Quantum Computers Are Starting to Simulate the World of Subatomic Particles

- Details

- Category: Research News

- Published: Tuesday, May 24 2022 02:46

There is a heated race to make quantum computers deliver practical results. But this race isn't just about making better technology—usually defined in terms of having fewer errors and more qubits, which are the basic building blocks that store quantum information. At least for now, the quantum computing race requires grappling with the complex realities of both quantum technologies and difficult problems. To develop quantum computing applications, researchers need to understand a particular quantum technology and a particular challenging problem and then adapt the strengths of the technology to address the intricacies of the problem.

Assistant Professor Zohreh Davoudi, a member of the Maryland Center for Fundamental Physics, has been working with multiple colleagues at UMD to ensure that the problems that she cares about are among those benefiting from early advances in quantum computing. The best modern computers have often proven inadequate at simulating the details that nuclear physicists need to understand our universe at the deepest levels.

Davoudi and JQI Fellow Norbert Linke are collaborating to push the frontier of both the theories and technologies of quantum simulation through research that uses current quantum computers. Their research is intended to illuminate a path toward simulations that can cut through the current blockade of fiendishly complex calculations and deliver new theoretical predictions. For example, quantum simulations might be the perfect tool for producing new predictions based on theories that combine Einstein’s theory of special relativity(link is external) and quantum mechanics to describe the basic building blocks of nature—the subatomic particles and the forces among them—in terms of “quantum fields(link is external).” Such predictions are likely to reveal new details about the outcomes of high-energy collisions in particle accelerators and other lingering physics questions.

Current quantum computers, utilizing technologies like the trapped ion device on the left, are beginning to tackle problems theoretical physicists care about, like simulating particle physics models. More than 60 years ago, the physicist Julian Schwinger laid the foundation for describing the relativistic and quantum mechanical behaviors of subatomic particles and the forces among them, and now his namesake model is serving as an early challenge for quantum computers. (Credit: Z. Davoudi/UMD with elements adopted from Emily Edwards/JQI (trapped ion device), Dizzo via Getty Images (abstract photon rays), and CERN (Schwinger photo)

Current quantum computers, utilizing technologies like the trapped ion device on the left, are beginning to tackle problems theoretical physicists care about, like simulating particle physics models. More than 60 years ago, the physicist Julian Schwinger laid the foundation for describing the relativistic and quantum mechanical behaviors of subatomic particles and the forces among them, and now his namesake model is serving as an early challenge for quantum computers. (Credit: Z. Davoudi/UMD with elements adopted from Emily Edwards/JQI (trapped ion device), Dizzo via Getty Images (abstract photon rays), and CERN (Schwinger photo) The team’s current efforts might help nuclear physicists, including Davoudi, to take advantage of the early benefits of quantum computing instead of needing to rush to catch up when quantum computers hit their stride. For Linke, who is also an assistant professor of physics at UMD, the problems faced by nuclear physicists provide a challenging practical target to take aim at during these early days of quantum computing.

In a new paper in PRX Quantum(link is external), Davoudi, Linke and their colleagues have combined theory and experiment to push the boundaries of quantum simulations—testing the limits of both the ion-based quantum computer in Linke’s lab and proposals for simulating quantum fields. Both Davoudi and Linke are also part of the NSF Quantum Leap Challenge Institute for Robust Quantum Simulation that is focused on exploring the rich opportunities presented by quantum simulations.

The new project wasn’t about adding more qubits to the computer or stamping out every source of error. Rather, it was about understanding how current technology can be tested against quantum simulations that are relevant to nuclear physicists so that both the theoretical proposals and the technology can progress in practical directions. The result was both a better quantum computer and improved quantum simulations of a basic model of subatomic particles

“I think for the current small and noisy devices, it is important to have a collaboration of theorists and experimentalists so that we can implement useful quantum simulations,” says JQI graduate student Nhung Nguyen, who was the first author of the paper. “There are many things we could try to improve on the experimental sides but knowing which one leaves the greatest impact on the result helps guides us in the right direction. And what makes the biggest impact depends a lot on what you try to simulate.”

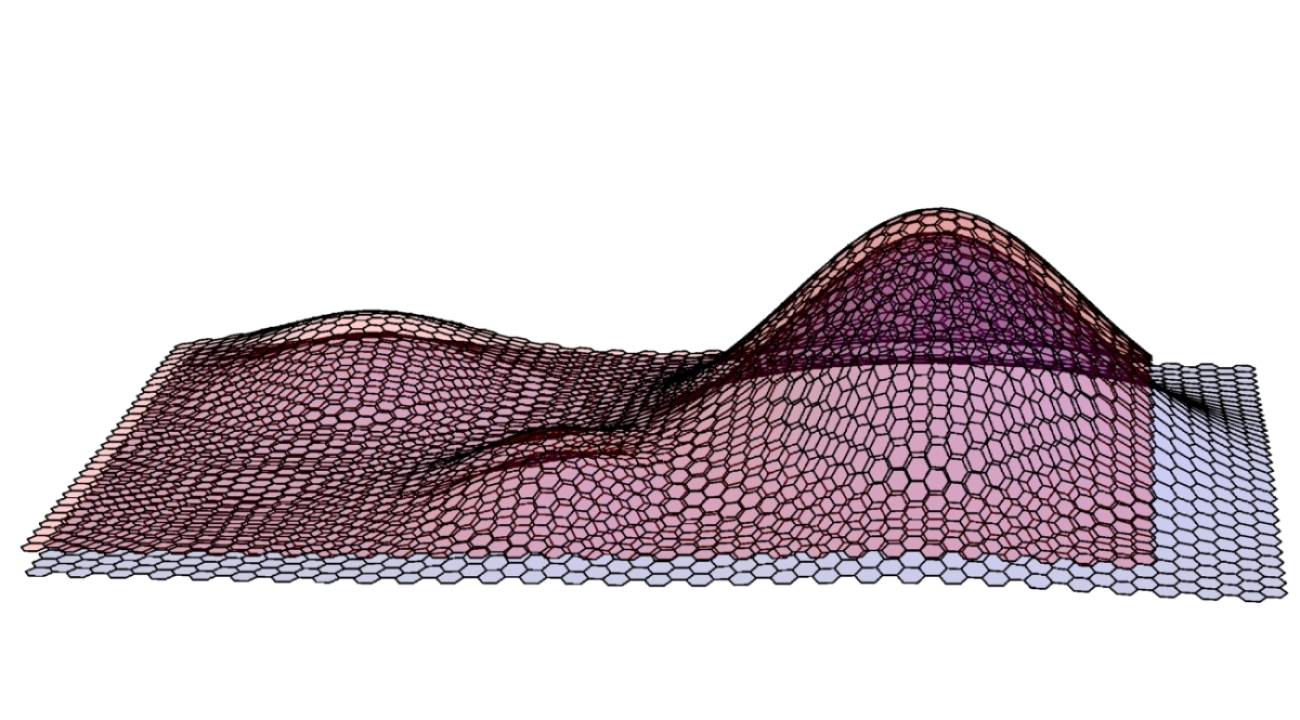

The team knew the biggest and most rewarding challenges in nuclear physics are beyound the reach of current hardware, so they started with something a little simpler than reality: the Schwinger model. Instead of looking at particles in reality’s three dimensions evolving over time, this model pares things down to particles existing in just one dimension over time. The researchers also further simplified things by using a version of the model that breaks continuous space into discrete sites. So in their simulations, space only exist as one line of distinct sites, like a column cut off a chess board, and the particles are like pieces that must always reside in one square or another along that column.

Despite the model being stripped of so much of reality’s complexity, interesting physics can still play out in it. The physicist Julian Schwinger developed this simplified model of quantum fields to mimic parts of physics that are integral to the formation of both the nuclei at the centers of atoms and the elementary particles that make them up.

“The Schwinger model kind of hits the sweet spot between something that we can simulate and something that is interesting,” says Minh Tran, a MIT postdoctoral researcher and former JQI graduate student who is a coauthor on the paper. “There are definitely more complicated and more interesting models, but they're also more difficult to realize in the current experiments.”

In this project, the team looked at simulations of electrons and positrons(link is external)—the antiparticles of electrons—appearing and disappearing over time in the Schwinger model. For convenience, the team started the simulation with an empty space—a vacuum. The creation and annihilation of a particle and its antiparticle out of vacuum is one of the significant predictions of quantum field theory. Schwinger’s work establishing this description of nature earned him, alongside Richard Feynman and Sin-Itiro Tomonaga, the Nobel Prize in physics in 1965(link is external). Simulating the details of such fundamental physics from first principles is a promising and challenging goal for quantum computers.

Nguyen led the experiment that simulated Schwinger’s pair production on the Linke Lab quantum computer, which uses ions—charged atoms—as the qubits.

“We have a quantum computer, and we want to push the limits,” Nguyen says. “We want to see if we optimize everything, how long can we go with it and is there something we can learn from doing the experimental simulation.”

The researchers simulated the model using up to six qubits and a preexisting language of computing actions called quantum gates. This approach is an example of digital simulation. In their computer, the ions stored information about if particles or antiparticles exist at each site in the model, and interactions were described using a series of gates that can change the ions and let them influence each other.

In the experiments, the gates only manipulated one or two ions at a time, so the simulation couldn’t include everything in the model interacting and changing simultaneously. The reality of digital simulations demands the model be chopped into multiple pieces that each evolve over small steps in time. The team had to figure out the best sequence of their individual quantum gates to approximate the model changing continuously over time.

“You're just approximately applying parts of what you want to do bit by bit,” Linke says. “And so that's an approximation, but all the orderings—which one you apply first, and which one second, etc.—will approximate the same actual evolution. But the errors that come up are different from different orderings. So there's a lot of choices here.”

Many things go into making those choices, and one important factor is the model’s symmetries. In physics, a symmetry(link is external) describes a change that leaves the equations of a model unchanged. For instance, in our universe rotating only changes your perspective and not the equations describing gravity, electricity or magnetism. However, the equations that describe specific situations often have more restrictive symmetries. So if an electron is alone in space, it will see the same physics in every direction. But if that electron is between the atoms in a metal, then the direction matters a lot: Only specific directions look equivalent. Physicists often benefit from considering symmetries that are more abstract than moving around in space, like symmetries about reversing the direction of time.

The Schwinger model makes a good starting point for the team’s line of research because of how it mimics aspects of complex nuclear dynamics and yet has simple symmetries.

“Once we aim to simulate the interactions that are in play in nuclear physics, the expression of the relevant symmetries is way more complicated and we need to be careful about how to encode them and how to take advantage of them,” Davoudi says. “In this experiment, putting things on a one-dimensional grid is only one of the simplifications. By adopting the Schwinger model, we have also a greatly simplified the notion of symmetries, which end up becoming a simple electric charge conservation. In our three-dimensional reality though, those more complicated symmetries are the reason we have bound atomic nuclei and hence everything else!”

The Schwinger model’s electric charge conservation symmetry keeps the total amount of electric charge the same. That means that if the simulation of the model starts from the empty state, then an electron should always be accompanied by a positron when it pops into or out of existence. So by choosing a sequence of quantum gates that always maintains this rule, the researchers knew that any result that violated it must be an error from experimental imperfections. They could then throw out the obviously bad data—a process called post-selection. This helped them avoid corrupted data but required more runs than if the errors could have been prevented.

The team also explored a separate way to use the Schwinger model’s symmetries. There are orders of the simulation steps that might prove advantageous despite not obeying the model’s symmetry rules. So suppressing errors that result from orderings that don’t conform to the symmetry could prove useful. Earlier this year, Tran and colleagues at JQI showed(link is external) there is a way to cause certain errors, including ones from a symmetry defying order of steps, to interfere with each other and cancel out.

The researchers applied the proposed procedure in an experiment for the first time. They found that it did decrease errors that violated the symmetry rules. However, due to other errors in the experiment, the process didn’t generally improve the results and overall was not better than resorting to post-selection. The fact that this method didn’t work well for this experiment provided the team with insights into the errors occurring during their simulations.

All the tweaking and trial and error paid off. Thanks to the improvements the researchers made, including upgrading the hardware and implementing strategies like post-selection, they increased how much information they could get from the simulation before it was overwhelmed by errors. The experiment simulated the Schwinger model evolving for about three times longer than previous quantum simulations. This progress meant that instead of just seeing part of a cycle of particle creation and annihilation in the Schwinger model, they were able to observe multiple complete cycles.

“What is exciting about this experiment for me is how much it has pushed our quantum computer forward,” says Linke. “A computer is a generic machine—you can do basically anything on it. And this is true for a quantum computer; there are all these various applications. But this problem was so challenging, that it inspired us to do the best we can and upgrade our system and go in new directions. And this will help us in the future to do more.”

There is still a long road before the quantum computing race ends, and Davoudi isn’t betting on just digital simulations to deliver the quantum computing prize for nuclear physicists. She is also interested in analog simulations and hybrid simulations that combine digital and analog approaches. In analog simulations, researchers directly map parts of their model onto those of an experimental simulation. Analog quantum simulations generally require fewer computing resources than their digital counterparts. But implementing analog simulations often requires experimentalists to invest more effort in specialized preparation since they aren’t taking advantage of a set of standardized building blocks that has been preestablished for their quantum computer.

Moving forward, Davoudi and Linke are interested in further research on more efficient mappings onto the quantum computer and possibly testing simulations using a hybrid approach they have proposed(link is external). In this approach, they would replace a particularly challenging part of the digital mapping by using the phonons—quantum particles of sound—in Linke Lab’s computer as direct stand-ins for the photons—quantum particles of light—in the Schwinger model and other similar models in nuclear physics.

“Being able to see that the kind of theories and calculations that we do on paper are now being implemented in reality on a quantum computer is just so exciting,” says Davoudi. “I feel like I'm in a position that in a few decades, I can tell the next generations that I was so lucky to be able to do my calculations on the first generations of quantum computers. Five years ago, I could have not imagined this day.”

Original story by Bailey Bedford: https://jqi.umd.edu/news/quantum-computers-are-starting-simulate-world-subatomic-particles