- Details

-

Published: Wednesday, March 28 2018 14:25

Editor's note: After further analysis of their experimental data, the authors of the paper highlighted in this story no longer claim that they measured a quantized conductance—the key experimental signature that would suggest the presence of Majorana fermions. The paper has been officially retracted. We have left this story up with this note because researchers believe the approach it describes remains a viable route to eventually detecting Majoranas.

In the latest experiment of its kind, researchers have captured the most compelling evidence to date that unusual particles lurk inside a special kind of superconductor. The result, which confirms theoretical predictions first made nearly a decade ago at the Joint Quantum Institute (JQI) and the University of Maryland (UMD),

In the latest experiment of its kind, researchers have captured the most compelling evidence to date that unusual particles lurk inside a special kind of superconductor. The result, which confirms theoretical predictions first made nearly a decade ago at the Joint Quantum Institute (JQI) and the University of Maryland (UMD), will be published in the April 5 issue of Nature.

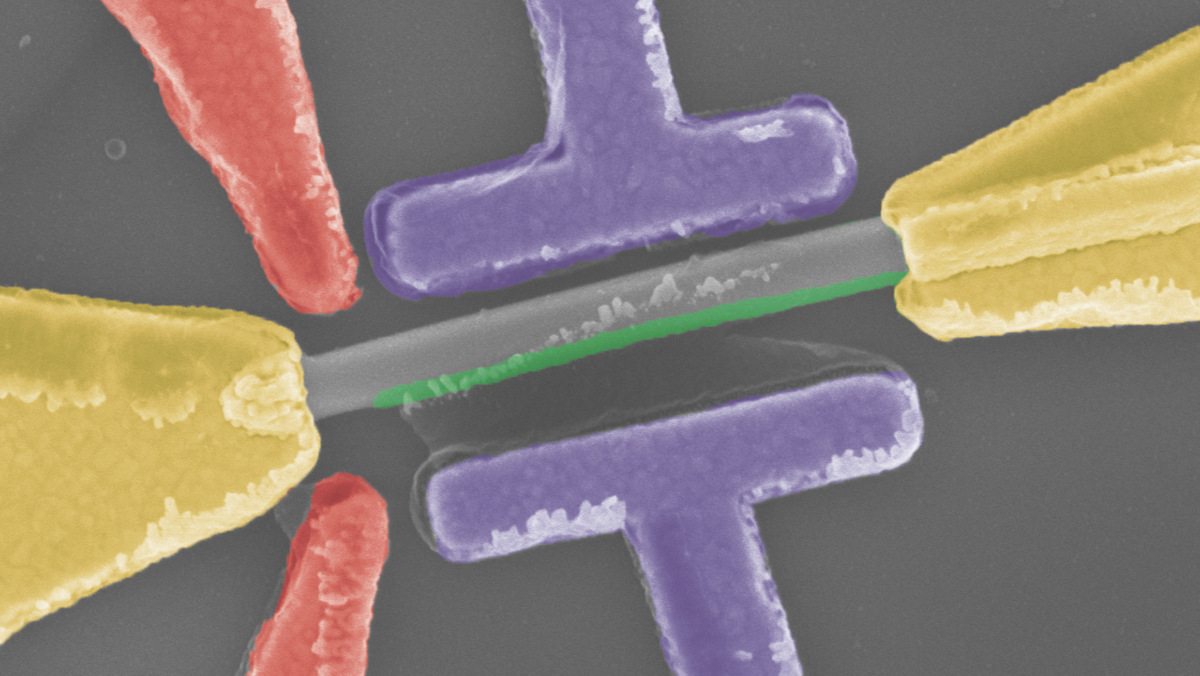

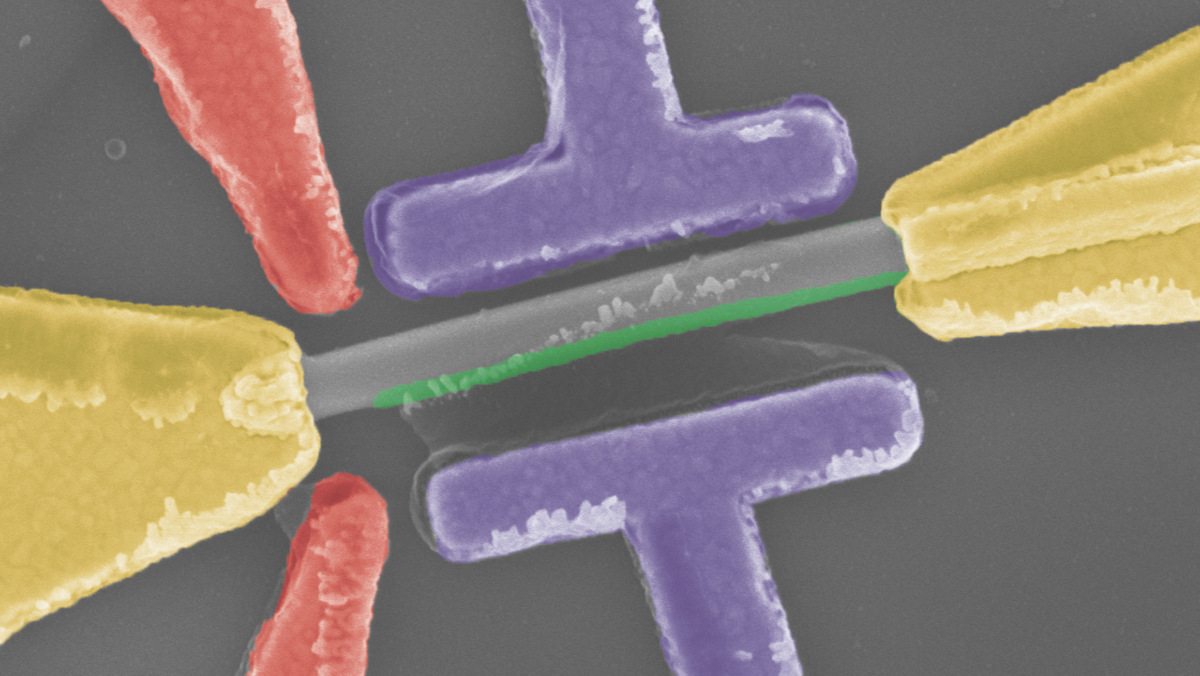

A device that physicists used to spot the clearest signal yet of Majorana particles. The gray wire in the middle is the nanowire, and the green area is a strip of superconducting aluminum. (Credit: Hao Zhang/QuTech)The stowaways, dubbed Majorana quasiparticles, are different from ordinary matter like electrons or quarks—the stuff that makes up the elements of the periodic table. Unlike those particles, which as far as physicists know can’t be broken down into more basic pieces, Majorana quasiparticles arise from coordinated patterns of many atoms and electrons and only appear under special conditions. They are endowed with unique features that may allow them to form the backbone of one type of quantum computer, and researchers have been chasing after them for years.

A device that physicists used to spot the clearest signal yet of Majorana particles. The gray wire in the middle is the nanowire, and the green area is a strip of superconducting aluminum. (Credit: Hao Zhang/QuTech)The stowaways, dubbed Majorana quasiparticles, are different from ordinary matter like electrons or quarks—the stuff that makes up the elements of the periodic table. Unlike those particles, which as far as physicists know can’t be broken down into more basic pieces, Majorana quasiparticles arise from coordinated patterns of many atoms and electrons and only appear under special conditions. They are endowed with unique features that may allow them to form the backbone of one type of quantum computer, and researchers have been chasing after them for years.

The latest result is the most tantalizing yet for Majorana hunters, confirming many theoretical predictions and laying the groundwork for more refined experiments in the future. In the new work, researchers measured the electrical current passing through an ultra-thin semiconductor connected to a strip of superconducting aluminum—a recipe that transforms the whole combination into a special kind of superconductor.

Experiments of this type expose the nanowire to a strong magnet, which unlocks an extra way for electrons in the wire to organize themselves at low temperatures. With this additional arrangement the wire is predicted to host a Majorana quasiparticle, and experimenters can look for its presence by carefully measuring the wire’s electrical response.

The new experiment was conducted by researchers from QuTech at the Technical University of Delft in the Netherlands and Microsoft Research, with samples of the hybrid material prepared at the University of California, Santa Barbara and Eindhoven University of Technology in the Netherlands. Experimenters compared their results to theoretical calculations by JQI Fellow Sankar Das Sarma and JQI graduate student Chun-Xiao Liu.

The same group at Delft saw hints of a Majorana in 2012, but the measured electrical effect wasn’t as big as theory had predicted. Now the full effect has been observed, and it persists even when experimenters jiggle the strength of magnetic or electric fields—a robustness that provides even stronger evidence that the experiment has captured a Majorana, as predicted in careful theoretical simulations by Liu.

"We have come a long way from the theoretical recipe in 2010 for how to create Majorana particles in semiconductor-superconductor hybrid systems," says Das Sarma, a coauthor of the paper who is also the director of the Condensed Matter Theory Center at UMD. "But there is still some way to go before we can declare total victory in our search for these strange particles."

The success comes after years of refinements in the way that researchers assemble the nanowires, leading to cleaner contact between the semiconductor wire and the aluminum strip. During the same time, theorists have gained insight into the possible experimental signatures of Majoranas—work that was pioneered by Das Sarma and several collaborators at UMD.

Theory meets experiment

The quest to find Majorana quasiparticles in thin quantum wires began in 2001, spurred by Alexei Kitaev, then a physicist then at Microsoft Research. Kitaev, who is now at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, concocted a relatively simple but unrealistic system that could theoretically harbor a Majorana. But this imaginary wire required a specific kind of superconductivity not available off-the-shelf from nature, and others soon began looking for ways to imitate Kitaev’s contraption by mixing and matching available materials.

One challenge was figuring out how to get superconductors, which usually go about their business with an even number of electrons—two, four, six, etc.—to also allow an odd number of electrons, a situation that is normally unstable and requires extra energy to maintain. The odd number is necessary because Majorana quasiparticles are unabashed oddballs: They only show up in the coordinated behavior of an odd number of electrons.

In 2010, almost a decade after Kitaev’s original paper, Das Sarma, JQI Fellow Jay Deep Sau and JQI postdoctoral researcher Roman Lutchyn, along with a second group of researchers, struck upon a method to create these special superconductors, and it has driven the experimental search ever since. They suggested combining a certain kind of semiconductor with an ordinary superconductor and measuring the current through the whole thing. They predicted that the combination of the two materials, along with a strong magnetic field, would unlock the Majorana arrangement and yield Kitaev’s special material.

They also predicted that a Majorana could reveal itself in the way current flows through such a nanowire. If you connect an ordinary semiconductor to a metal wire and a battery, electrons usually have some chance of hopping off the wire onto the semiconductor and some chance of being rebuffed—the details depend on the electrons and the makeup of the material. But if you instead use one of Kitaev’s nanowires, something completely different happens. The electron always gets perfectly reflected back into the wire, but it’s no longer an electron. It becomes what scientists call a hole—basically a spot in the metal that’s missing an electron—and it carries a positive charge back in the opposite direction.

Physics demands that the current across the interface be conserved, which means that two electrons must end up in the superconductor to balance out the positive charge heading in the other direction. The strange thing is that this process, which physicists call perfect Andreev reflection, happens even when electrons in the metal receive no push toward the boundary—that is, even when they aren’t hooked up to a battery of sorts. This is related to the fact that a Majorana is its own antiparticle, meaning that it doesn’t cost any energy to create a pair of Majoranas in the nanowire. The Majorana arrangement gives the two electrons some extra room to maneuver and allows them to traverse the nanowire as a quantized pair—that is, exactly two at a time.

"It is the existence of Majoranas that gives rise to this quantized differential conductance," says Liu, who ran numerical simulations to predict the results of the experiments on UMD’s Deepthought2 supercomputer cluster. "And such a quantization should even be robust to small changes in experimental parameters, as the real experiment shows."

Scientists refer to this style of experiment as tunneling spectroscopy because electrons are taking a quantum route through the nanowire to the other side. It has been the focus of recent efforts to capture Majoranas, but there are other tests that could more directly reveal the exotic properties of the particles—tests that would fully confirm that the Majoranas are really there.

"This experiment is a big step forward in our search for these exotic and elusive Majorana particles, showing the great advance made in the materials improvement over the last five years," Das Sarma says. "I am convinced that these strange particles exist in these nanowires, but only a non-local measurement establishing the underlying physics can make the evidence definitive."

By Chris Cesare

Original story.