Remote Quantum Systems Produce Interfering Photons

- Details

- Published: Wednesday, December 18 2019 02:53

UMD physicists have observed, for the first time, interference between particles of light created using a trapped ion and a collection of neutral atoms. Their results could be an essential step toward the realization of a distributed network of quantum computers capable of processing information in novel ways.

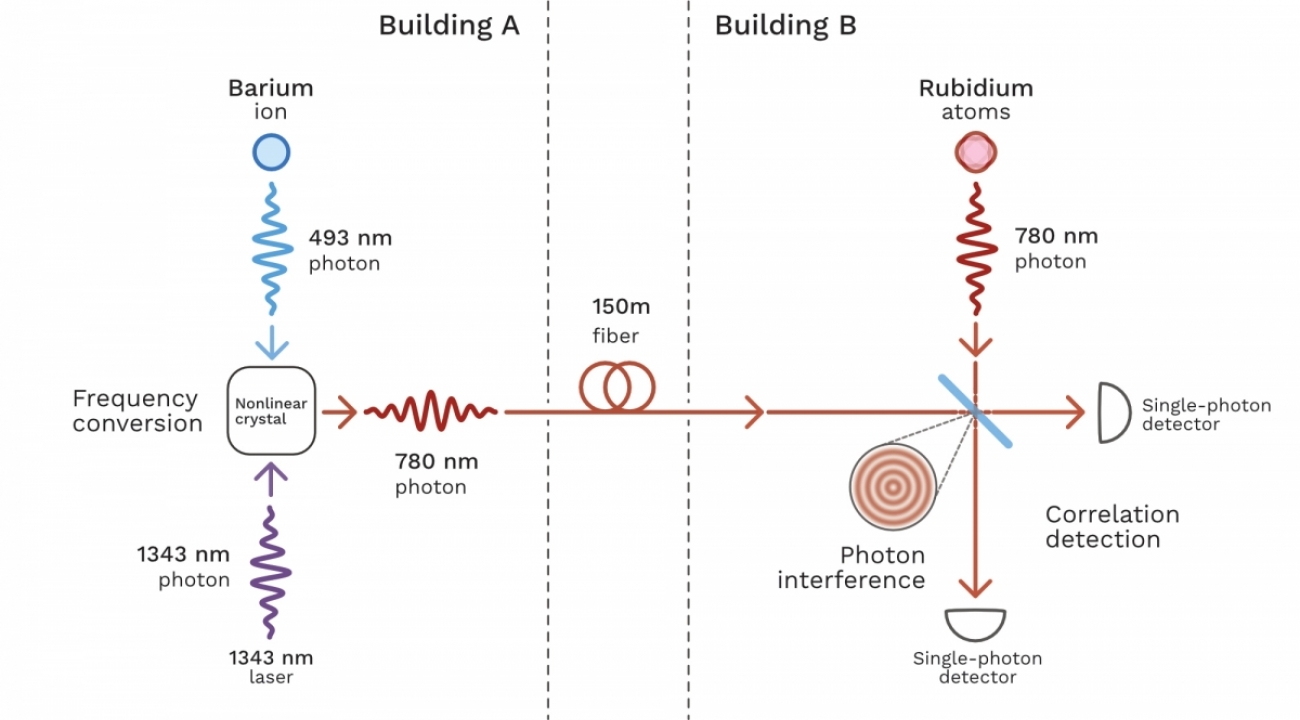

In the new experiment, atoms in neighboring buildings produced photons—the quantum particles of light—in two distinct ways. Several hundred feet of optical cables then brought the photons together, and the research team, which included scientists from the Joint Quantum Institute (JQI) as well as the Army Research Lab, measured a telltale interference pattern. It was the first time that photons from these two particular quantum systems were manipulated into having the same wavelength, energy and polarization—a feat that made the particles indistinguishable. The result, which may prove vital for communicating over quantum networks of the future, was published recently in the journal Physical Review Letters.

“If we want to build a quantum internet, we need to be able to connect nodes of different types and functions,” says JQI Fellow Steve Rolston, a co-author of the paper and a professor of physics at the University of Maryland. “Quantum interference between photons generated by the different systems is necessary to eventually entangle the nodes, making the network truly quantum.” A schematic showing the paths taken by photons from two different sources in neighboring buildings. (Credit: S. Kelley/NIST)

A schematic showing the paths taken by photons from two different sources in neighboring buildings. (Credit: S. Kelley/NIST)

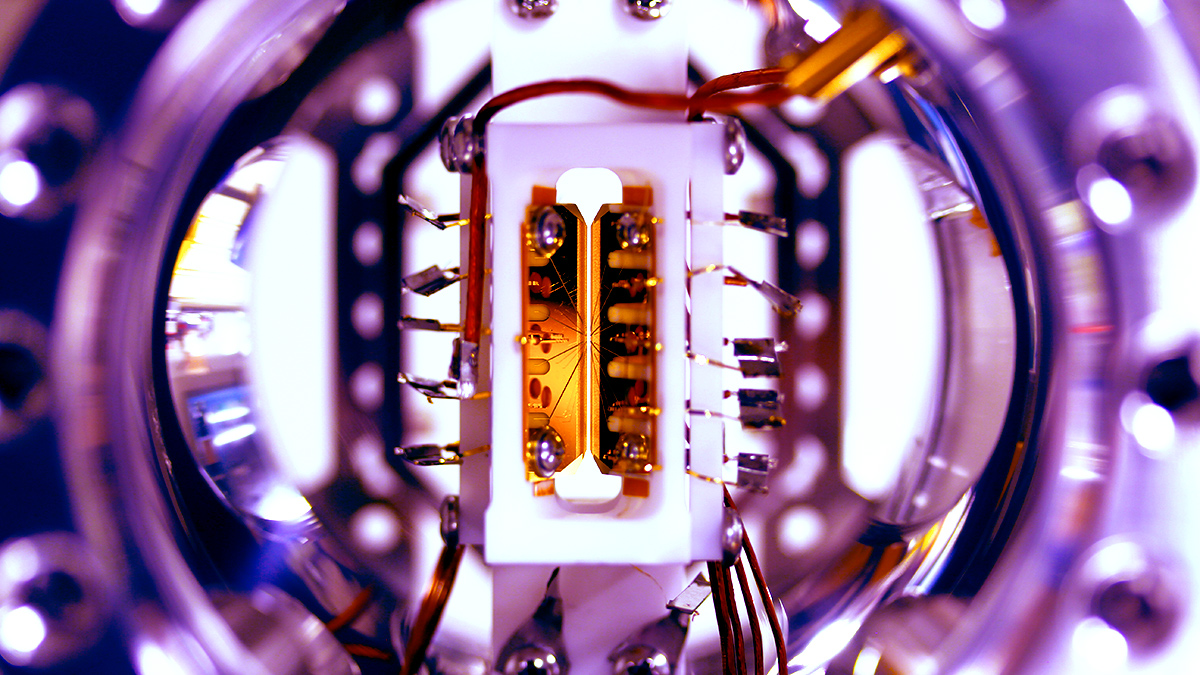

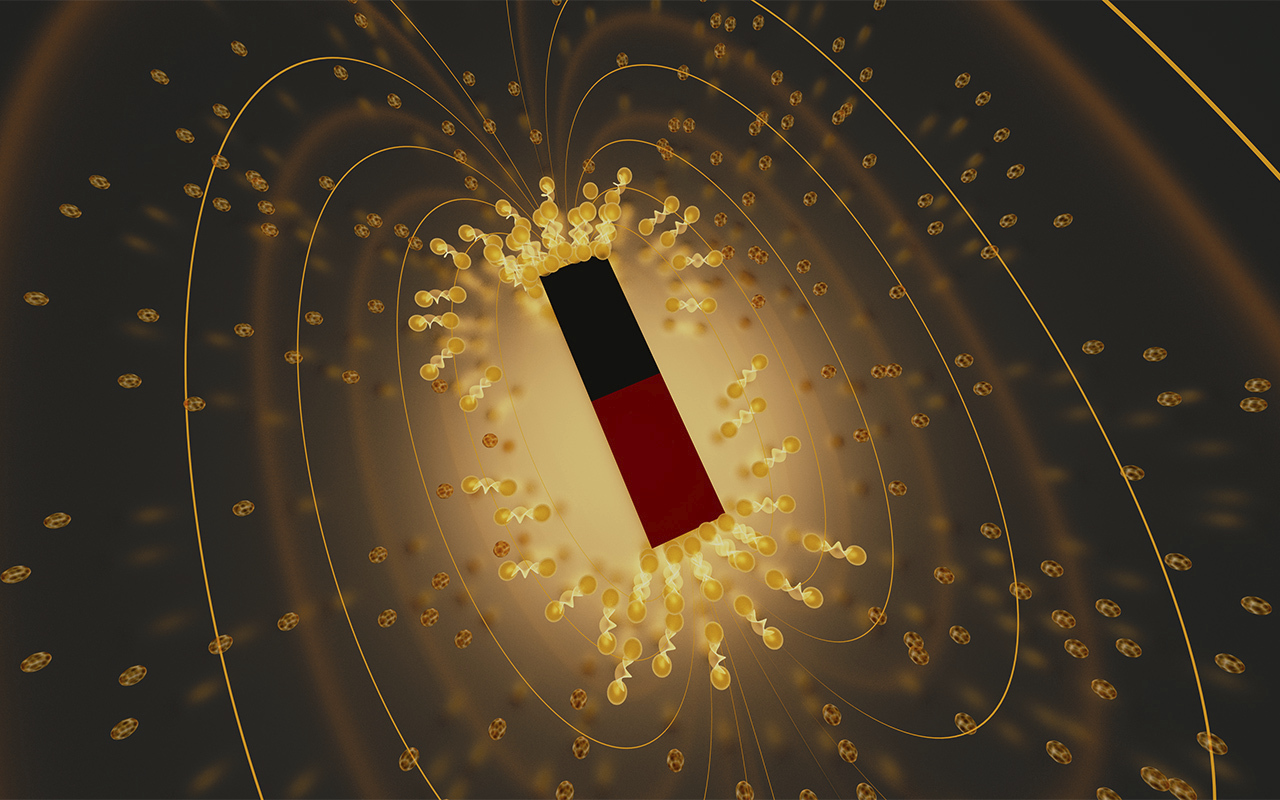

The first source of photons was a single trapped ion—an atom that is missing an electron—held in place by electric fields. Collections of these ions, trapped in a chain, are leading candidates for the construction of quantum computers due to their long lifetimes and ease of control. The second source of photons was a collection of very cold atoms, still in possession of all their electrons. These uncharged, or neutral, atomic ensembles are excellent interfaces between light and matter, as they easily convert photons into atomic excitations and vice versa. The photons produced by each of these two systems are typically different, limiting their ability to work together.

In one building, researchers used a laser to excite a trapped barium ion to a higher energy. When it transitioned back to a lower energy, it emitted a photon at a known wavelength but in a random direction. When scientists captured a photon, they stretched its wavelength to match photons from the other source.

In an adjacent building, a cloud of tens of thousands of neutral rubidium atoms generated the photons. Lasers were again used to pump up the energy of these atoms, and that procedure imprinted a single excitation across the whole cloud through a phenomenon called the Rydberg blockade. When the excitation shed its energy as photons, they traveled in a well-defined direction, making it easy for researchers to collect them.

The team used an interferometer to measure the degree to which two photons were identical. A single photon entering the interferometer is equally likely to take either of two possible exits. And two distinguishable photons entering the interferometer at the same time don’t notice each other, acting like two independent single photons.

But when researchers brought together the photons from their two sources, they almost always took the same exit—a result of quantum interference and an indication that they were nearly identical. This was precisely what the research team had hoped for: the first demonstration of interference between photons from these two very different quantum systems.

In this experiment, photons traveled from the first building to the second via hundreds of feet of optical fiber. Due to this distance, sending photons from both systems to meet at the interferometer simultaneously was a feat of precise timing. Detectors were placed at the exits of the interferometer to detect where the photons came out, but the team often had to wait—gathering all the data took 24 hours over a period of 3 days.

Further experimental upgrades could be used to generate a special quantum connection called entanglement between the ion and the neutral atoms. In entanglement, two quantum objects become so closely linked that the results from measuring one are correlated with the results from measuring the other, even if the objects are separated by a huge distance. Entanglement is necessary for the speedy algorithms that scientists hope to run on quantum computers in the future.

Generating entanglement between different quantum systems usually requires identical photons, which the researchers were able to create. Unfortunately, trapped ions emit photons in a random direction, making the probability of catching them low. This meant that only about eight photons from the trapped ion made it to the interferometer each second. If the researchers attempted to perform more intricate experiments with that rate, the data could take months to collect. However, future work may increase how frequently the ion emits photons and allow for a useful rate of entanglement production.

“This is a stepping-stone on the way to being able to entangle these two systems,” says Alexander Craddock, a graduate student at JQI and the lead author of this study. “And that would be fantastic, because you can then take advantage of all the different weird and wonderful properties of both of them.”

Story by Jillian Kunze

In addition to Rolston and Craddock, co-authors of the paper include JQI graduate students John Hannegan, Dalia Ornelas-Huerta, and Andrew Hachtel, JQI postdoctoral researcher James Siverns, Army Research Laboratory scientists and JQI Affiliates Elizabeth Goldschmidt (now an Assistant Professor of Physics at the University of Illinois) and Qudsia Quraishi, and JQI Fellow Trey Porto.