HAWC’s Measurement of the Highest Energy Photons Sets Limits on Violations of Relativity

- Details

- Published: Tuesday, March 31 2020 14:31

New measurements confirm, to the highest energies yet explored, that the laws of physics hold no matter where you are or how fast you're moving. Observations of record-breaking gamma rays prove the robustness of Lorentz Invariance—a piece of Einstein's theory of relativity that predicts the speed of light is constant everywhere in the universe. The High Altitude Water Cherenkov observatory in Puebla, Mexico detected the gamma rays coming from distant galactic sources. UMD authors on the paper were Jordan Goodman, Andy Smith, Bob Ellsworth, Kristi Engel, Israel Martinez-Castellanos, Michael Schneider and Elijah Tabachnick.

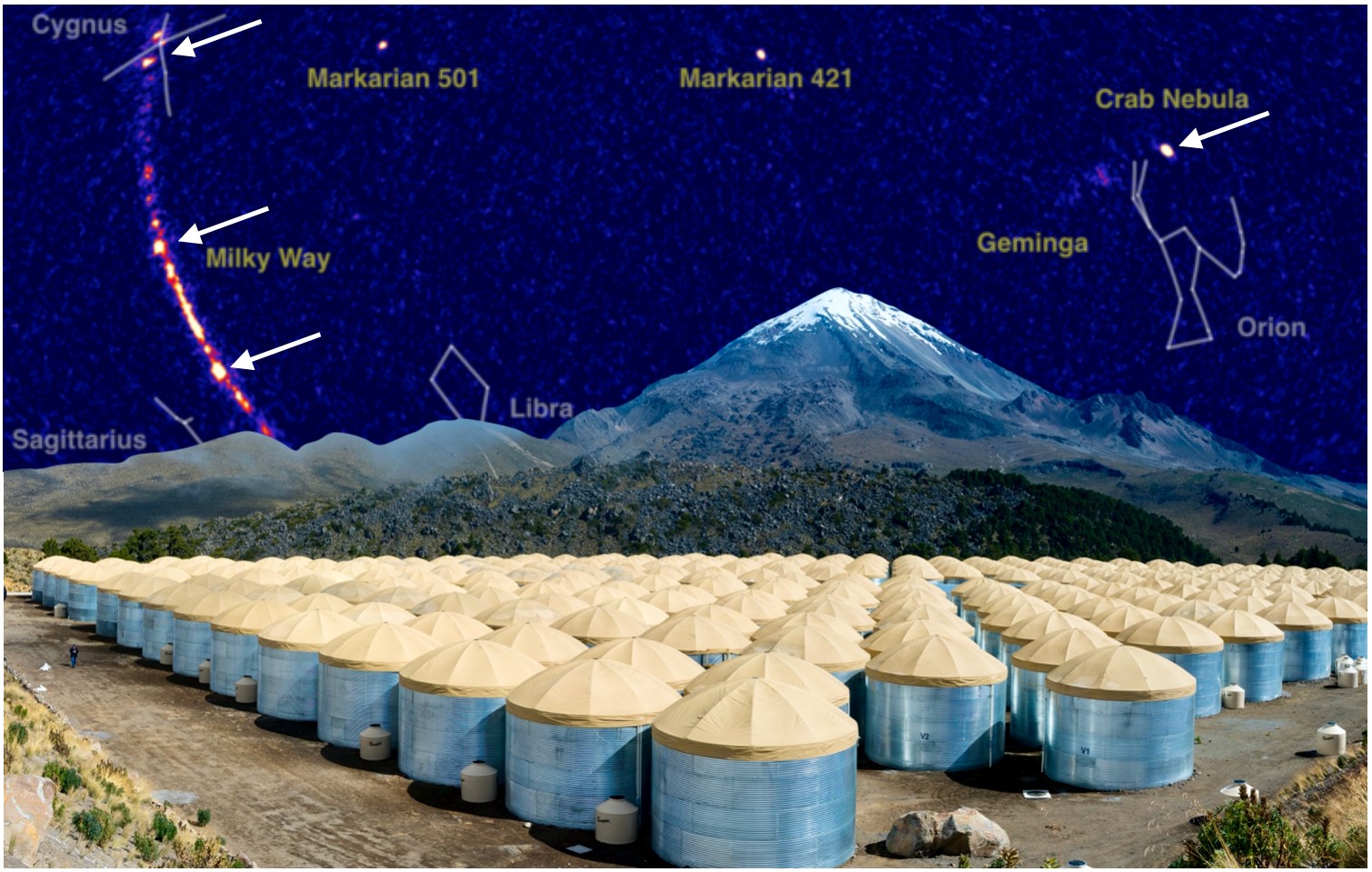

This compound graphic shows a view of the sky in ultra-high energy gamma rays. The arrows indicate the four sources of gamma rays with energies over 100 TeV from within our galaxy (courtesy of the HAWC collaboration) imposed over a photo of the HAWC Observatory’s 300 large water tanks. The tanks contain sensitive light detectors that measure showers of particles produced by the gamma rays striking the atmosphere more than 10 miles overhead. Credit: Jordan Goodman

This compound graphic shows a view of the sky in ultra-high energy gamma rays. The arrows indicate the four sources of gamma rays with energies over 100 TeV from within our galaxy (courtesy of the HAWC collaboration) imposed over a photo of the HAWC Observatory’s 300 large water tanks. The tanks contain sensitive light detectors that measure showers of particles produced by the gamma rays striking the atmosphere more than 10 miles overhead. Credit: Jordan Goodman

"How relativity behaves at very high energies has real consequences for the world around us," said Pat Harding, an astrophysicist in the Neutron Science and Technology group at Los Alamos National Laboratory and a member of the HAWC scientific collaboration. "Most quantum gravity models say the behavior of relativity will break down at very high energies. Our observation of such high-energy photons at all raises the energy scale where relativity holds by more than a factor of a hundred."

Lorentz Invariance is a key part of the Standard Model of physics. However, a number of theories about physics beyond the Standard Model suggest that Lorentz Invariance may not hold at the highest energies. If Lorentz Invariance is violated, a number of exotic phenomena become possibilities. For example, gamma rays might travel faster or slower than the conventional speed of light. If faster, those high-energy photons would decay into lower-energy particles and thus never reach Earth.

The HAWC Gamma Ray Observatory has recently detected a number of astrophysical sources which produce photons above 100 TeV (a trillion times the energy of visible light), much higher energy than is available from any earthly accelerator. Because HAWC sees these gamma rays, it extends the range that Lorentz Invariance holds by a factor of 100 times.

"Detections of even higher-energy gamma rays from astronomical distances will allow more stringent the checks on relativity. As HAWC continues to take more data in the coming years and incorporate Los Alamos-led improvements to the detector and analysis techniques at the highest energies, we will be able to study this physics even further," said Harding.

Story courtesy of Los Alamos National Laboratory. Article: https://journals.aps.org/prl/abstract/10.1103/PhysRevLett.124.131101

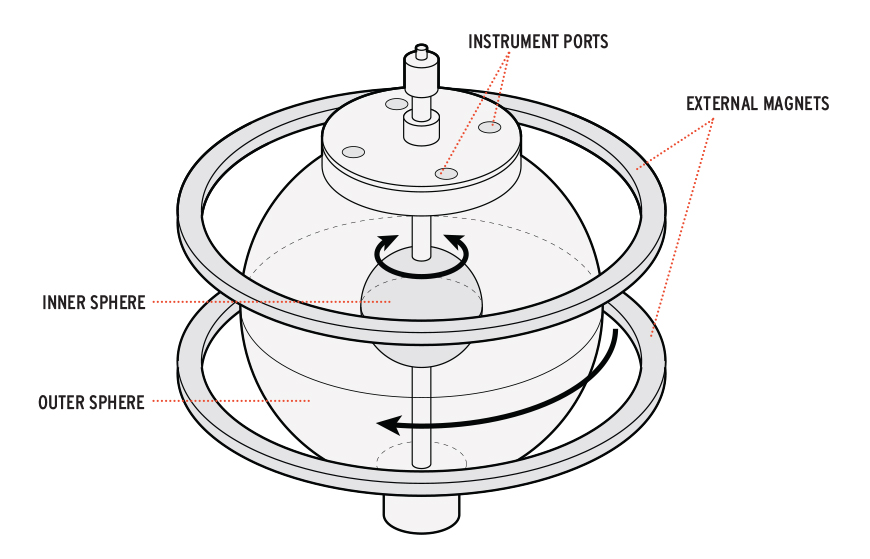

eodynamo,” a self-generating, self-sustaining magnetic field created by flows in its molten outer core, a layer of mostly iron and nickel more than 3,000 kilometers beneath our feet. Swirling turbulence in the liquid metal, caused by convection and the planet’s rotation, gives rise to electrical currents and magnetic fields that feed on each other.

eodynamo,” a self-generating, self-sustaining magnetic field created by flows in its molten outer core, a layer of mostly iron and nickel more than 3,000 kilometers beneath our feet. Swirling turbulence in the liquid metal, caused by convection and the planet’s rotation, gives rise to electrical currents and magnetic fields that feed on each other.