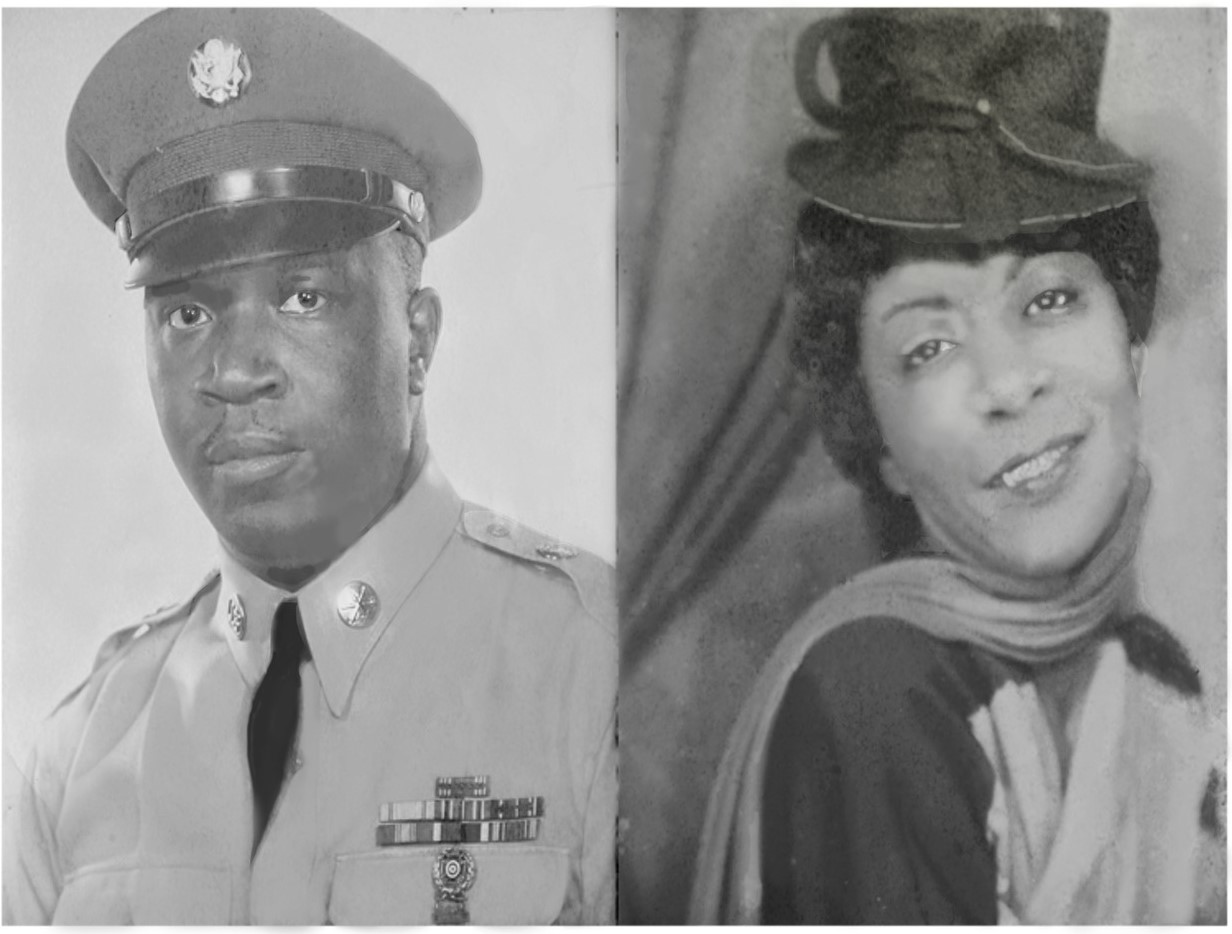

Jesse Anderson Retires Following 34-Year Career in the Department

- Details

- Category: Department News

- Published: Tuesday, March 15 2022 00:01

As he finished his career in the Army with a posting at the old Walter Reed Hospital in Northwest Washington, Jesse James Anderson decided to enroll at the nearby University of Maryland in College Park in 1983. Ever industrious, he took two jobs: one as a carpenter in residential services, and another at the Stamp Student Union information desk. One day, in a Stamp elevator, a friend dared him to talk to a female student sharing the lift. “And I did,” says Anderson, recalling the day he met his wife Danna. “It worked out well for us.”

Danna Anderson studied in College Park for two years before transferring to the University of Maryland, Baltimore, to pursue her degree in medical technology. The couple moved to Charm City, where they have resided ever since. When she completed her practicum at Johns Hopkins University, Danna was immediately offered a staff position, and now supervises the Core Lab at JHU Hospital.

Despite the distance, Jesse Anderson chose to stick with UMD. He spotted and applied for a job in the physics machine shop, and was hired as a storekeeper under manager Frank Desrosier. “I was studying electrical engineering and learning applied math, which made the shop stuff fun,” he said. “I was very interested in scientific methods and materials, and I learned a lot about metals.” Over the course of a decade managing the Physics Material Store, he switched his studies to industrial technology, learning machining, drafting and lathe work, all of which he found intriguing and refreshing after his seven years in the Army, which were spent in somewhat monotonous finance and accounting work. Steve Rolston and Jesse Anderson at the 2018 staff awards.

Steve Rolston and Jesse Anderson at the 2018 staff awards.

But military service had imparted meticulous record keeping habits that caught the attention of the physics purchasing manager, Camille Vogts. “I think she liked my paperwork,” chuckled Anderson. Vogts was often invited to vendor expos, which she regularly asked Anderson to attend. He recalls these outings as highlights of his UMD years, as they featured up-and-coming, whiz-bang technological developments in machining and laboratory devices. “Those shows were amazing to see,” Anderson recalls.

When an opening arose in the physics receiving office, personnel director Lorraine DeSalvo urged Anderson to apply. “I watched when he first arrived as the storekeeper in the shop,” said DeSalvo. “You just know when you see that sparkle in someone, that willingness and even eagerness to take on some new responsibilities.”

During his stint in receiving, Jesse and Danna enjoyed a four-week vacation, traveling to California to see Jesse’s brother. Upon his return, he found that business director Dean Kitchen had decided to expand his duties. “Dean said, ‘Well, if you’re good with receiving, you can likely handle purchasing, too,’” Anderson recalled. And after the sudden death of purchasing manager Bob Dahms in 2013, Anderson’s purview expanded further.

From that time until his retirement in December 2021, Anderson faced a relentless workload that included the dizzying logistics of the 2014 move into the Physical Sciences Complex and the resultant need to coordinate purchasing, shipping and receiving for loading docks in separate buildings, ensuring a very busy life. And then, in March 2020, the campus abruptly ceased operations for all save a few staffers. Staying home was not an option for Anderson. During the COVID-19 shutdown, he continued to come to campus daily in support of the department.

“COVID was a lot,” Anderson said. “Managing the loading docks, sending up the mailed paychecks, dealing with the picked-up-in-person paychecks. Just a lot to manage.” Al Godinez, who staffed the Toll Building loading dock for many years, retired in December 2020. “Al urged me to consider retiring, too, but that would have been hard on the department,” Anderson said. And so he persevered for another year, until more normal operations were underway and a replacement could be hired.

For his efforts during the shutdown, Anderson received the first Lorraine DeSalvo Chair's Endowed Award for Outstanding Service, presented virtually by physics chair Steve Rolston in December, 2020.

“Jesse is amazing,” DeSalvo said. “He was always there, and has always gone above and beyond. I was so happy that he received the first DeSalvo Award.” Anderson is the only physics employee to receive the department’s “outstanding service” staff award three times.

Reflecting upon his career, he reports no regrets, but a sense of appreciation. “It’s something to realize that the people you work with are the tops in their fields. It blows you away what people are doing,” Anderson said. “I enjoyed being familiar with the experiments, seeing the ingenuity involved. When you know the intent, helping with the supplying and the setting up and the installation is a thrill.”

Retirement is still a new sensation. Anderson finds the absence of a morning onslaught of anxious emails odd. But he savored not having to face an icy I-95 when snow fell this winter. He enjoys seeing more of his daughter Jessica, who will soon finish her graduate degree in clinical psychology and already works as a social worker, doing home visits to assess children and to assist their parents. He is starting to digitize his vinyl record collection, and will soon enjoy a vacation with Danna to New Orleans. Also planned are trips to see family in Georgia, California and New York. Jesse Anderson and student employee Angela Madden at the 2005 staff awards.

Jesse Anderson and student employee Angela Madden at the 2005 staff awards.

Throughout his 34 years in the department, Anderson was deeply appreciated for his even keel and reassuring demeanor. “We miss Jesse, because he was always such a tremendous person and colleague,” said Rolston. “I can’t recall ever seeing him frazzled or irritated in the least. But he richly deserves an excellent retirement. He did whatever was needed in the department, from filling dewars on the Toll loading dock to hand-delivering important mail. We can’t thank him enough.”

At a staff luncheon in December, Anderson’s colleagues recognized him with a Department of Physics purchase order for a happy and healthy retirement. Anderson expressed his gratitude and drew a laugh when noting, “I’ve spent more time with you than I have with anyone else in my life.” Anderson affirmed that he truly regards the physics department as family, meaning that at UMD he gained two: One begun in a momentous elevator ride, and one established through 34 years of camaraderie.