Associate Research Professor of Physics Chandra Turpen. Together, they developed an extensive survey—inspired by the research-based approach to mental health taken by the UMD Physics Graduate Student Mental Health Task Force—to identify the unique challenges faced by undergraduates in STEM.

Schlossnagle said the survey explores everything from effective classroom practices for professors to helpful study techniques for students. She and Turpen hope that as they learn more about what undergraduate students experience in their studies, they can help bridge the gap between students and professors.

“Zoe has demonstrated excellent leadership skills and a commitment to transformative change in STEM higher education,” Turpen said. “I’m confident that she will continue to conduct innovative research, contribute to building inclusive research groups and positively shape the experiences of students around her.”

As her senior year draws to a close, Schlossnagle plans to continue her work on unraveling the mysteries of Earth’s frozen frontiers. She will pursue a Ph.D. in cryosphere geophysics in the fall, with a focus on improving ice sheet models and gaining new insight into just how quickly sea levels are changing.

“I think all my academic and extracurricular goals trace back to tackling problems that impact all of us universally,” Schlossnagle said. “And to me, that means we need interdisciplinary solutions from everyone as well.”