Researchers Measure Casimir Torque for the First Time

- Details

- Category: Research News

- Published: Thursday, December 20 2018 14:03

Physics researchers and members of the Institute for Research in Electronics and Applied Physics worked with the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering to measure for the first time an effect that was predicted more than 40 years ago, called the Casimir torque.

When placed together in a vacuum less than the diameter of a bacterium (one micron) apart, two pieces of metal attract each other. This is called the Casimir effect. The Casimir torque—a related phenomenon that is caused by the same quantum electromagnetic effects that attract the materials—pushes the materials into a spin. Because it is such a tiny effect, the Casimir torque has been difficult to study. The research team, which includes members from UMD's departments of electrical and computer engineering and physics and Institute for Research in Electronics and Applied Physics, has built an apparatus to measure the decades-old prediction of this phenomenon and published their results in the December 20th issue of the journal Nature.

"This is an interesting situation where industry is using something because it works, but the mechanism is not well-understood," said Jeremy Munday, the leader of the research. "For LCD displays, for example, we know how to create twisted liquid crystals, but we don't really know why they twist. Our study proves that the Casimir torque is a crucial component of liquid crystal alignment. It is the first to quantify the contribution of the Casimir effect, but is not the first to prove that it contributes."

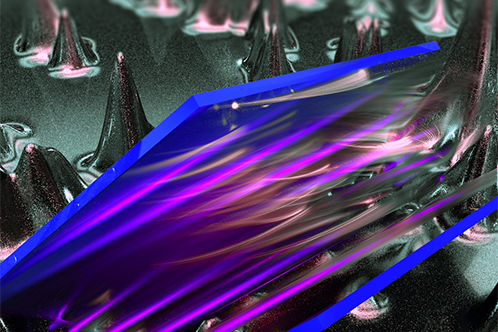

The device places a liquid crystal just tens of nanometers from a solid crystal. With a polarizing microscope, the researchers then observed how the liquid crystal twists to match the solid's crystalline axis.

The team used liquid crystals because they are very sensitive to external forces and can twist the light that passes through them. Under the microscope, each imaged pixel is either light or dark depending on how twisted the liquid crystal layer is. In the experiment, a faint change in the brightness of a liquid crystal layer allowed the research team to characterize the liquid crystal twist and the torque that caused it.

The Casimir effect could make nanoscale parts move and can be used to invent new nanoscale devices, such as actuators or motors.

"Think of any machine that requires a torque or twist to be transmitted: driveshafts, motors, etc.," said Munday. "The Casimir torque can do this on a nanoscale."

Knowing the amount of Casimir torque in a system can also help researchers understand the motions of nanoscale parts powered by the Casimir effect.

The team tested a few different types of solids to measure their Casimir torques, and found that each material has its own unique signature of Casimir torque.

The measurement devices were built in UMD's Fab Lab, a shared user facility and cleanroom housing tools to make nanoscale devices.

In the past, the researchers also made the first measurements of a repulsive Casimir force and a measurement of the Casimir force between two spheres. They have also made some predictions that could be confirmed if the current measurement technique can be refined; Munday reports they are testing other materials to control and tailor the torque.

Munday is an associate professor of electrical and computer engineering in UMD's A. James Clark School of Engineering, and his lab is housed in UMD's Institute for Research in Electronics and Applied Physics, which enables interdisciplinary research between its natural science and engineering colleges.

"Experiments like this are helping us better understand and control the quantum vacuum. It's what one might call 'the physics of empty space,' which upon closer examination seems to be not so empty after all," said John Gillaspy, the physics program officer who oversaw National Science Foundation funding of the research.

"Classically, the vacuum is really empty—it is, by definition, the absence of anything," said Gillaspy. "But quantum physics predicts that even the most empty space that one can imagine is filled with 'virtual' particles and fields, quantum fluctuations in pure emptiness that lead to subtle, but very real, effects that can be measured and even exploited to do things that would otherwise be impossible. The universe contains many complicated things, yet there are still unanswered questions about some of the simplest, most fundamental phenomena—this research may help us to find some of the answers."

Original story: https://energy.umd.edu/news/story/researchers-make-liquid-crystals-do-the-twist